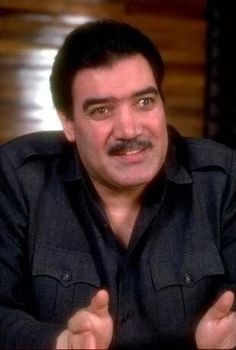

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | President of Afghanistan |

| Birth Year | 1947 |

| Birth Place | Gardez, Afghan |

| Age | 73 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 28 September 1996(1996-09-28) (aged 49)\nKabul, Afghanistan |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Prime Minister | Babrak Karmal Sultan Ali Keshtmand |

| Preceded by | Assadullah Sarwari |

| Succeeded by | Ghulam Faruq Yaqubi |

| President | Babrak Karmal |

| Political party | People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (Parcham) |

| Spouse(s) | Dr. Fatana Najib |

| Children | three daughters |

| Alma mater | Kabul University |

Net worth: $700,000 (2024)

Mohammad Najibullah, famously known as the President of Afghanistan, is expected to have a net worth of approximately $700,000 by 2024. Serving as the president of a country posed its own set of challenges and responsibilities, making his estimated net worth quite respectable. Najibullah's involvement in the Afghan political landscape further underlines his significance, as he navigated through a turbulent period in the country's history. Despite the difficulties, his dedication to public service and leadership has evidently contributed to his financial success.

Biography/Timeline

Najibullah was born in February 1947 in the city of Kabul, in the Kingdom of Afghanistan. His ancestral village is located between the towns of Said Karam and Gardēz in Paktia Province, this place is known as Mehlan. He was educated at Habibia High School in Kabul, St. Joseph's School in Baramulla, India and Kabul University, where he graduated with a Doctor degree in Medicine in 1975. He belongs to the Ahmadzai sub-tribe of the Ghilzai Pashtun tribe in Gardiz.

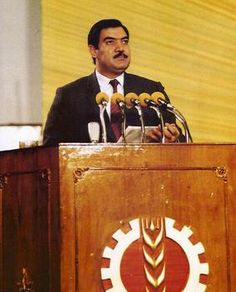

In 1965 Najibullah joined the Parcham faction of the Communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). He served as Babrak Karmal's close associate and bodyguard during the latter's tenure in the lower house of parliament (1965–1973), Najibullah earned the nickname Najib-e-Gaw (Najib the Bull) due in equal parts to his imposing heft and temperament. In 1977 he was elected to the Central Committee.

In April 1978 the PDPA took power in Afghanistan, with Najibullah a member of the ruling Revolutionary Council. However, the Khalq faction of the PDPA gained supremacy over his own Parcham faction, and after a brief stint as Ambassador to Iran, he was dismissed from government and went into exile in Europe.

He returned to Kabul after the Soviet intervention in 1979. In 1980, he was appointed the head of KHAD, the Afghan equivalent to the Soviet KGB, and was promoted to the rank of Major General. He was appointed following lobbying made by the Soviets, most notable among them was Yuri Andropov, the KGB Chairman. During his six years as head of KHAD he had two to four deputies under his command, who in turn were responsible for an estimated 12 departments. According to evidence, Najibullah was dependent on his family and his professional network, and appointed more often than not people he knew to top positions within the KHAD. In June 1981, Najibullah, along with Mohammad Aslam Watanjar, a former tank commander and the then Minister of Communications and Major General Mohammad Rafi, the Minister of Defence were appointed to the PDPA Politburo. Under Najibullah, KHAD's personnel increased from 120 to 25,000 to 30,000. KHAD employees were amongst the best-paid government bureaucrats in communist Afghanistan, and because of it, the political indoctrination of KHAD officials was a top priority. During a PDPA conference Najibullah, talking about the indoctrination programme of KHAD officials, said "a weapon in one hand, a book in the other." Terrorist activities launched by KHAD reached its peak under Najibullah. He reported directly to the Soviet KGB, and a big part of KHAD's budget came from the Soviet Union itself.

During Najibullah's tenure as KHAD head, it became one of the most brutally efficient governmental organs. Because of this, he gained the attention of several leading Soviet officials, such as Yuri Andropov, Dmitriy Ustinov and Boris Ponomarev. In 1981, Najibullah was appointed to the PDPA Politburo. In 1985 Najibullah stepped down as state security minister to focus on PDPA politics; he had been appointed to the PDPA Secretariat. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, was able to get Karmal to step down as PDPA General Secretary in 1986, and replace him with Najibullah. For a number of months Najibullah was locked in a power struggle against Karmal, who still retained his post of Chairman of the Revolutionary Council. Najibullah accused Karmal of trying to wreck his policy of National Reconciliation, which were a series of efforts by Najibullah to end the conflict.

