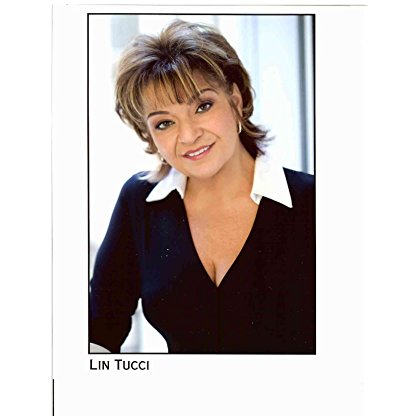

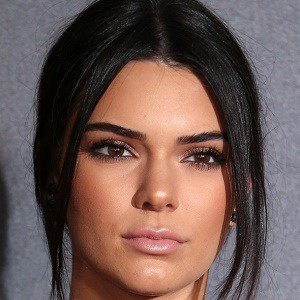

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actress, Editorial Department, Producer |

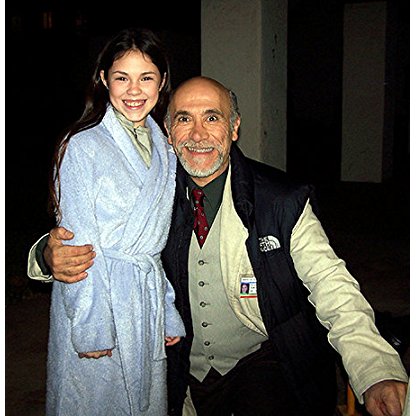

| Birth Day | October 19, 2005 |

| Birth Place | Burbank, California, United States |

| Age | 18 YEARS OLD |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

Net worth

Marina Anderson, a multi-talented individual in the entertainment industry, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M by the year 2024. Hailing from the United States, Marina is renowned for her contributions not only as an actress but also as an editorial department member and a producer. With her diverse skill set and passion for the arts, she has managed to carve a successful career in the competitive realm of Hollywood. As she continues to excel in her various roles, her net worth is projected to grow steadily, further solidifying her position as a notable figure in the industry.

Biography/Timeline

Marian Anderson was born on February 27, 1897, in Philadelphia, the daughter of John Berkley Anderson and the former Annie Delilah Rucker. Her father sold ice and coal at the Reading Terminal in downtown Philadelphia and eventually opened a small liquor Business as well. Prior to her marriage, Anderson's mother had briefly attended the Virginia Seminary and College in Lynchburg and had worked as a schoolteacher in Virginia. As she did not obtain a degree, Annie Anderson was unable to teach in Philadelphia under a law that was applied only to black teachers and not white ones. She therefore earned an income caring for small children. Marian was the eldest of the three Anderson children. Her two sisters, Alice (later spelled Alyse) (1899–1965) and Ethel (1902–1990), also became Singers. Ethel married James DePreist and their late son, James Anderson DePreist was a noted Conductor.

When Anderson was 12, her father was accidentally struck on the head while at work at the Reading Terminal, just a few weeks before Christmas of 1909. He died of heart failure a month later at age 34. Marian and her family moved into the home of her father's parents, Grandpa Benjamin and Grandma Isabella Anderson. Her grandfather had been born a slave and had experienced emancipation in the 1860s. He was the first of the Anderson family to settle in South Philadelphia, and when Anderson moved into his home the two became very close. He died just a year after the family moved in.

Anderson attended Stanton Grammar School, graduating in the summer of 1912. Her family, however, could not afford to send her to high school, nor could they pay for any music lessons. Still, Anderson continued to perform wherever she could and learn from anyone who was willing to teach her. Throughout her teenage years, she remained active in her church's musical activities, now heavily involved in the adult choir. She joined the Baptists' Young People's Union and the Camp Fire Girls which provided her with some limited musical opportunities. Eventually the Directors of the People's Chorus and the pastor of her church, Reverend Wesley Parks, along with other Leaders of the black community, raised the money she needed to get singing lessons with Mary Saunders Patterson and to attend South Philadelphia High School, from which she graduated in 1921.

