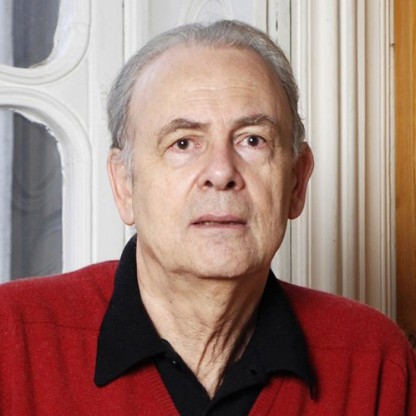

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Writer and Philisopher |

| Birth Day | July 12, 1812 |

| Birth Place | Shaki, Azerbaijan, Azerbaijani |

| Age | 207 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 9 March 1878(1878-03-09) (aged 65)\nTiflis, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Occupation | Playwright, philosopher |

Net worth: $17 Million (2024)

Mirza Fatali Akhundov, revered as a prominent writer and philosopher in Azerbaijani history, is projected to have a net worth of $17 million in 2024. Akhundov's literary contributions enriched the cultural landscape of Azerbaijan, laying the foundation for its modern literature. His works encompassed a vast range of genres, including essays, plays, and novels, which resonated with readers across the nation. Through his insightful philosophies, Akhundov stimulated intellectual dialogues and inspired critical thinking among his contemporaries. Today, his legacy endures as a testament to his profound influence on Azerbaijani literature and intellectual discourse.

Famous Quotes:

The greatest Azerbaidzhani poet of the nineteenth century, Mirza Fathali Akhundov (1812-78), who is called the "Molière of the Orient", was so completely devoted to the Russian cause that he urged his compatriots to fight Turkey during the Crimean War.

Biography/Timeline

Akhundzade was born in 1812 in Nukha (present-day Shaki, Azerbaijan) to a wealthy land owning family from Iranian Azerbaijan. His parents, and especially his uncle Haji Alaskar, who was Fatali's first Teacher, prepared young Fatali for a career in Shi'a clergy, but the young man was attracted to the literature. In 1832, while in Ganja, Akhundzade came into contact with the poet Mirza Shafi Vazeh, who introduced him to a Western secular thought and discouraged him from pursuing a religious career. Later in 1834 Akhundzade moved to Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, Georgia), and spent the rest of his life working as a translator of Oriental languages in the Service of the Russian Empire's Viceroyalty. Concurrently, from 1837 onwards he worked as a Teacher in Tbilisi uezd Armenian school, then in Nersisyan school. In Tiflis his acquaintance and friendship with the exiled Russian Decembrists Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, Vladimir Odoyevsky, poet Yakov Polonsky, Armenian Writers Khachatur Abovian, Gabriel Sundukyan and others played some part in formation of Akhundzade's Europeanized outlook.

Akhundzade identified himself as belonging to the nation of Iran (mellat-e Irān) and to the Iranian homeland (waṭan). He corresponded with Jālāl-al-Din Mirzā (a minor Qajar Prince, son of Bahman Mirza Qajar,1826–70) and admired this latter's epic Nāmeh-ye Khosrovān ('Book of Sovereigns'), which was an attempt to offer the modern reader a biography of Iran's ancient kings, real and mythical, without recourse to any Arabic loanword. The Nāmeh presented the pre-Islamic past as one of grandeur, and the advent of Islam as a radical rupture.

Akhundzade's first published work was The Oriental Poem (1837), written to lament the death of the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. But the rise of Akhundzade's literary activity comes in the 1850s. In the first half of the 1850s, Akhundzade wrote six comedies – the first comedies in Azerbaijani literature as well as the first samples of the national dramaturgy. The comedies by Akhundzade are unique in their critical pathos, analysis of the realities in Azerbaijan of the first half of the 19th century. These comedies found numerous responses in the Russian other foreign periodical press. The German Magazine of Foreign Literature called Akhundzade "dramatic genius", "the Azerbaijani Molière" 1. Akhundzade's sharp pen was directed against everything that he believed hindered the advance of the Russian Empire, which for Akhundzadeh was a force for modernisation, in spite of the atrocities it committed in its southern advance against Akhundzadeh's own kin. According to Walter Kolarz:

Well ahead of his time, Akhundzade was a keen advocate for alphabet reform, recognizing deficiencies of Perso-Arabic script with regards to Turkic sounds. He began his work regarding alphabet reform in 1850. His first efforts focused on modifying the Perso-Arabic script so that it would more adequately satisfy the phonetic requirements of the Azerbaijani language. First, he insisted that each sound be represented by a separate symbol - no duplications or omissions. The Perso-Arabic script expresses only three vowel sounds, whereas Azeri needs to identify nine vowels. Later, he openly advocated the change from Perso-Arabic to a modified Latin alphabet. The Latin script which was used in Azerbaijan between 1922 and 1939, and the Latin script which is used now, were based on Akhundzade's third version.

Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani (1854-96) was one of Akhundzades disciples, and three decades later will endeavour to disseminate Akhundzade's thought while also significantly strengthening its racial content (Zia-Ebrahimi argues that Kermani was the first to retrieve the idea of 'the Aryan race' from European texts and refer to it as such, the modern idea of race here being different to the various cognates of the term 'Ariya' that one finds in ancient sources). Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani also followed Jalāl-al-Din Mirzā in producing a national history of Iran, Āʾine-ye sekandari (The Alexandrian Mirror), extending from the mythological past to the Qajar era, again to contrast a mythified and fantasised pre-Islamic past with a present that falls short of nationalist expectations..

In 1859 Akhundzade published his short but famous novel The Deceived Stars. In this novel he laid the foundation of Azerbaijani realistic historical prose, giving the Models of a new genre in Azerbaijani literature. By his comedies and dramas Akhundzade established realism as the leading trend in Azerbaijani literature.

In the 1920s, the Azerbaijan State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre was named after Akhundzade.

Zia-Ebrahimi sees dislocative nationalism as the dominant paradigm of identity in modern Iran, as it became part and parcel of the official ideology of the Pahlavi State (1925-79) and thus disseminated through mass-schooling, propaganda, and the state's symbolic repertoire.

Punik, town in Armenia was also named in the honour of Akhundzade until very recently. TURKSOY hosted a groundbreaking ceremony to declare 2012 as year of Mirza Fatali Akhundzade.