While he may have been the de jure leader of Afghanistan, Soviet advisers still did the majority of work when Najibullah took power. As Gorbachev remarked "We're still doing everything ourselves [...]. That's all our people know how to do. They've tied Najibullah hand and foot." Fikryat Tabeev, the Soviet ambassador to Afghanistan, was accused of acting like a governor general by Gorbachev. Tabeev was recalled from Afghanistan in July 1986, but while Gorbachev called for the end of Soviet management of Afghanistan, he could not help but to do some managing himself. At a Soviet Politburo meeting, Gorbachev said "It's difficult to build a new building out of old material [...] I hope to God that we haven't made a mistake with Najibullah." As time would prove, the Problem was that Najibullah's aim were the opposite of the Soviet Union's; Najibullah was opposed to a Soviet withdrawal, the Soviet Union wanted a Soviet withdrawal. This was logical, considering the fact that the Afghan military was on the brink of dissolution. The only means of survival seemed to Najibullah was to retain the Soviet presence. In July 1986 six regiments, which consisted up to 15,000 troops, were withdrawn from Afghanistan. The aim of this early withdrawal was, according to Gorbachev, to show the world that the Soviet leadership was serious about leaving Afghanistan. The Soviets told the United States Government that they were planning to withdraw, but the United States Government didn't believe it. When Gorbachev met with Ronald Reagan during his visit the United States, Reagan called, bizarrely, for the dissolution of the Afghan army.

During Babrak Karmal's later years, and during Najibullah's tenure, the PDPA tried to improve their standing with Muslims by moving, or appearing to move, to the political centre. They wanted to create a new image for the party and state. In 1987 Najibullah re-added Ullah to his name to appease the Muslim community. Communist symbols were either replaced or removed. These measures did not contribute to any notable increase in support for the government, because the mujahideen had a stronger legitimacy to protect Islam than the government; they had rebelled against what they saw as an anti-Islamic government, that government was the PDPA. Islamic principles were embedded in the 1987 constitution, for instance, Article 2 of the constitution stated that Islam was the state religion, and Article 73 stated that the head of state had to be born into a Muslim Afghan family. The 1990 constitution stated that Afghanistan was an Islamic state, and the last references to communism were removed. Article 1 of the 1990 Constitution said that Afghanistan was an "independent, unitary and Islamic state."

On 14 April 1988 the Afghan and Pakistani governments signed the Geneva Accords, and the Soviet Union and the United States signed as guarantors; the treaty specifically stated that the Soviet military had to withdraw from Afghanistan by 15 February 1989. Gorbachev later confided to Anatoly Chernyaev, a personal advisor to Gorbachev, that the Soviet withdrawal would be criticised for creating a bloodbath which could have been averted if the Soviets stayed. During a Politburo meeting Eduard Shevardnadze said "We will leave the country in a deplorable situation", and further talked about the economic collapse, and the need to keep at least 10 to 15,000 troops in Afghanistan. In this Vladimir Kryuchkov, the KGB Chairman, supported him. This stance, if implemented, would be a betrayal of the Geneva Accords just signed. During the second phase of the Soviet withdrawal, in 1989, Najibullah told Valentin Varennikov openly that he would do everything to slow down the Soviet departure. Varennikov in turn replied that such a move would not help, and would only lead to an international outcry against the war. Najibullah would repeat his position later that year, to a group of senior Soviet representatives in Kabul. This time Najibullah stated that Ahmad Shah Massoud was the main Problem, and that he needed to be killed. In this, the Soviets agreed, but repeated that such a move would be a breach of the Geneva Accords; to hunt for Massoud so early on would disrupt the withdrawal, and would mean that the Soviet Union would fail to meet its deadline for withdrawal.

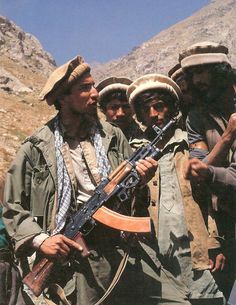

With the Soviets' withdrawal in 1989, the Afghan army was left on its own to battle the insurgents. The most effective, and largest, assaults on the mujahideen were undertaken during the 1985–86 period. These offensives had forced the mujahideen on the defensive near Herat and Kandahar. The Soviets ensued a bomb and negotiate during 1986, and a major offensive that year included 10,000 Soviet troops and 8,000 Afghan troops.