After high school, Anderson applied to an all-white music school, the Philadelphia Music Academy (now University of the Arts), but was turned away because she was black. The woman working the admissions counter replied, "We don't take colored" when she tried to apply. Undaunted, Anderson pursued studies privately in her native city through the continued support of the Philadelphia black community, first with Agnes Reifsnyder, then Giuseppe Boghetti. She met Boghetti through the principal of her high school. Anderson auditioned for him singing 'Deep River' and he was immediately brought to tears. In 1925 Anderson got her first big break when she won first prize in a singing competition sponsored by the New York Philharmonic. As the winner she got to perform in concert with the orchestra on August 26, 1925, a performance that scored immediate success with both audience and music critics. Anderson remained in New York to pursue further studies with Frank La Forge. During the time Arthur Judson, whom she had met through the NYP, became her manager. Over the next several years, she made a number of concert appearances in the United States, but racial prejudice prevented her career from gaining much momentum. In 1928, she sang for the first time at Carnegie Hall. Eventually she decided to go to Europe where she spent a number of months studying with Sara Charles-Cahier before launching a highly successful European singing tour.

In the late 1930s, Anderson gave about 70 recitals a year in the United States. Although by then quite famous, her stature did not completely end the prejudice she confronted as a young black singer touring the United States. She was still denied rooms in certain American hotels and was not allowed to eat in certain American restaurants. Because of this discrimination, Albert Einstein, a champion of racial tolerance, hosted Anderson on many occasions, the first being in 1937 when she was denied a hotel before performing at Princeton University. She last stayed with him months before he died in 1955.

In 1933, Anderson made her European debut in a concert at Wigmore Hall in London, where she was received enthusiastically. She spent the early 1930s touring throughout Europe where she did not encounter the racial prejudices she had experienced in America. In the summer of 1930, she went to Scandinavia, where she met the Finnish Pianist Kosti Vehanen who became her regular accompanist and her vocal coach for many years. She also met Jean Sibelius through Vehanen after he had heard her in a concert in Helsinki. Moved by her performance, Sibelius invited them to his home and asked his wife to bring champagne in place of the traditional coffee. Sibelius commented to Anderson of her performance that he felt that she had been able to penetrate the Nordic soul. The two struck up an immediate friendship, which further blossomed into a professional partnership, and for many years Sibelius altered and composed songs for Anderson to perform. He created a new arrangement of the song "Solitude" and dedicated it to Anderson in 1939. Originally The Jewish Girl's Song from his 1906 incidental music to Belshazzar's Feast, it later became the "Solitude" section of the orchestral suite derived from the incidental music.

In 1934, impresario Sol Hurok offered Anderson a better contract than she previously had with Arthur Judson. He became her manager for the rest of her performing career and through his persuasion she came back to perform in America. In 1935, Anderson made her first recital appearance in New York at Town Hall, which received highly favorable reviews by music critics. She spent the next four years touring throughout the United States and Europe. She was offered opera roles by several European houses but, due to her lack of acting experience, Anderson declined all of those offers. She did, however, record a number of opera arias in the studio, which became bestsellers.

From 1940 she resided at a 50-acre farm, having sold half of the original 100 acres, that she named Marianna Farm. The farm was on Joe's Hill Road, in the Mill Plain section of Danbury in western Danbury, North West of what in December 1961 became the interchange between Interstate 84, U.S. 6 and U.S. 202. She constructed a three-bedroom ranchhouse as a residence, and she used a separate one-room structure as her studio. In 1996, the farm was named one of 60 sites on the Connecticut Freedom Trail. The studio was moved to downtown Danbury as the Marian Anderson studio.

The Marian Anderson Award was originally established in 1943 by Anderson after she was awarded the $10,000 Bok Prize that year by the city of Philadelphia. Anderson used the award money to establish a singing competition to help support young Singers. Eventually the prize fund ran out of money and it was disbanded after 1976. In 1990, the award was re-established and has dispensed $25,000 annually.

On January 7, 1955, Anderson became the first African-American to perform with the Metropolitan Opera in New York. On that occasion, she sang the part of Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi's Un ballo in maschera (opposite Zinka Milanov, then Herva Nelli, as Amelia) at the invitation of Director Rudolf Bing. Anderson said later about the evening, "The curtain rose on the second scene and I was there on stage, mixing the witch's brew. I trembled, and when the audience applauded and applauded before I could sing a note, I felt myself tightening into a knot." Although she never appeared with the company again after this production, Anderson was named a permanent member of the Metropolitan Opera company. The following year she published her autobiography, My Lord, What a Morning, which became a bestseller.

