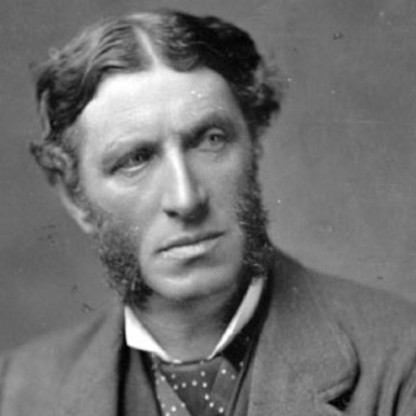

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Poet |

| Birth Day | December 24, 1822 |

| Birth Place | Laleham, United Kingdom, British |

| Age | 197 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 15 April 1888 (1888-04-16) (aged 65)\nLiverpool, England |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Occupation | Her Majesty's Inspector of Schools |

| Period | Victorian |

| Genre | Poetry; literary, social and religious criticism |

| Notable works | "Dover Beach", "The Scholar-Gipsy", "Thyrsis", Culture and Anarchy, Literature and Dogma |

| Spouse | Frances Lucy |

| Children | Thomas Trevenen Richard Lucy Eleanore Basil |

Net worth: $400,000 (2024)

Matthew Arnold, known as a distinguished poet in British literature, is projected to have a net worth of approximately $400,000 by the year 2024. Arnold, an influential figure in the Victorian era, made significant contributions to English poetry and literary criticism. His insightful writings, such as "Dover Beach" and "Culture and Anarchy," explored profound themes of change, spirituality, and societal upheaval. Despite his dedication to the arts, Arnold's modest net worth reflects the challenging financial realities often faced by poets during his time, emphasizing the common struggle between artistic pursuit and financial stability. However, his invaluable contributions continue to shape the literary landscape, solidifying Matthew Arnold's legacy as a revered poet in British history.

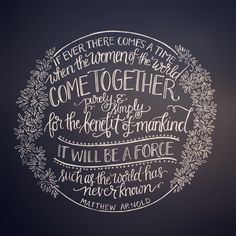

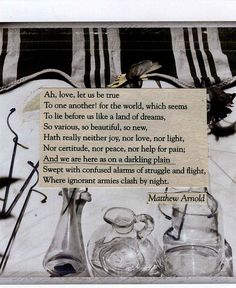

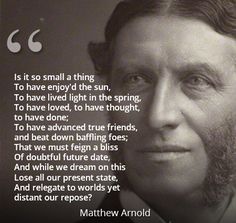

Famous Quotes:

My poems represent, on the whole, the main movement of mind of the last quarter of a century, and thus they will probably have their day as people become conscious to themselves of what that movement of mind is, and interested in the literary productions which reflect it. It might be fairly urged that I have less poetical sentiment than Tennyson and less intellectual vigour and abundance than Browning; yet because I have perhaps more of a fusion of the two than either of them, and have more regularly applied that fusion to the main line of modern development, I am likely enough to have my turn as they have had theirs."

Biography/Timeline

The Reverend John Keble, who would become one of the Leaders of the Oxford Movement, stood as godfather to Matthew. "Thomas Arnold admired Keble's 'hymns' in The Christian Year, only reversing himself with exasperation when this old friend became a Romeward-tending 'High Church' reactionary in the 1830s." In 1828, Arnold's father was appointed Headmaster of Rugby School and his young family took up residence, that year, in the Headmaster's house. In 1831, Arnold was tutored by his uncle, Rev. John Buckland in the small village of Laleham. In 1834, the Arnolds occupied a holiday home, Fox How, in the Lake District. william Wordsworth was a neighbour and close friend. In 1836, Arnold was sent to Winchester College, but in 1837 he returned to Rugby School where he was enrolled in the fifth form. He moved to the sixth form in 1838 and thus came under the direct tutelage of his father. He wrote verse for the manuscript Fox How Magazine co-produced with his brother Tom for the family's enjoyment from 1838 to 1843. During his years there, he won school prizes for English essay writing, and Latin and English poetry. His prize poem, "Alaric at Rome," was printed at Rugby.