Hardline Khalqist Shahnawaz Tanai attempted to overthrow Najibullah in a failed coup attempt in March 1990.

From 1989 to 1990, the Najibullah government was partially successful in building up the Afghan defence forces. The Ministry of State Security had established a local milita force which stood at an estimated 100,000 men. The 17th Division in Herat, which had begun the 1979 Herat uprising against PDPA-rule, stood at 3,400 regular troops and 14,000 tribal men. In 1988, the total number of security forces available to the government stood at 300,000. This trend did not continue, and by the summer of 1990, the Afghan government forces were on the defensive again. By the beginning of 1991, the government controlled only 10 percent of Afghanistan, the eleven-year Siege of Khost had ended in a mujahideen victory and the morale of the Afghan military finally collapsed. In the Soviet Union, Kryuchkov and Shevardnadze had both supported continuing aid to the Najibullah government, but Kryuchkov had been arrested following the failed 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt and Shevardnadze had resigned from his posts in the Soviet government in December 1990 – there were no longer any pro-Najibullah people in the Soviet leadership and the Soviet Union was in the middle of an economic and political crisis, which would lead directly to the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991. At the same time Boris Yeltsin became Russia's new hope, and he had no wish to continue to aid Najibullah's government, which he considered a relic of the past. In the autumn of 1991, Najibullah wrote to Shevardnadze "I didn't want to be President, you talked me into it, insisted on it, and promised support. Now you are throwing me and the Republic of Afghanistan to its fate."

On March 18, 1992, Najibullah offered his government's immediate resignation, and followed the United Nations (UN) plan to be replaced by an interim government with all parties involved in the struggle. In mid-April Najibullah accepted a UN plan to hand power to a seven-man council, and several days later on 14 April, Najibullah was forced to resign on the orders of the Watan Party because of the loss of Bagram Airbase and the town of Charikar. Abdul Rahim Hatef became acting head of state following Najibullah's resignation. The mujahideen forces took Kabul shortly thereafter and most of them signed the Peshawar Accord, creating the new Islamic State of Afghanistan.

In 1994, India sent senior diplomat M K Bhadrakumar to Kabul to hold talks with Ahmad Shah Massoud, the defence minister, to consolidate relations with the Afghan authorities, reopen the embassy, and allow Najibullah to fly to India, but Massoud refused. Bhadrakumar wrote in 2016 that he believed Massoud did not want Najibullah to leave as Massoud could strategically make use of him, and that Massoud "probably harboured hopes of a co-habitation with Najib somewhere in the womb of time because that extraordinary Afghan Politician was a strategic asset to have by his side". At the time, Massoud was commanding the government's forces fighting the militias of Dostum and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar during the Battle of Kabul.

In September 1996 when the Pakistan-backed Taliban were about to enter Kabul, Massoud offered Najibullah an opportunity to flee Kabul. Najibullah refused. The reasons as to why he refused remain unclear. Massoud himself has claimed that Najibullah feared that "if he fled with the Tajiks, he would be for ever damned in the eyes of his fellow Pashtuns." Others, like general Tokhi, who was with Dr. Najibullah until the day before his torture and execution, have stated that Najibullah mistrusted Massoud after his militia had repeatedly put the UN compound under rocket fire and had effectively barred Najibullah from leaving Kabul. "If they wanted Najibullah to flee Kabul in safety," Tokhi said, "they could have provided him the opportunity as they did with other high ranking officials from the communist party from 1992 to 1996." Thus when Massoud's militia came to both Dr. Najibullah and General Tokhi and asked them to come with them to flee Kabul, they rejected the offer. Najibullah was at the UN compound when the Taliban Soldiers came for him on the evening of 26 September 1996. The Taliban shot him in the head and then dragged his dead, mutilated and castrated body behind a truck through the streets. His brother Ahmadzai was given the same treatment. Najibullah and Ahmadzai's bodies were hanged on public display in order to show the public that a new era had begun. At first Najibullah and Ahmadzai were denied an Islamic funeral because of their "crimes", but the bodies were later handed over to the International Committee of the Red Cross who in turn sent their bodies to Paktia Province where both of them were given a proper funeral by their fellow Ahmadzai tribesmen.

After his death, the brutal civil war between mujahideen factions, followed by the hardline Taliban regime, dramatically changed Najibullah's image to a more positive stance. Najibullah was seen as a strong and patriotic leader. Since the 2010s, posters and pictures of him are a Common sight in many Afghan cities.

On July 28, 2017, thousands attended an event at a Kabul hotel for the fourth “consultative gathering for a legal relaunch of Hezb-e Watan [Homeland Party]”.