In 1957, she sang for President Dwight D. Eisenhower's inauguration, toured India and the Far East as a goodwill ambassadress through the U.S. State Department and the American National Theater and Academy. She traveled 35,000 miles (56,000 km) in 12 weeks, giving 24 concerts. After that, President Eisenhower appointed her as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The same year, she was elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1958 she was officially designated delegate to the United Nations, a formalization of her role as "goodwill ambassadress" of the U.S. which she had played earlier.

Anderson worked for several years as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and as a "goodwill ambassadress" for the United States Department of State, giving concerts all over the world. She participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, singing at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The recipient of numerous awards and honors, Anderson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, the Congressional Gold Medal in 1977, the Kennedy Center Honors in 1978, the National Medal of Arts in 1986, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

On January 20, 1961 she sang for President John F. Kennedy's inauguration, and in 1962 she performed for President Kennedy and other dignitaries in the East Room of the White House, and also toured Australia. She was active in supporting the civil rights movement during the 1960s, giving benefit concerts for the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the America-Israel Cultural Foundation. In 1963, she sang at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. That same year she was one of the original 31 recipients of the newly reinstituted Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is awarded for "especially meritorious contributions to the security or national interest of the United States, World Peace or cultural or other significant public or private endeavors". She also released her album, Snoopycat: The Adventures of Marian Anderson's Cat Snoopy, which included short stories and songs about her beloved black cat. In 1965, she christened the nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarine, USS George Washington Carver. That same year Anderson concluded her farewell tour, after which she retired from public performance. The international tour began at Constitution Hall on Saturday October 24, 1964, and ended at Carnegie Hall on April 18, 1965.

Although Anderson retired from singing in 1965, she continued to appear publicly. On several occasions she narrated Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait, including a performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra at Saratoga in 1976, conducted by the Composer. Her achievements were recognized and honored with many prizes, including the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in 1939; University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit in 1973; the United Nations Peace Prize, New York City's Handel Medallion, and the Congressional Gold Medal, all in 1977; Kennedy Center Honors in 1978; the George Peabody Medal in 1981; the National Medal of Arts in 1986; and a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1991. In 1980, the United States Treasury Department coined a half-ounce gold commemorative medal with her likeness, and in 1984 she was the first recipient of the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award of the City of New York. She has been awarded honorary doctoral degrees from Howard University, Temple University and Smith College.

In 1986, Anderson's husband, Orpheus Fisher, died after 43 years of marriage. Anderson remained in residence at Marianna Farm until 1992, one year before her death. Although the property was sold to developers, various preservationists as well as the City of Danbury fought to protect Anderson's studio. Their efforts proved successful and the Danbury Museum and Historical Society received a grant from the State of Connecticut, relocated the structure, restored it, and opened it to the public in 2004. In addition to seeing the studio, visitors can see photographs and memorabilia from milestones in Anderson's career.

Anderson died of congestive heart failure on April 8, 1993, at age 96. She had suffered a stroke a month earlier. She died in Portland, Oregon, at the home of her nephew, Conductor James DePreist, where she had relocated the year prior. She is interred at Eden Cemetery, in Collingdale, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia.

The life and art of Marian Anderson has inspired several Writers and artists. She was an Example and an inspiration to both Leontyne Price and Jessye Norman. In 1999 a one-act musical play entitled My Lord, What a Morning: The Marian Anderson Story was produced by the Kennedy Center. The musical took its title from Anderson's memoir, published by Viking in 1956. In 2001, the 1939 documentary film, Marian Anderson: the Lincoln Memorial Concert was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Marian Anderson in his book, 100 Greatest African Americans. On January 27, 2006, a commemorative U.S. postage stamp honored Marian Anderson as part of the Black Heritage series. Anderson is also pictured on the US$5,000 Series I United States Savings Bond. On April 20, 2016, United States Secretary of the Treasury, Jacob Lew, announced that Marian Anderson will appear along with Eleanor Roosevelt and suffragettes on the back of the redesigned US $5 bill scheduled to be unveiled in the year 2020, the 100th anniversary of 19th Amendment of the Constitution which granted women in America the right to vote.

The Marian Anderson House, in Philadelphia, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.