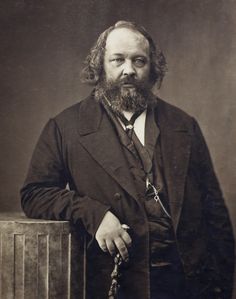

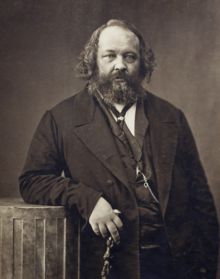

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Philosopher |

| Birth Day | May 30, 1814 |

| Birth Place | Russia, Russian |

| Age | 205 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 1 July 1876(1876-07-01) (aged 62)\nBern, Switzerland |

| Birth Sign | Gemini |

| Era | 19th century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy Western philosophy |

| School | Anarchism Hegelianism (early) |

Net worth

Mikhail Bakunin, a renowned philosopher hailing from Russia, is expected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in the year 2024. Despite his prominence in the field of philosophy, Bakunin's estimated net worth reflects a modest figure. Known for his radical ideas and activism, Bakunin's philosophical contributions have left a lasting impact on the world. However, it appears that his net worth primarily reflects the value of his philosophical works rather than significant material wealth.

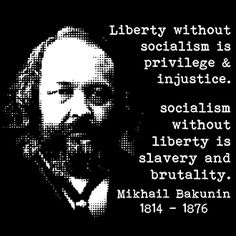

Famous Quotes:

"I must openly admit that in this controversy Marx and Engels were in the right. With characteristic insolence, they attacked Herwegh personally when he was not there to defend himself. In a face-to-face confrontation with them, I heatedly defended Herwegh, and our mutual dislike began then."

Biography/Timeline

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was born to a Russian noble family "of only modest means" (they owned 500 serfs) in the Pryamukhino village situated between Torzhok and Kuvshinovo. His father Alexander Mikhailovich Bakunin (1768—1854) (ru) was a career diplomat who spent years serving in Italy and France and upon his return settled down at the paternal estate and turned a Marshal of Nobility. According to the family legend, the Bakunin dynasty was founded in 1492 by one of the three brothers of the noble Báthory family who left Hungary to serve under Vasili III of Russia. In reality the first documented ancestor was a Moscow dyak (clerk) Nikifor Evdokimov nicknamed Bakunya (from the Russian bakunya, bakulya meaning "chatterbox, phrase monger") who lived during the 17th century. Alexander's mother, knyazna Lubov Petrovna Myshetskaya, belonged to the impoverished Upper Oka Principalities branch of the Rurik dynasty founded by Mikhail Yurievich Tarussky, grandson of Michael of Chernigov.

In 1810 Alexander Bakunin married Varvara Alexandrovna Muravyova (1792—1864) who was 24 years younger than him. She came from the ancient noble Muravyov family that was founded during the 15th century by the Ryazan boyar Ivan Vasilievich Alapovsky nicknamed Muravey (translates simply as "ant") who was granted lands in Veliky Novgorod. Among her second cousins were Nikita Muravyov and Sergey Muravyov-Apostol, some of the key figures of the Decembrist revolt. Alexander's commitment to liberal ideas also led to his involvement with one in the Decembrist clubs. After Nicolas I became an Emperor, however, he gave up politics and devoted himself to the estate and his children — five girls and five boys, the oldest of whom was Mikhail.

At the age of 14 Bakunin left for Saint Petersburg and became a Junker at the Artillery School (known as Mikhailovskaya Military Artillery Academy today). In 1833 he received a rank of Praporshchik and was seconded to serve in the Minsk and Grodno Governorates in one of the artillery brigades. There was a legend that he was sent there as a punishment after offending General Ivan Sukhozanet, a school principal and brother of Nikolai Sukhozanet, but none of the serious sources ever confirmed it, including Bakunin himself. He didn't enjoy army and, having a lot of free time on his hands, spent it on self-education. In 1835 he was seconded to Tver, and from there went straight to his village. Though his father wished him to continue in either the military or the civil Service, Bakunin decided to abandon both and made his way to Moscow, hoping to study philosophy.

