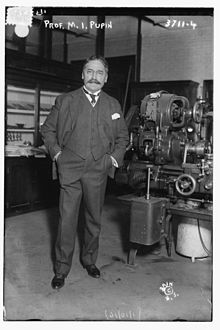

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | October 04, 1858 |

| Birth Place | Idvor, Serbian |

| Age | 161 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 12 March 1935(1935-03-12) (aged 76)\nNew York City, New York, USA |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Citizenship | Serbian, American |

| Alma mater | Columbia College |

| Known for | Long-distance telephone communication |

| Awards | Elliott Cresson Medal (1905) IEEE Medal of Honor (1924) Edison Medal (1920) Pulitzer Prize (1924) John Fritz Medal (1932) |

| Fields | Physics, Invention |

| Doctoral students | Robert Andrews Millikan, Edwin Howard Armstrong |

Net worth

Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin, a renowned physicist from Serbia, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in the year 2024. Pupin's contributions to the field of physics are widely recognized, particularly his work in developing technologies such as X-ray tubes and long-distance telephone communication. Born in Serbia, Pupin's genius and dedication have earned him a stellar reputation worldwide. His estimated net worth indicates the substantial value placed on his scientific achievements and the recognition he has received throughout his career.

Biography/Timeline

Mihajlo Pupin was born on 4 October (22 September, OS) 1858 in the village of Idvor (in the modern-day municipality of Kovačica, Serbia) in Banat, in the Military Frontier in the Austrian Empire. He always remembered the words of his mother and cited her in his autobiography, From Immigrant to Inventor (1925):

Because of his activity in the "Serbian Youth" movement, which at that time had many problems with Austro-Hungarian police authorities, Pupin had to leave Pančevo. In 1872, he went to Prague, where he continued the sixth and first half of the seventh year. After his father died in March 1874, the sixteen-year-old Pupin decided to cancel his education in Prague due to financial problems and to move to the United States.

For the next five years in the United States, Pupin worked as a manual laborer (most notably at the biscuit factory on Cortlandt Street in Manhattan) while he learned English, Greek and Latin. He also gave private lectures. After three years of various courses, in the autumn of 1879 he successfully finished his tests and entered Columbia College, where he became known as an exceptional athlete and scholar. A friend of Pupin's predicted that his physique would make him a splendid oarsman, and that Columbia would do anything for a good oarsman. A popular student, he was elected President of his class in his Junior year. He graduated with honors in 1883 and became an American citizen at the same time.

After Pupin completed his studies, with emphasis in the fields of physics and mathematics, he returned to Europe, initially the United Kingdom (1883–1885), where he continued his schooling at the University of Cambridge. He obtained his Ph.D. at the University of Berlin under Hermann von Helmholtz and in 1889 he returned to Columbia University to become a lecturer of mathematical physics in the newly formed Department of Electrical Engineering. Pupin's research pioneered carrier wave detection and current analysis.

After going to America, he changed his name to Michael Idvorsky Pupin, stressing his origin. His father was named Constantine and mother Olimpijada and Pupin had four brothers and five sisters. In 1888 he married American Sarah Catharine Jackson from New York, with whom he had a daughter named Barbara. They were married only for eight years, because she died from pneumonia.

He was an early investigator into X-ray imaging, but his claim to have made the first X-ray image in the United States is incorrect. He learned of Röntgen's discovery of unknown rays passing through wood, paper, insulators, and thin metals leaving traces on a photographic plate, and attempted this himself. Using a vacuum tube, which he had previously used to study the passage of electricity through rarefied gases, he made successful images on 2 January 1896. Edison provided Pupin with a calcium tungstate fluoroscopic screen which, when placed in front of the film, shortened the exposure time by twenty times, from one hour to a few minutes. Based on the results of experiments, Pupin concluded that the impact of primary X-rays generated secondary X-rays. With his work in the field of X-rays, Pupin gave a lecture at the New York Academy of Sciences. He was the first person to use a fluorescent screen to enhance X-rays for medical purposes. A New York surgeon, Dr. Bull, sent Pupin a patient to obtain an X-ray image of his left hand prior to an operation to remove lead shot from a shotgun injury. The first attempt at imaging failed because the patient, a well-known Lawyer, was "too weak and nervous to be stood still nearly an hour" which is the time it took to get an X-ray photo at the time. In another attempt, the Edison fluorescent screen was placed on a photographic plate and the patient's hand on the screen. X-rays passed through the patients hand and caused the screen to fluoresce, which then exposed the photographic plate. A fairly good image was obtained with an exposure of only a few seconds and showed the shot as if "drawn with pen and ink." Dr. Bull was able to take out all of the lead balls in a very short time.

