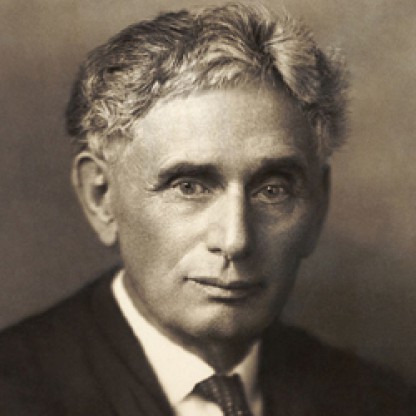

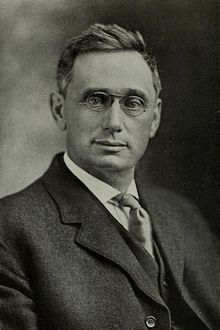

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Former Lawyer & US Supreme Court Associate Justice |

| Birth Day | November 13, 1856 |

| Birth Place | Louisville, Kentucky, United States |

| Age | 163 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | October 5, 1941(1941-10-05) (aged 84)\nWashington, D.C., U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Nominated by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Joseph Lamar |

| Succeeded by | William Douglas |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Goldmark (1891–1941) |

| Education | Harvard University (LLB) |

Net worth

Louis Brandeis, a former lawyer and US Supreme Court Associate Justice, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2024. Brandeis, renowned for his legal expertise and contribution to the American judicial system, served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939. Throughout his career, Brandeis played a pivotal role in landmark decisions, advocating for individual rights, privacy, and democratic principles. His legacy endures as a champion for justice and his financial worth reflects his accomplished legal career and contributions to society.

Famous Quotes:

I believe that only goodness and truth and conduct that is humane and self-sacrificing toward those who need us can bring God nearer to us ... I wanted to give my children the purest spirit and the highest ideals as to morals and love. God has blessed my endeavors.

Biography/Timeline

Louis Dembitz Brandeis was born on November 13, 1856, in Louisville, Kentucky, the youngest of four children. His parents, Adolph Brandeis and Frederika Dembitz, both of whom were Ashkenazi Jews, immigrated to the United States from their childhood homes in Prague, Bohemia (then part of the Austrian Empire). They emigrated as part of their extended families for both economic and political reasons. The Revolutions of 1848 had produced a series of political upheavals and the families, though politically liberal and sympathetic to the rebels, were shocked by the anti-Semitic riots that erupted in Prague while the rebels controlled it. In addition, the Habsburg Empire had imposed Business taxes on Jews. Family elders sent Adolph Brandeis to America to observe and prepare for his family's possible emigration. He spent a few months in the Midwest and was impressed by the nation's institutions and by the tolerance among the people he met. He wrote home to his wife, "America's progress is the triumph of the rights of man."

Louis grew up in "a family enamored with books, music, and politics, perhaps best typified by his revered uncle, Lewis Dembitz, a refined, educated man who served as a delegate to the Republican convention in 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln for President."

In school, Louis was a serious student in languages and other basic courses and usually achieved top scores. Brandeis graduated from the Louisville Male High School at age 14 with the highest honors. When he was sixteen, the Louisville University of the Public Schools awarded him a gold medal for "excellence in all his studies." Anticipating an economic downturn, Adolph Brandeis relocated the family to Europe in 1872. After a period spent traveling, Louis spent two years studying at the Annenschule in Dresden, Saxony, where he excelled. He later credited his capacity for critical thinking and his Desire to study law in the United States to his time there.

Returning to the U.S. in 1875, Brandeis entered Harvard Law School at the age of eighteen. It was his admiration for the wide learning and debating skills of his uncle, Lewis Dembitz, that inspired him to study law. Despite the fact that he entered the school without any financial help from his family, he became "an extraordinary student".

After graduation, he stayed on at Harvard for another year, where he continued to study law on his own while also earning a small income by tutoring other law students. In 1878, he was admitted to the Missouri bar and accepted a job with a law firm in St. Louis, where he filed his first brief and published his first law review article. After seven months, he tired of the minor casework and accepted an offer by his Harvard classmate, Samuel D. Warren, to set up a law firm in Boston. They were close friends at Harvard where Warren ranked second in the class to Brandeis's first. Warren was also the son of a wealthy Boston family and their new firm was able to benefit from his family's connections.

Brandeis's and Warren's firm has been in continuous practice in Boston since its founding in 1879; the firm is known as Nutter McClennen & Fish.