In Moscow, Bakunin soon became friends with a group of former university students and engaged in the systematic study of Idealist philosophy, grouped around the poet Nikolay Stankevich, "the bold pioneer who opened to Russian thought the vast and fertile continent of German metaphysics" (E. H. Carr). The philosophy of Kant initially was central to their study, but they progressed to Schelling, Fichte, and Hegel. By autumn 1835, Bakunin had conceived of forming a philosophical circle in his home town of Pryamukhino. Moreover, by early 1836, Bakunin was back in Moscow, where he published translations of Fichte's Some Lectures Concerning the Scholar's Vocation and The Way to a Blessed Life, which became his favorite book. With Stankevich he also read Goethe, Schiller, and E.T.A. Hoffmann.

Nevertheless, Bakunin began warning friends about Nechayev's behavior, and broke off all relations with Nechayev. Others note, moreover, that Bakunin never sought to take personal control of the International, that his secret organisations were not subject to his autocratic power, and that he condemned terrorism as counter-revolutionary. Robert M. Cutler goes further, pointing out that it is impossible fully to understand either Bakunin's participation in the League of Peace and Freedom or the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, or his idea of a secret revolutionary organisation that is immanent in the people, without seeing that they derive from his interpretation of Hegel's dialectic from the 1840s. The script of Bakunin's dialectic, Cutler argues, gave the Alliance the purpose of providing the International with a real revolutionary organisation.

However, Bakunin also wrote of meeting Marx in 1844 that:

Bakunin found Marx's economic analysis very useful and began the job of translating Das Kapital into Russian. In turn Marx wrote of the rebels in the Dresden insurrection of 1848 that "In the Russian refugee Michael Bakunin they found a capable and cool headed leader." Marx wrote to Engels of meeting Bakunin in 1864 after his escape to Siberia saying "On the whole he is one of the few people whom I find not to have retrogressed after 16 years, but to have developed further."

Bakunin played a leading role in the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849, helping to organize the defense of the barricades against Prussian troops with Richard Wagner and Wilhelm Heine. Bakunin was captured in Chemnitz and held for thirteen months before being condemned to death by the government of Saxony. His sentence was commuted to life to allow his extradition to Russia and Austria both of whom were seeking to prosecute him. In June 1850, he was handed over to the Austrian authorities. Eleven months later he received a further death sentence but this too was commuted to life imprisonment. Finally, in May 1851, Bakunin was handed over to the Russian authorities.

Following the death of Nicholas I, the new Tsar, Alexander II personally struck Bakunin's name off the amnesty list. In February 1857 his mother's pleas to the Tsar were finally heeded and he was allowed to go into permanent exile in the western Siberian city of Tomsk. Within a year of arriving in Tomsk, Bakunin married Antonina Kwiatkowska, the daughter of a Polish merchant. He had been teaching her French. In August 1858 Bakunin received a visit from his second cousin, General Count Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, who had been governor of Eastern Siberia for ten years.

Muravyov was a liberal and Bakunin, as his relative, became a particular favourite. In the spring of 1859 Muravyov helped Bakunin with a job for Amur Development Agency which enabled him to move with his wife to Irkutsk, the capital of Eastern Siberia. This enabled Bakunin to be part of the circle involved in political discussions centred on Muravyov's colonial headquarters. Resenting the treatment of the colony by the Saint Petersburg bureaucracy, including its use as a dumping ground for malcontents, a proposal for a United States of Siberia emerged, independent of Russia and federated into a new United States of Siberia and America, following the Example of the United States of America. The circle included Muravyov's young Chief of Staff, Kukel – who Kropotkin related had the complete works of Alexander Herzen – the civil governor Izvolsky, who allowed Bakunin to use his address for correspondence, and Muravyov's deputy and eventual successor, General Alexander Dondukov-Korsakov.

On 5 June 1861 Bakunin left Irkutsk under cover of company Business, ostensibly employed by a Siberian merchant to make a trip to Nikolaevsk. By 17 July he was on board the Russian warship Strelok bound for Kastri. However, in the port of Olga, Bakunin managed to persuade the American captain of the SS Vickery to take him on board. Despite bumping into the Russian Consul on board, Bakunin was able to sail away under the nose of the Russian Imperial Navy. By 6 August he had reached Hakodate in the northernmost Japanese island of Hokkaidō and was soon in Yokohama.