In 1841, he won an open scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. During his residence at Oxford, his friendship ripened with Arthur Hugh Clough, another Rugby old boy who had been one of his father's favourites. Arnold attended John Henry Newman's sermons at St. Mary's but did not join the Oxford Movement. His father died suddenly of heart disease in 1842, and Fox How became his family's permanent residence. Arnold's poem Cromwell won the 1843 Newdigate prize. He graduated in the following year with a 2nd class honours degree in Literae Humaniores (colloquially Greats).

In 1845, after a short interlude of teaching at Rugby, he was elected Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford. In 1847, he became Private Secretary to Lord Lansdowne, Lord President of the Council. In 1849, he published his first book of poetry, The Strayed Reveller. In 1850 Wordsworth died; Arnold published his "Memorial Verses" on the older poet in Fraser's Magazine.

Arnold often described his duties as a school inspector as "drudgery," although "at other times he acknowledged the benefit of regular work." The inspectorship required him, at least at first, to travel constantly and across much of England. "Initially, Arnold was responsible for inspecting Nonconformist schools across a broad swath of central England. He spent many dreary hours during the 1850s in railway waiting-rooms and small-town hotels, and longer hours still in listening to children reciting their lessons and parents reciting their grievances. But that also meant that he, among the first generation of the railway age, travelled across more of England than any man of letters had ever done. Although his duties were later confined to a smaller area, Arnold knew the society of provincial England better than most of the metropolitan authors and politicians of the day."

Wishing to marry, but unable to support a family on the wages of a private secretary, Arnold sought the position of, and was appointed, in April 1851, one of Her Majesty's Inspector of Schools. Two months later, he married Frances Lucy, daughter of Sir william Wightman, Justice of the Queen's Bench. The Arnolds had six children: Thomas (1852–1868); Trevenen william (1853–1872); Richard Penrose (1855–1908), an inspector of factories; Lucy Charlotte (1858–1934) who married Frederick W. Whitridge of New York, whom she had met during Arnold's American lecture tour; Eleanore Mary Caroline (1861–1936) married (1) Hon. Armine Wodehouse (MP) in 1889, (2) william Mansfield, 1st Viscount Sandhurst, in 1909; Basil Francis (1866–1868).

In 1852, Arnold published his second volume of poems, Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems. In 1853, he published Poems: A New Edition, a selection from the two earlier volumes famously excluding Empedocles on Etna, but adding new poems, Sohrab and Rustum and The Scholar Gipsy. In 1854, Poems: Second Series appeared; also a selection, it included the new poem, Balder Dead.

Arnold's work as a literary critic began with the 1853 "Preface to the Poems". In it, he attempted to explain his extreme act of self-censorship in excluding the dramatic poem "Empedocles on Etna". With its emphasis on the importance of subject in poetry, on "clearness of arrangement, rigor of development, simplicity of style" learned from the Greeks, and in the strong imprint of Goethe and Wordsworth, may be observed nearly all the essential elements in his critical theory. George Watson described the preface, written by the thirty-one-year-old Arnold, as "oddly stiff and graceless when we think of the elegance of his later prose."

Criticism began to take first place in Arnold's writing with his appointment in 1857 to the professorship of poetry at Oxford, which he held for two successive terms of five years. In 1861 his lectures On Translating Homer were published, to be followed in 1862 by Last Words on Translating Homer, both volumes admirable in style and full of striking judgments and suggestive remarks, but built on rather arbitrary assumptions and reaching no well-established conclusions. Especially characteristic, both of his defects and his qualities, are on the one hand, Arnold's unconvincing advocacy of English hexameters and his creation of a kind of literary absolute in the "grand style," and, on the other, his keen feeling of the need for a disinterested and intelligent criticism in England.