Between 1888 and 1890, Brandeis and his law partner, Samuel Warren, wrote three scholarly articles published in the Harvard Law Review. The third, "The Right to Privacy," was the most important, with legal scholar Roscoe Pound saying it accomplished "nothing less than adding a chapter to our law."

In 1889, Brandeis entered a new phase in his legal career when his partner, Samuel Warren, withdrew from their partnership to take over his recently deceased father's paper company. He then took on cases with the help of colleagues, two of whom became partners in his new firm, Brandeis, Dunbar, and Nutter, in 1897.

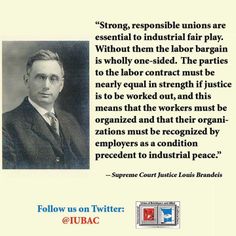

During the 1890s Brandeis began to question his views on American industrialism, write Klebanow and Jonas. He became aware of the growing number of giant companies which were capable of dominating whole industries. He began to lose faith that the economic system was able to regulate them for the public's welfare. As a result, he denounced "cut-throat competition" and worried about monopolies. He also became concerned about the plight of workers and was more sympathetic to the labor movement. His earlier legal battles had convinced him that concentrated economic power could have a negative effect on a free society.

He won his first important victory in 1891, when he persuaded the Massachusetts legislature to make the liquor laws less restrictive and thereby more reasonable and enforceable. He suggested a viable "middle course." By moderating the existing regulations, he told the lawmakers that they would remove liquor dealers' incentive to violate or corrupt the laws. The legislature was won over by his arguments and changed the regulations.

In one of his first such cases, in 1894, he represented Alice N. Lincoln, a Boston philanthropist and noted crusader for the poor. He appeared at public hearings to promote investigations into conditions in the public poor-houses. Lincoln, who had visited these poor-houses for years, saw inmates dwelling in misery and the temporarily unemployed thrown in together with the mentally ill and hardened Criminals. Brandeis spent nine months and held fifty-seven public hearings, at one such hearing proclaiming, "Men are not bad. Men are degraded largely by circumstances....It is the duty of every man...to help them up and let them feel that there is some hope for them in life." As a result of the hearings, the board of aldermen decreed that the administration of the poor law would be completely reorganized.

Brandeis was becoming increasingly conscious of and hostile to powerful corporations and the trend toward bigness in American industry and Finance. He argued that great size conflicted with efficiency and added a new dimension to the Efficiency Movement of the Progressive Era. As early as 1895 he had pointed out the harm that giant corporations could do to competitors, customers, and their own workers. The growth of industrialization was creating mammoth companies which he felt threatened the well-being of millions of Americans. Although the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was enacted in 1890, it was not until the 20th century that there was any major effort to apply it.

In 1896, he was asked to lead the fight against a Boston transit company which was trying to gain concessions from the state legislature that would have given it control over the city's emerging subway system. Brandeis prevailed and the legislature enacted his bill.

Using his social conscience, Brandeis became a leader of the Progressive movement, and used the law as the instrument for social change. From 1897 to 1916, he was in the thick of multiple reform crusades. He fought in Boston to secure honest traction franchises and in 1907 launched a six-year fight to prevent banker J. P. Morgan from monopolizing New England's railroads. After an exposé of insurance fraud in 1906, he devised the Massachusetts plan to protect small wage-earners through savings bank life insurance. He supported the conservation movement and in 1910 emerged as the chief figure in the Pinchot-Ballinger investigation.

The transit franchise struggle revealed that many of Boston's politicians had placed political friends on the payrolls of the private transit companies. One alderman gave jobs to 200 of his followers. In Boston and other cities, such abuses were part of the corruption in which graft and bribery were commonplace, in some cases even newly freed prison felons resumed their political careers. "Always the moralist," writes biographer Thomas Mason, "Brandeis declared that 'misgovernment in Boston had reached the danger point.'" He declared that from then on he would keep a record of good and bad political deeds which would be open to all Boston voters. In one of his public addresses in 1903, he stated his goal:

In March 1905, he became counsel to a New England policyholder's committee which was concerned that their scandal-ridden insurance company would file bankruptcy and the policyholders would lose their Investments and insurance protection. He served without pay so he could be free to address the wider issues involved.