Having re-entered Western Europe, Bakunin immediately immersed himself in the revolutionary movement. In 1860, while still in Irkutsk, Bakunin and his political associates had been greatly impressed by Giuseppe Garibaldi and his expedition to Sicily, during which he declared himself dictator in the name of Victor Emmanuel II. Following his return to London, he wrote to Garibaldi on 31 January 1862:

Bakunin returned to England in September and focussed on Polish affairs. When the Polish insurrection broke out in January 1863, he sailed to Copenhagen where he hoped to join the Polish insurgents. They planned to sail across the Baltic in the SS Ward Jackson to join the insurrection. This attempt failed, and Bakunin met his wife in Stockholm before returning to London. Now he focussed again on going to Italy and his friend Aurelio Saffi wrote him letters of introduction for Florence, Turin and Milan. Mazzini wrote letters of commendation to Federico Campanella in Genoa and Giuseppe Dolfi in Florence. Bakunin left London in November 1863 travelling by way of Brussels, Paris and Vevey (Switzerland) arriving in Italy on 11 January 1864. It was here that he first began to develop his anarchist ideas.

When Bakunin visited Japan after his escape from Siberia, he was not really involved in its politics or with the Japanese peasants. This might be taken as evidence of a basic disinterest in Asia, but that would be incorrect. Bakunin stopped over briefly in Japan as part of a hurried FLIGHT from twelve years of imprisonment, a marked man racing across the world to his European home; he had neither Japanese contacts nor any facility in the Japanese language; the small number of expatriate newspapers by Europeans published in China and Japan provided no insights into local revolutionary conditions or possibilities. Besides, Bakunin's conversion to anarchism came in 1865, towards the end of his life, and four years after his time in Japan.

Giuseppe Fanelli met Bakunin at Ischia in 1866. In October 1868 Bakunin sponsored Fanelli to travel to Barcelona to share his libertarian visions and recruit revolutionists to the International Workingmen's Association. Fanelli's trip and the meeting he organised during his travels provided the catalyst for the Spanish exiles, the largest workers' and peasants' movement in modern Spain and the largest Anarchist movement in modern Europe. Fanelli's tour took him first to Barcelona, where he met and stayed with Elisée Reclus. Reclus and Fanelli were at odds over Reclus' friendships with Spanish republicans, and Fanelli soon left Barcelona for Madrid. Fanelli stayed in Madrid until the end of January 1869, conducting meetings to introduce Spanish workers, including Anselmo Lorenzo, to the First International. In February 1869 Fanelli left Madrid, journeying home via Barcelona. While in Barcelona again, he met with Painter Josep Lluís Pellicer and his cousin, Rafael Farga Pellicer along with others who were to play an important role establishing the International in Barcelona, as well as the Alliance section.

Bakunin played a prominent role in the Geneva Conference (September 1867), and joined the Central Committee. The founding conference was attended by 6,000 people. As Bakunin rose to speak:

In 1868, Bakunin joined the Geneva section of the First International, in which he remained very active until he was expelled from the International by Karl Marx and his followers at the Hague Congress in 1872. Bakunin was instrumental in establishing branches of the International in Italy and Spain.

Between 1869 and 1870, Bakunin became involved with the Russian revolutionary Sergey Nechayev in a number of clandestine projects. However, Bakunin publicly broke with Nechaev over what he described as the latter's "Jesuit" methods, by which all means were justified to achieve revolutionary ends, but privately attempted to maintain contact.

Bakunin was also criticized by Marx and the delegates of the International specifically because his methods of organization were similar to those of Sergey Nechayev, with whom Bakunin was closely associated. While Bakunin rebuked Nechayev upon discovery of his duplicity as well as his amoral politics, he did retain a streak of ruthlessness, as indicated by a 2 June 1870 letter: "Lies, cunning [and] entanglement [are] a necessary and marvelous means for demoralising and destroying the enemy, though certainly not a useful means of obtaining and attracting new friends."

Bakunin was an early proponent of the term "political theology" in his 1871 text "The Political Theology of Mazzini and the International" to which Schmitt's book was a response. Political theology is a branch of both political philosophy and theology that investigates the ways in which theological concepts or ways of thinking underlie political, social, economic and cultural discourses.

Madison contended that it was Bakunin's scheming for control of the First International that brought about his rivalry with Karl Marx and his expulsion from it in 1872: "His approval of violence as a weapon against the agents of oppression led to nihilism in Russia and to individual acts of terrorism elsewhere– with the result that anarchism became generally synonymous with assassination and chaos." However, Bakunin's supporters argue that this "invisible dictatorship" is not a dictatorship in any conventional sense of the word as Bakunin was careful to point out that its members "would not exercise any official political power in the sense of a Leninist vanguard." Their influence would be ideological and freely accepted:

In 1874 he retired with his young wife Antonia Kwiatkowska and three children to Minusio (near Locarno in Switzerland), in a villa called "La Baronata" that the leader of the Italian anarchists Carlo Cafiero had bought for him by selling his own estates in his native town Barletta (Apulia). His daughter Maria Bakunin (1873-1960) became a Chemist and Biologist. His daughter Sofia was the mother of Italian Mathematician Renato Caccioppoli.