Although Arnold's poetry received only mixed reviews and attention during his lifetime, his forays into literary criticism were more successful. Arnold is famous for introducing a methodology of literary criticism somewhere between the historicist approach Common to many critics at the time and the personal essay; he often moved quickly and easily from literary subjects to political and social issues. His Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888), remains a significant influence on critics to this day, and his prefatory essay to that collection, "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time", is one of the most influential essays written on the role of the critic in identifying and elevating literature — even while admitting, "The critical power is of lower rank than the creative." In one of his most famous essays on the topic, "The Study of Poetry", Arnold wrote that, "Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry". He considered the most important criteria used to judge the value of a poem were "high truth" and "high seriousness". By this standard, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales did not merit Arnold's approval. Further, Arnold thought the works that had been proven to possess both "high truth" and "high seriousness", such as those of Shakespeare and Milton, could be used as a basis of comparison to determine the merit of other works of poetry. He also sought for literary criticism to remain disinterested, and said that the appreciation should be of "the object as in itself it really is."

He was led on from literary criticism to a more general critique of the spirit of his age. Between 1867 and 1869 he wrote Culture and Anarchy, famous for the term he popularised for the middle class of the English Victorian era population: "Philistines", a word which derives its modern cultural meaning (in English – the German-language usage was well established) from him. Culture and Anarchy is also famous for its popularisation of the phrase "sweetness and light," first coined by Jonathan Swift.

Arnold is sometimes called the third great Victorian poet, along with Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning. Arnold was keenly aware of his place in poetry. In an 1869 letter to his mother, he wrote:

His religious views were unusual for his time. Scholars of Arnold's works disagree on the nature of Arnold's personal religious beliefs. Under the influence of Baruch Spinoza and his father, Dr. Thomas Arnold, he rejected the supernatural elements in religion, even while retaining a fascination for church rituals. Arnold seems to belong to a middle ground that is more concerned with the poetry of religion and its virtues and values for society than with the existence of God. In the preface to God and the Bible, written in 1875, Arnold recounts a powerful sermon he attended discussing the "salvation by Jesus Christ", he writes: "Never let us deny to this story power and pathos, or treat with hostility ideas which have entered so deep into the life of Christendom. But the story is not true; it never really happened".

In 1887, Arnold was credited with coining the phrase "New Journalism", a term that went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire. However, at the time, the target of Arnold's irritation was not Northcliffe, but the sensational journalism of Pall Mall Gazette Editor, W.T. Stead. Arnold had enjoyed a long and mutually beneficial association with the Pall Mall Gazette since its inception in 1865. As an occasional contributor, he had formed a particular friendship with its first Editor, Frederick Greenwood and a close acquaintance with its second, John Morley. But he strongly disapproved of the muck-raking Stead, and declared that, under Stead, "the P.M.G., whatever may be its merits, is fast ceasing to be literature."

Arnold died suddenly in 1888 of heart failure whilst running to meet a tram that would have taken him to the Liverpool Landing Stage to see his daughter, who was visiting from the United States where she had moved after marrying an American. Mrs. Arnold died in June 1901.

Assessing the importance of Arnold's prose work in 1988, Stefan Collini stated, "for reasons to do with our own cultural preoccupations as much as with the merits of his writing, the best of his prose has a claim on us today that cannot be matched by his poetry." "Certainly there may still be some readers who, vaguely recalling 'Dover Beach' or 'The Scholar Gipsy' from school anthologies, are surprised to find he 'also' wrote prose."

The Writer John Cowper Powys, an admirer, wrote that, "with the possible exception of Merope, Matthew Arnold's poetry is arresting from cover to cover – [he] is the great amateur of English poetry [he] always has the air of an ironic and urbane scholar chatting freely, perhaps a little indiscreetly, with his not very respectful pupils."

His literary career — leaving out the two prize poems — had begun in 1849 with the publication of The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems by A., which attracted little notice and was soon withdrawn. It contained what is perhaps Arnold's most purely poetical poem, "The Forsaken Merman." Empedocles on Etna and Other Poems (among them "Tristram and Iseult"), published in 1852, had a similar fate. In 1858 he published his tragedy of Merope, calculated, he wrote to a friend, "rather to inaugurate my Professorship with dignity than to move deeply the present race of humans," and chiefly remarkable for some experiments in unusual – and unsuccessful – metres.