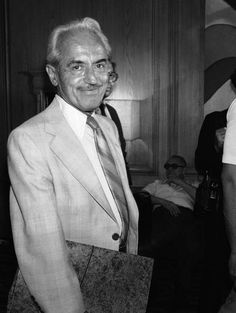

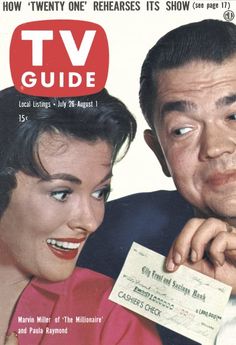

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actor, Miscellaneous Crew |

| Birth Day | April 14, 1917 |

| Birth Place | St. Louis, Missouri, United States |

| Age | 103 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 27, 2012(2012-11-27) (aged 95)\nManhattan, New York City, New York, US |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Occupation | Executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association (1966–1982) |

| Spouse(s) | Theresa Morgenstern |

| Children | 2 |

Net worth: $100K - $1M

Famous Quotes:

"I find myself unwilling to contemplate one more rigged Veterans Committee whose members are handpicked to reach a particular outcome while offering a pretense of a democratic vote. It is an insult to baseball fans, historians, sportswriters, and especially to those baseball players who sacrificed and brought the game into the 21st century. At the age of 91, I can do without farce."

Biography/Timeline

Miller was born in The Bronx on April 14, 1917, and grew up in Flatbush, Brooklyn, rooting for the Brooklyn Dodgers. His father, Alexander, was a salesman for a clothing company on the Lower East Side in Manhattan; and, as a youngster, Marvin walked a picket line in a union organizing drive. His mother, Gertrude Wald Miller, who taught elementary school, was a member of the New York City teachers union, now the United Federation of Teachers.

Miller graduated from New York University in 1938 with a degree in Economics. He resolved labor-management disputes for the National War Labor Board in World War II and later worked for the International Association of Machinists and the United Auto Workers. He joined the staff of the United Steelworkers in 1950, became its principal economic adviser and assistant to its President, and took part in negotiating contracts.

During Miller's tenure as the Executive Director of the MLBPA, the average player's annual salary rose from $19,000 in 1966 to $326,000 in 1982. Miller taught MLB players the basics of human capital as a commodity they were selling to club owners. Working with MLBPA general counsel, Richard M. Moss, Miller educated the players to trade-union thinking. Moss was one of Miller's most trusted advisors at the MLBPA. Richard M. Moss later went on to become a MLB agent. The 1968 collective bargaining agreement was the first of its kind in pro Sports. In 1970, players gained the right to have grievances heard by an impartial arbitrator. In 1973, they achieved a limited right to have salary demands subjected to arbitration.

Miller negotiated MLBPA's first collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with the team owners in 1968. That CBA, covering the 1968 and 1969 seasons, was a short document. It won the players a nearly 43 percent increase in the minimum salary from $7,000 to $10,000, as well as larger expense allowances. More importantly, the deal brought a formal structure to owner–player relations, including written procedures for the arbitration of player grievances before the commissioner.

Throughout the 1969 season, Curt Flood, a perennial standout player for the powerhouse St. Louis Cardinals, argued with Cardinals owner August Busch and General Manager Bing Devine over a $10,000 raise in his $90,000 salary. Shortly after the 1969 season concluded, Devine sent Flood a terse, two sentence letter notifying him that he had been traded to the then National League East cellar dwelling Philadelphia Phillies. Flood took the trade as an insult and also viewed it as a punishment by Cardinals management for his increased salary demands. Philadelphia's Shibe Park was known to be the most dilapidated in the major leagues compared with Busch Stadium that opened in 1966. Worse still, Phillies fans had earned a reputation for being virulent racists as was evidenced by the epithets and garbage they hurled at black player Dick Allen. (So bad was Allen's treatment at the hands of Phillies fans, he took to wearing a batting helmet while playing in the field.) Coincidentally, Allen was the player the "Phils" sent to St. Louis as its part of the bargain for Flood.

Flood wrote a letter to then Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn stating that he did not view himself as "property" and instructed Kuhn to notify all teams in Major League Baseball that he was willing to consider financial offers to play for any team during the 1970 season. Flood had chosen to ignore the age old reserve clause, which prevented him from negotiating with any MLB team until he had sat out a season. Flood did not take his challenge of the reserve clause lightly and did consult with Miller before suing MLB and Bowie Kuhn. "I told him," recalled Miller, "that given the courts' history of bias towards the owners and their monopoly, he didn't have a chance in hell of winning. More important than that, I (Miller) told him even if he won, he'd never get anything out of it—he'd never get a job in baseball again." Flood asked Miller if it would benefit other players. "I (Miller) told him yes, and those to come."

Meanwhile, Miller took his union on a "lightning" strike on April Fools Day 1972. From April 1 through April 13, the ballplayers simply stayed away from the ballparks while Miller negotiated with the owners. Baseball only resumed when the owners and players agreed on a $500,000 increase in pension fund payments. Owners agreed to add salary arbitration to the CBA. The total 86 exhibition and regular season games that were missed over the entire 13-day period were never played because the league refused to pay the players for the time they were on strike. Most teams lost anywhere from six to eight games off their 162-game schedule.