Bakunin died in Bern on 1 July 1876; his grave can be found in Bremgarten Cemetery of Bern, box 9201, grave 68. His original epitaph reads: "Remember those who sacrificed everything for the freedom of their country". In 2015 the commemorative plate was replaced in form of a bronze portrait of Bakunin by Swiss Artist Daniel Garbade containing Bakunin's quote: "By striving to do the impossible, man has always achieved what is possible". It was sponsored by the Dadaists of Cabaret Voltaire Zurich, who adopted Bakunin post mortem.

Bakunin is remembered as a major figure in the history of anarchism and as an opponent of Marxism, especially of Marx's idea of dictatorship of the proletariat and for his predictions that Marxist regimes would be one-party dictatorships over the proletariat, not of the proletariat itself. God and the State was translated multiple times by other anarchists, such as Benjamin Tucker, Marie Le Compte and Emma Goldman; and he continues to be an influence on modern-day anarchists, such as Noam Chomsky. Bakunin biographer Mark Leier has asserted that "Bakunin had a significant influence on later thinkers, ranging from Peter Kropotkin and Errico Malatesta to the Wobblies and Spanish anarchists in the Civil War to Herbert Marcuse, E.P. Thompson, Neil Postman, and A.S. Neill, down to the anarchists gathered these days under the banner of 'anti-globalization.'" In short, Bakunin has had a major influence on labour, peasant and leftwing movements, although this was overshadowed from the 1920s by the rise of Marxist regimes. With the collapse of those regimes—and growing awareness of how closely those regimes corresponded to the dictatorships Bakunin predicted—Bakunin's ideas have rapidly gained ground amongst Activists, in some cases again overshadowing Marxism.

Novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his book The Gulag Archipelago (published in 1973) recounts that Bakunin "...abjectly groveled before Nicholas I - thereby avoiding execution. Was this wretchedness of soul? Or revolutionary cunning?"

The standard but hostile English-language biography is by E. H. Carr. A new biography, Bakunin: The Creative Passion, by Mark Leier, was published by St. Martin’s Press August 22, 2006, hardcover, 320 pages, ISBN 0-312-30538-9

In his pre-anarchist years, Bakunin's politics were essentially a left-wing form of nationalism – specifically, a focus on East Europe and Russian affairs. While Bakunin, at this time, located the national liberation and democratic struggles of the Slavs in a larger European revolutionary process, he did not pay much attention to other regions. This aspect of his thought dates from before he became an anarchist, and his anarchist works consistently envisaged a global social revolution, including both Africa and Asia. Bakunin as anarchist continued to stress the importance of national liberation, but he now insisted that this issue had to be solved as part of the social revolution. The same Problem that (in his view) dogged Marxist revolutionary strategy (the capture of revolution by small elite, which would then oppress the masses) would also arise in independence struggles led by nationalism, unless the working class and peasantry created an anarchy:

Bakunin had a different view as compared to Marx's on the revolutionary potential of the lumpenproletariat and the proletariat. As such, "Both agreed that the proletariat would play a key role, but for Marx the proletariat was the exclusive, leading revolutionary agent while Bakunin entertained the possibility that the peasants and even the lumpenproletariat (-proletarians in rags- the unemployed, Common Criminals, etc.) could rise to the occasion." Bakunin "considers workers' integration in capital as destructive of more primary revolutionary forces. For Bakunin, the revolutionary archetype is found in a peasant milieu (which is presented as having longstanding insurrectionary traditions, as well as a communist archetype in its current social form—the peasant commune) and amongst educated unemployed youth, assorted marginals from all classes, brigands, Robbers, the impoverished masses, and those on the margins of society who have escaped, been excluded from, or not yet subsumed in the discipline of emerging industrial work...in short, all those whom Marx sought to include in the category of the lumpenproletariat."

Madelaine Grawitz’s biography (Paris: Calmann Lévy 2000) remains to be translated.