He spent the next year studying the workings of the life insurance industry, often writing articles and giving speeches about his findings, at one point describing their practices as "legalized robbery." By 1906 he concluded that life insurance was a "bad bargain for the vast majority of policyholders," due mostly to the inefficiency of the industry. He also learned that a little understood clause in the policies of low wage workers allowed the policy to be canceled when they missed a payment, and that most policies lapsed, so only one out of eight policyholders received benefits. This led to large profits for insurance companies.

Widely known as "the people's attorney," Brandeis pioneered pro bono work and was a true reformer. Brandeis was also the first to cite law reviews both in his briefs before the court and in his opinions as a justice. In 1907, he pioneered a new type of legal document, the "Brandeis brief." It included three pages of traditional legal citations and over one hundred innovative pages of citations to articles, government reports, and other references. It was packed full of social research and data to demonstrate the public interest in a ten-hour limitation on women's working hours. His brief proved decisive in Muller v. Oregon, which was the first Supreme Court ruling that accepted the legitimacy of a scientific examination of the social conditions in addition to the legal facts involved in a case.

In 1908 he chose to represent the state of Oregon in the case of Muller v. Oregon, to the U.S. Supreme Court. At issue was whether it was constitutional for a state law to limit the hours that female workers could work. Up until this time it was considered an "unreasonable infringement of freedom of contract" between employers and their employees for a state to set any wages or hours legislation.

By 1910 Brandeis noticed that even America's leadership, including President Theodore Roosevelt, were beginning to question the value of antitrust policies. Some Business experts felt that nothing could prevent the concentration of industry and therefore big Business was here to stay. As a result, Leaders like Roosevelt began to "regulate," but not limit, the growth and operation of corporate monopolies, although Brandeis wanted the trend to bigness slowed or even reversed. He was convinced that monopolies and trusts were "neither inevitable nor desirable." In support of Brandeis's position were presidential candidate william Jennings Bryan and Robert M. La Follette Sr., senator from Wisconsin.

Part of his reasoning and philosophy for acting as a public advocate he later explained in his 1911 book, The Opportunity in the Law:

He also urged the Wilson administration to develop proposals for new antitrust legislation to give the Department of Justice the power to enforce antitrust laws, with Brandeis becoming one of the Architects of the Federal Trade Commission. Brandeis also served as Wilson's chief economic adviser from 1912 until 1916. "Above all else," writes McCraw, "Brandeis exemplified the anti-bigness ethic without which there would have been no Sherman Act, no antitrust movement, and no Federal Trade Commission."

In 1913, Brandeis wrote a series of articles for Harper's Weekly that suggested ways of curbing the power of large banks and money trusts. And in 1914 he published a book entitled Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It.

Relatively late in life the secular Brandeis also became a prominent figure in the Zionist movement. He became active in the Federation of American Zionists in 1912, as a result of a conversation with Jacob de Haas, according to some. His involvement provided the nascent American Zionist movement one of the most distinguished men in American life and a friend of the next President. Over the next several years he devoted a great deal of his time, Energy, and money to championing the cause. With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the divided allegiance of its membership rendered the World Zionist Organization impotent. American Jews then assumed a larger responsibility independent of Zionists in Europe. The Provisional Executive Committee for Zionist Affairs was established in New York for this purpose on August 20, 1914, and Brandeis was elected President of the organization. As President from 1914 to 1918, Brandeis became the leader and spokesperson of American Zionism. He embarked on a speaking tour in the fall and winter of 1914–1915 to garner support for the Zionist cause, emphasizing the goal of self-determination and freedom for Jews through the development of a Jewish homeland.

Early in the war, Jewish Leaders determined that they needed to elect a special representative body to attend the peace conference as spokesman for the religious, national and political rights of Jews in certain European countries, especially to guarantee that Jewish minorities were included wherever minority rights were recognized. Under the leadership of Brandeis, Stephen Wise and Julian Mack, the Jewish Congress Organization Committee was established in March 1915. The subsequent vehement debate about the idea of a "congress" stirred the feelings of American Jews and acquainted them with the Jewish Problem. Brandeis' efforts to bring in the American Jewish Committee and some other Jewish organizations were unsuccessful; these organizations were quite willing to participate in a conference of appointed representatives, but were opposed to Brandeis's idea of convening a congress of delegates elected by the Jewish population.

A month later, on June 1, 1916, the Senate officially confirmed his nomination by a vote of 47 to 22. Forty-four Democratic Senators and three Republicans (Robert La Follette, George Norris, and Miles Poindexter) voted in favor of confirming Brandeis. Twenty-one Republican Senators and one Democrat (Francis G. Newlands) voted against his confirmation.