In 1974, Miller encouraged two other pitchers Andy Messersmith of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Dave McNally of the Baltimore Orioles to play out the succeeding year without signing a contract. After the year had elapsed, both players filed a grievance arbitration. The ensuing Seitz decision declared that both players had fulfilled their contractual obligations and had no further legal ties to their ballclubs. This effectively eradicated the reserve clause and ushered in free agency. As an Economist, Miller clearly understood that too many free agents could actually drive down player salaries. Miller agreed to limit free agency to players with more than six years of Service, hoping that restricting the supply of labor would drive up salaries as owners bid for an annual, finite pool of free agents. Miller's hopes were frustrated for a time as baseball owners engaged in collusion in which they agreed among themselves not to deal with any player who was a free agent.

Miller led the ballplayer's union in two more actions against the Major League owners, the second during 1980 spring training, and the third during the heart of the 1981 regular season. The 1981 strike, which lasted 50 days, forced the total cancellation of 713 games, and is estimated to have cost both the owners and players $146 million. Under Marvin Miller's 16-year tenure as the Executive Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, the owners engaged in two lockouts, one in 1973 spring training and the other in 1976 spring training, both the result of negotiations for collective bargaining agreements.

Marvin Miller was succeeded in 1985 by Donald Fehr, who had joined the Major League Baseball Players Association as general counsel in 1977. Miller, even after retiring, remained close with his successor as a consultant. Fehr stepped down in 2009 and was replaced by the union's general counsel, Michael Weiner.

In 1997, the MLB Players Association created the Marvin Miller Man of the Year Award as one of its annual "Players Choice Awards".

On April 1, 2000, he was honored by the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.

MLB is the only professional sport in the U.S. not to have a salary cap. (Although a competitive balance tax has been implemented since 2002, whereby any teams that exceed a mutually agreed upon amount in total salaries are assessed the tax which is paid to MLB and put in an industry growth fund to keep the sport competitive.)

Miller fell short of selection to the Baseball Hall of Fame in both 2003 and 2007, although he finished among the leading candidates in voting for executives with 63%. (Election requires 75% of the vote.) The 2003 and 2007 votes had been conducted among a committee of all living Hall of Famers, who are primarily players. After they failed to agree on any candidate, including Miller, the voting body was reduced to 12 members, ten of them non-playing. CNNMoney Writer Chris Isidore described the switch's effect on Miller's candidacy: "Imagine a Runner rounding third and heading for home, only to have a last minute rule change move the location of the plate. That's roughly what happened to Marvin Miller's chances of getting his long overdue recognition in baseball's Hall of Fame." Miller was up for election again in 2007 under a revamped voting format, but received only 3 of the necessary 9 votes.

Asked to predict his chances before the 2007 results had been announced, Miller said, "Let me point out one thing. In the last vote, the number of management people among the voters was a certain percentage. On the new committee management is completely dominant. Aside from miracles, there's no reason to believe the vote will do anything but go down." On another occasion, Miller laughed, "I've never prepared an acceptance speech."

On July 11, 2008, the Boston Globe portrayed Miller as disdainful of the realignment of the Hall's Veterans Committee, and as uninterested in the chances of his own enshrinement. From the article, Miller was quoted:

On April 26, 2009, he was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.

Further changes were made to the Veterans Committee voting process in 2010, effective with the 2011 induction cycle. Miller was named as one of 12 figures from what the Hall calls the "Expansion Era" (1973–present) to be considered. The composition of the new 16-man voting committee was very different from that in 2007, consisting of eight Hall of Famers (seven inducted as players and one as a manager), four media members, and only four executives. Despite the changes, Miller again missed out on election, this time falling one vote short of induction.

Miller was diagnosed with liver cancer in August 2012. He died on November 27, 2012, at the age of 95, in his home in Manhattan. In a statement, Michael Weiner, the executive Director of the MLBPA, said: "It is with profound sorrow that we announce the passing of Marvin Miller. All players – past, present and Future – owe a debt of gratitude to Marvin, and his influence transcends baseball. Marvin, without question, is largely responsible for ushering in the modern era of Sports, which has resulted in tremendous benefits to players, owners and fans of all Sports."

The Supreme Court decided against Flood by a 5–3–1 vote in June 1972. Flood sat out the 1970 season because no owner wanted to set a precedent by flagrantly disobeying the reserve clause. In 1971 he was signed by and played just 13 lackluster games for the Washington Senators. After that, a disgusted Flood never played Major League Baseball again. Twenty years later, Miller wrote in his memoir that Flood told the players union, "I think the change in black consciousness in recent years has made me more sensitive to injustice in every area of my life." Miller also said that Flood was primarily challenging the reserve clause as a professional ballplayer.

Miller was on the Expansion Era ballot for the 2014 class, but received fewer than 6 of 16 votes and was not selected for induction.Miller again fell short in the 2017 Modern Baseball Era Committee balloting, receiving only 7 of the 12 votes necessary for election. He will eligible again in 2019.