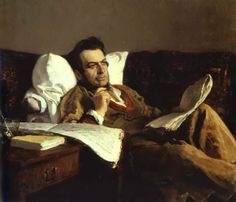

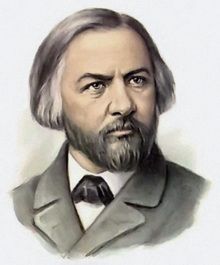

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | June 18, 2001 |

| Birth Place | Smolensk, Russian |

| Age | 19 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | February 15, 1857 |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

Net worth: $1.2 Million (2024)

Mikhail Glinka, the renowned Russian composer, has an estimated net worth of $1.2 million as of 2024. With his exceptional talent for composing music, Glinka has not only cemented his place in the annals of classical music but has also enjoyed significant financial success. Throughout his illustrious career, Glinka has composed some of the most influential and celebrated works in Russian music history. His compositions, characterized by their distinctive nationalistic style, have captivated audiences worldwide, leading to widespread acclaim and financial prosperity. Glinka's immense net worth is a testament to his enduring legacy as a composer and his invaluable contributions to the world of music.

Biography/Timeline

In 1830, at the recommendation of a physician, Glinka decided to travel to Italy with the tenor Nikolai Kuzmich Ivanov. The journey took a leisurely pace, ambling uneventfully through Germany and Switzerland, before they settled in Milan. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory with Francesco Basili, although he struggled with counterpoint, which he found irksome. Although he spent his three years in Italy listening to Singers of the day, romancing women with his music, and meeting many famous people including Mendelssohn and Berlioz, he became disenchanted with Italy. He realized that his mission in life was to return to Russia, write in a Russian manner, and do for Russian music what Donizetti and Bellini had done for Italian music. His return route took him through the Alps, and he stopped for a while in Vienna, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt. He stayed for another five months in Berlin, during which time he studied composition under the distinguished Teacher Siegfried Dehn. A Capriccio on Russian themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on two Russian themes were important products of this period.

A lesser work that received attention in the last decade of the 20th century was Glinka's "The Patriotic Song", supposedly written for a contest for a national anthem in 1833. In 1990, Supreme Soviet of Russia adopted it as the anthem of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, which had been the only one of the Soviet republics without its own anthem. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the hymn was confirmed as the Russian national anthem in 1993; it remained until 2000.

When word reached Glinka of his father's death in 1834, he left Berlin and returned to Novospasskoye.

A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka's two great operas. It was originally entitled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, it tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin who sacrifices his life for the Tsar by leading astray a group of marauding Poles who were hunting him. The Tsar himself followed the work's progress with interest and suggested the change in the title. It was a great success at its premiere on 9 December 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. Although the music is still more Italianate than Russian, Glinka shows superb handling of the recitative which binds the whole work, and the orchestration is masterly, foreshadowing the orchestral writing of later Russian composers. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4,000 rubles. (During the Soviet era, the opera was staged under its original title Ivan Susanin).

In 1837, Glinka was installed as the instructor of the Imperial Chapel Choir, with a yearly salary of 25,000 rubles, and lodging at the court. In 1838, at the suggestion of the Tsar, he went off to Ukraine to gather new voices for the choir; the 19 new boys he found earned him another 1,500 rubles from the Tsar.

He soon embarked on his second opera: Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Alexander Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently, the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka's music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. He uses a descending whole tone scale in the famous overture. This is associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev. There is much Italianate coloratura, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but his great achievement in this opera lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it was first performed on 9 December 1842, it met with a cool reception, although it subsequently gained popularity.

Outside Russia several of Glinka's orchestral works have been fairly popular in concerts and recordings. Besides the well-known overtures to the operas (especially the brilliantly energetic overture to Ruslan), his major orchestral works include the symphonic poem Kamarinskaya (1848), based on Russian folk tunes, and two Spanish works, A Night in Madrid (1848, 1851) and Jota Aragonesa (1845). Glinka also composed many art songs, many piano pieces, and some chamber music.

Glinka went through a dejected year after the poor reception of Ruslan and Lyudmila. His spirits rose when he travelled to Paris and Spain. In Spain, Glinka met Don Pedro Fernández, who remained his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life. In Paris, Hector Berlioz conducted some excerpts from Glinka’s operas and wrote an appreciative article about him. Glinka in turn admired Berlioz’s music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. Another visit to Paris followed in 1852 where he spent two years, living quietly and making frequent visits to the botanical and zoological gardens. From there he moved to Berlin where, after five months, he died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. He was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and re-interred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

In 1884, Mitrofan Belyayev founded the "Glinka Prize", which was awarded annually. In the first years the winners included Alexander Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Cesar Cui and Anatoly Lyadov.

The modern Russian music critic Viktor Korshikov thus summed up: "There is not the development of Russian musical culture without...three operas – Ivan Soussanine, Ruslan and Ludmila and the Stone Guest have created Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin. Soussanine is an opera where the main character is the people, Ruslan is the mythical, deeply Russian intrigue, and in Guest, the drama dominates over the softness of the beauty of sound." Two of these operas – Ivan Soussanine and Ruslan and Ludmila – were composed by Glinka.