The following year, however, delegates representing over one million Jews came together in Philadelphia and elected a National Executive Committee with Brandeis as honorary chairman. On April 6, 1917, America entered the war. On June 10, 1917, 335,000 American Jews cast their votes and elected their delegates who, together with representatives of some 30 national organizations, established the American Jewish Congress on a democratically elected basis, but further efforts to organize awaited the end of the war.

Later in 1919 Brandeis broke with Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the European Zionism. In 1921 Weizmann's candidates, headed by Louis Lipsky, defeated Brandeis's for political control of the Zionist Organization of America. Brandeis resigned from the ZOA, along with his closest associates Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Judge Julian W. Mack and Felix Frankfurter. His ouster was devastating to the movement, and by 1929 there were no more than 18,000 members in the ZOA. Nonetheless he remained active in philanthropy directed at Jews in Palestine. In the summer of 1930, these two factions and visions of Zionism, would come to a compromise largely on Brandeis's terms, with a changed leadership structure for the ZOA. In the late 1930s he endorsed immigration to Palestine in an effort to help European Jews escape genocide when Britain denied entry to more Jews.

One such case was Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920) which dealt with a state law prohibiting interference with the military's enlistment efforts. In his dissenting opinion, Brandeis wrote that the statute affected the "rights, privileges, and immunities of one who is a citizen of the United States; and it deprives him of an important part of his liberty. ... [T]he statute invades the privacy and freedom of the home. Father and mother may not follow the promptings of religious belief, of conscience or of conviction, and teach son or daughter the doctrine of pacifism. If they do, any police officer may summarily arrest them."

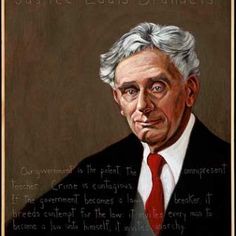

In his widely cited dissenting opinion in Olmstead v. United States (1928), Brandeis relied on thoughts he developed in his 1890 Harvard Law Review article "The Right to Privacy." But in his dissent, he now changed the focus whereby he urged making personal privacy matters more relevant to constitutional law, going so far as saying "the government [was] identified ... as a potential privacy invader." At issue in Olmstead was the use of wiretap Technology to gather evidence. Referring to this "dirty Business," he then tried to combine the notions of civil privacy and the "right to be let alone" with the right offered by the Fourth Amendment which disallowed unreasonable search and seizure. Brandeis wrote in his lengthy dissent:

In Packer Corporation v. Utah (1932), Brandeis was to advance an exception to the right of free speech. In this case, a unanimous Court, led by Brandeis, found a clear distinction between advertising placed in newspapers and magazines with those placed on public billboards. The case was a notable exception and dealt with a conflict between widespread First Amendment rights with the public's right of privacy and advanced a theory of the "captive audience." Brandeis delivered the opinion of the Court to advance privacy interests:

In 1934, Brandeis had another legal confrontation with The House of Morgan, this one relating to securities regulation bills. J. P. Morgan's resident Economist, Russell Leffingwell, felt it necessary to remind their banker, Tom Lamont, whom they would be dealing with:

In Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), the Court also voted unanimously to declare the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) unconstitutional on the grounds that it gave the President "unfettered discretion" to make whatever laws he thought were needed for economic recovery. Economics author John Steele Gordon writes that the National Recovery Administration (NRA) was "the first iteration of Roosevelt's New Deal ... essentially a government-run cartel to fix prices and divide markets ... This was the most radical shift in the relation between government and the private economy in American history." Speaking to aides of Roosevelt, Justice Louis Brandeis remarked that, "This is the end of this Business of centralization, and I want you to go back and tell the President that we're not going to let this government centralize everything."

Brandeis also opposed Roosevelt's court-packing scheme of 1937, which proposed to add one additional justice to the Supreme Court for every sitting member who had reached the age of seventy without retiring. "This was," felt Brandeis and others on the Court, a "thinly veiled attempt to change the decisions of the Court by adding new members who were supporters of the New Deal," leading Historian Nelson Dawson to conclude that "Brandeis ... was not alone in thinking that Roosevelt's scheme threatened the integrity of the institution."