Pupin's 1899 patent for loading coils, archaically called "Pupin coils", followed closely on the pioneering work of the English Physicist and Mathematician Oliver Heaviside, which predates Pupin's patent by some seven years. The importance of the patent was made clear when the American rights to it were acquired by American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), making him wealthy. Although AT&T bought Pupin's patent, they made little use of it, as they already had their own development in hand led by George Campbell and had up to this point been challenging Pupin with Campbell's own patent. AT&T were afraid they would lose control of an invention which was immensely valuable due to its ability to greatly extend the range of long distance telephones and especially submarine ones.

In 1912, the Kingdom of Serbia named Pupin an honorary consul in the United States. Pupin performed his duties until 1920. During the First World War, Pupin met with Cecil Spring Rice, the British ambassador to the United States, in an attempt to aid Austro-Hungarian Slavs in Canadian custody. Canada had incarcerated some 8,600 so-called Austrians and Hungarians who were deemed to be a threat to national security and were sent to internment camps across the country. The majority, however, turned out to be Ukrainian, but among them were hundreds of Austro-Hungarian Slavs, including Serbs. The British ambassador agreed to allow Pupin to send delegates to visit Canadian internment camps and accept their recommendation of release. Pupin went on to make great contributions to the establishment of international and social relations between the Kingdom of Serbia, and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the United States.

In 1914, Pupin formed "Fund Pijade Aleksić-Pupin" within the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts to commemorate his mother Olimpijada for all the support she gave him through life. Fund assets were used for helping schools in old Serbia and Macedonia, and scholarships were awarded every year on the Saint Sava day. One street in Ohrid was named after Mihajlo Pupin in 1930 to honour his efforts. He also established a separate "Mihajlo Pupin fund" which he funded from his own property in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which he later gave to "Privrednik" for schooling of young people and for prizes in "exceptional achievements in agriculture", as well as for Idvor for giving prizes to pupils and to help the church district.

According to the London agreement from 1915. it was planned that Italy should get Dalmatia. After the secret London agreement France, England and Russia asked from Serbia some territorial concessions to Romania and Bulgaria. Romania should have gotten Banat and Bulgaria should have gotten a part of Macedonia all the way to Skoplje.

When the United States joined the First World War in 1917, Pupin was working at Columbia University, organizing a research group for submarine detection techniques. Together with his colleagues, professors Wils and Morcroft, he performed numerous researches with the aim of discovering submarines at Key West and New London. He also conducted research in the field of establishing telecommunications between places. During the war Pupin was a member of the state council for research and state advisory board for aeronautics. For his work he received a laudative from President Warren G. Harding, which was published on page 386 of his autobiography.

In a difficult situation during the negotiations on the borders of Yugoslavia, Pupin personally wrote a memorandum on 19 March 1919 to American President Woodrow Wilson, who, based on the data received from Pupin about the historical and ethnic characteristics of the border areas of Dalmatia, Slovenia, Istria, Banat, Međimurje, Baranja and Macedonia, stated that he did not recognize the London agreement signed between the allies and Italy.

Besides his patents he published several dozen scientific disputes, articles, reviews and a 396-page autobiography under the name Michael Pupin, From Immigrant to Inventor (Scribner's, 1923). He won the annual Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography. It was published in Serbian in 1929 under the title From pastures to scientist (Od pašnjaka do naučenjaka). Beside this he also published:

Columbia University's Physical Laboratories building, built in 1927, is named Pupin Hall in his honor. It houses the physics and astronomy departments of the university. During Pupin's tenure, Harold C. Urey, in his work with the hydrogen isotope deuterium demonstrated the existence of heavy water, the first major scientific breakthrough in the newly founded laboratories (1931). In 1934 Urey was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the work he performed in Pupin Hall related to his discovery of "heavy hydrogen".

Mihajlo Pupin died in New York City in 1935 at age 76 and was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx.

After World War I, Pupin was already a well-known and acclaimed scientist, as well as a politically influential figure in America. He influenced the final decisions of the Paris peace conference when the borders of the Future kingdom (of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians) were drawn. Pupin stayed in Paris for two months during the peace talk (April–May 1919) on the insistence of the government.

Thanks to Pupin’s donations, the library in Idvor got a reading room, schooling of young people for agriculture sciences was founded, as well as the electrification and waterplant in Idvor. Pupin established a foundation in the museum of Natural History and Arts in Belgrade. The funds of the foundation were used to purchase artistic works of Serbian artists for the museum and for the printing of certain publications. Pupin invested a million dollars in the funds of the foundation.