His last important judicial opinion was also one of the most significant of his career, according to Klebanow and Jonas. In Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938), the Supreme Court addressed the issue of whether federal judges apply state law or federal "general law" where the parties to a lawsuit are from different states. Writing for the Court, Brandeis overruled the ninety-six-year-old doctrine of Swift v. Tyson (1842), and held that there was no such thing as a "federal general Common law" in cases involving diversity jurisdiction. This concept became known as the Erie Doctrine. Applying the Erie Doctrine, federal courts now must conduct a choice of law analysis, which generally requires that the courts apply the law of the state where the injury or transaction occurred. "This ruling," concluded Klebanow and Jonas, "fits in well with Brandeis's goals of strengthening the states and reversing the long-term trend toward centralization and bigness."

Brandeis retired from the Supreme Court on February 13, 1939, and he died on October 5, 1941, following a heart attack.

In succeeding years his right of privacy concepts gained powerful disciples who relied on his dissenting opinion: Justice Frank Murphy, in 1942, used his Harvard Law Review article in writing an opinion for the Court; a few years later, Justice Felix Frankfurter referred to the Fourth Amendment as the "protection of the right to be let alone," as in the 1947 case of United States v. Harris, where his opinion wove together the speeches of James Otis, James Madison, John Adams, and Brandeis's Olmstead opinion, proclaiming the right of privacy as "second to none in the Bill of Rights

It took the growth of surveillance Technology during the 1950s and 1960s and the "full force of the Warren Court's due process revolution," writes McIntosh, to finally overturn the Olmstead law: in 1967, Justice Potter Stewart wrote the opinion overturning Olmstead in Katz v. U.S. McIntosh adds, "A quarter-century after his death, another component of Justice Brandeis's privacy design was enshrined in American law."

One of the hallmarks of the case was Brandeis's minimizing common-law jurisprudence in favor of extralegal information relevant to the case. According to judicial Historian Stephen Powers, the "so-called 'Brandeis Brief' became a model for progressive litigation," by taking into consideration social and historical realities rather than just the abstract general principles. He adds that it had "a profound impact on the Future of the legal profession" by accepting more broad-based legal information. John Vile adds that this new "Brandeis Brief" was increasingly used, most notably in the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954 that desegregated public schools.

Legal author Ken Gormley says Brandeis was "attempting to introduce a notion of privacy which was connected in some fashion to the Constitution...and which worked in tandem with the First Amendment to assure a freedom of speech within the four brick walls of the citizen's residence." In 1969, in Stanley v. Georgia, Justice Marshall succeeded in linking the right of privacy with freedom of speech and making it part of the constitutional structure, quoting from Brandeis's Olmstead dissent and his Whitney concurrence, and adding his own conclusions from the case at hand, which dealt with the issue of viewing pornography at home:

The U.S. Postal Service in September 2009 honored Brandeis by featuring his image on a new set of commemorative stamps along with U.S. Supreme Court associate justices Joseph Story, Felix Frankfurter and william J. Brennan Jr. In the Postal Service announcement about the stamp, he was credited with being "the associate justice most responsible for helping the Supreme Court shape the tools it needed to interpret the Constitution in light of the sociological and economic conditions of the 20th century." The Postal Service honored him with a stamp image in part because, their announcement states, he was "a progressive and champion of reform, [and] Brandeis devoted his life to social justice. He defended the right of every citizen to speak freely, and his groundbreaking conception of the right to privacy continues to impact legal thought today."

Wayne McIntosh writes of him, "In our national juristic temple, some figures have been accorded near-Olympian reverence... a part of that legal pantheon is Louis D. Brandeis – all the more so, perhaps because Brandeis was far more than a great justice. He was also a social reformer, legal innovator, labor champion, and Zionist leader... And it was as a judge that his concepts of privacy and free speech ultimately, if posthumously, resulted in virtual legal sea changes that continue to resonate even today." Former Justice william O. Douglas wrote, "he helped America grow to greatness by the dedications of which he made his life."

Along with Benjamin Cardozo and Harlan F. Stone, Brandeis was considered to be in the liberal wing of the court—the so-called Three Musketeers who stood against the conservative Four Horsemen.

Among Brandeis's key themes was the conflict he saw between 19th-century values, with its culture of the small Producer, and an emerging 20th-century age of big Business and consumerist mass society. Brandeis was hostile to the new consumerism. Though himself a millionaire, Brandeis disliked wealthy persons who engaged in conspicuous consumption or were ostentatious. He did little shopping himself, and unlike his wealthy friends who owned yachts, he was satisfied with his canoe.