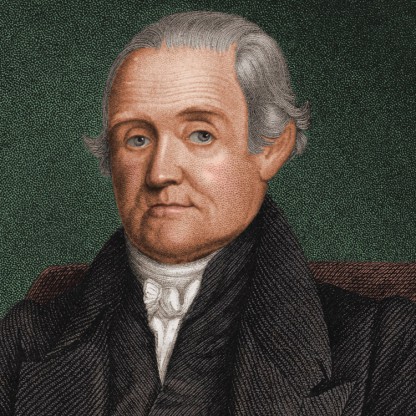

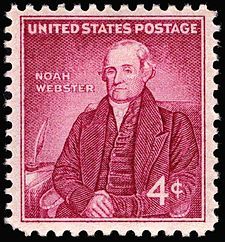

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Lexicographer |

| Birth Day | October 16, 1758 |

| Birth Place | West Hartford, United States |

| Age | 261 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | May 28, 1843(1843-05-28) (aged 84)\nNew Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Scorpio |

| Resting place | Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse(s) | Rebecca Greenleaf Webster (m. 1789) |

| Children | 8 |

| Residence | Hartford, Connecticut New York City New Haven, Connecticut |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Occupation | Lexicographer Author Connecticut state representative |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | Connecticut Militia |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

Net worth

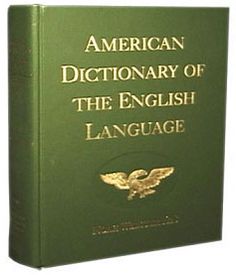

Noah Webster, best known as a lexicographer in the United States, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in 2024. Webster's immense contribution to American English cannot be overstated, as his comprehensive dictionary, first published in 1828, revolutionized language usage and standardization in the country. With his meticulous work, he not only provided a comprehensive guide to words but also contributed significantly to the development of a distinctly American identity. Today, his legacy lives on, and his net worth estimates highlight the enduring impact and importance of his linguistic contributions.

Famous Quotes:

America sees the absurdities—she sees the kingdoms of Europe, disturbed by wrangling sectaries, or their commerce, population and improvements of every kind cramped and retarded, because the human mind like the body is fettered 'and bound fast by the chords of policy and superstition': She laughs at their folly and shuns their errors: She founds her empire upon the idea of universal toleration: She admits all religions into her bosom; She secures the sacred rights of every individual; and (astonishing absurdity to Europeans!) she sees a thousand discordant opinions live in the strictest harmony ... it will finally raise her to a pitch of greatness and lustre, before which the glory of ancient Greece and Rome shall dwindle to a point, and the splendor of modern Empires fade into obscurity.

Biography/Timeline

Webster was born in the Western Division of Hartford (which became West Hartford, Connecticut) to an established family. His father Noah Sr. (1722–1813) was a descendant of Connecticut Governor John Webster; his mother Mercy (Steele) Webster (1727–1794) was a descendant of Governor william Bradford of Plymouth Colony. His father was primarily a farmer, though he was also deacon of the local Congregational church, captain of the town's militia, and a founder of a local book society (a precursor to the public library). After American independence, he was appointed a justice of the peace.

In terms of political theory, he de-emphasized virtue (a core value of republicanism) and emphasized widespread ownership of property (a key element of Federalism). He was one of the few Americans who paid much attention to French theorist Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was not Rousseau's politics but his ideas on pedagogy in Emile (1762) that influenced Webster in adjusting his Speller to the stages of a child's development.

Webster lacked career plans after graduating from Yale in 1778, later writing that a liberal arts education "disqualifies a man for business". He taught school briefly in Glastonbury, but the working conditions were harsh and the pay low. He quit to study law. While studying law under Future U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, Webster also taught full-time in Hartford—which was grueling, and ultimately impossible to continue. He quit his legal studies for a year and lapsed into a depression; he then found another practicing attorney to tutor him, and completed his studies and passed the bar examination in 1781. As the Revolutionary War was still going on, he could not find work as a Lawyer. He received a master's degree from Yale by giving an oral dissertation to the Yale graduating class. Later that year, he opened a small private school in western Connecticut that was a success. Nevertheless, he soon closed it and left town, probably because of a failed romance. Turning to literary work as a way to overcome his losses and channel his ambitions, he began writing a series of well-received articles for a prominent New England newspaper justifying and praising the American Revolution and arguing that the separation from Britain was permanent. He then founded a private school catering to wealthy parents in Goshen, New York and, by 1785, he had written his speller, a grammar book and a reader for elementary schools. Proceeds from continuing sales of the popular blue-backed speller enabled Webster to spend many years working on his famous dictionary.

Webster was by nature a revolutionary, seeking American independence from the cultural thralldom to Britain. To replace it, he sought to create a utopian America, cleansed of luxury and ostentation and the champion of freedom. By 1781, Webster had an expansive view of the new nation. American nationalism was superior to Europe because American values were superior, he claimed.

As a Teacher, he had come to dislike American elementary schools. They could be overcrowded, with up to seventy children of all ages crammed into one-room schoolhouses. They had poor, underpaid staff, no desks, and unsatisfactory textbooks that came from England. Webster thought that Americans should learn from American books, so he began writing the three volume compendium A Grammatical Institute of the English Language. The work consisted of a speller (published in 1783), a grammar (published in 1784), and a reader (published in 1785). His goal was to provide a uniquely American approach to training children. His most important improvement, he claimed, was to rescue "our native tongue" from "the clamour of pedantry" that surrounded English grammar and pronunciation. He complained that the English language had been corrupted by the British aristocracy, which set its own standard for proper spelling and pronunciation. Webster rejected the notion that the study of Greek and Latin must precede the study of English grammar. The appropriate standard for the American language, argued Webster, was "the same republican principles as American civil and ecclesiastical constitutions." This meant that the people-at-large must control the language; popular sovereignty in government must be accompanied by popular usage in language.

Part three of his Grammatical Institute (1785) was a reader designed to uplift the mind and "diffuse the principles of virtue and patriotism."

The speller was originally titled The First Part of the Grammatical Institute of the English Language. Over the course of 385 editions in his lifetime, the title was changed in 1786 to The American Spelling Book, and again in 1829 to The Elementary Spelling Book. Most people called it the "Blue-Backed Speller" because of its blue cover and, for the next one hundred years, Webster's book taught children how to read, spell, and pronounce words. It was the most popular American book of its time; by 1837, it had sold 15 million copies, and some 60 million by 1890—reaching the majority of young students in the nation's first century. Its royalty of a half-cent per copy was enough to sustain Webster in his other endeavors. It also helped create the popular contests known as spelling bees.

Webster dedicated his Speller and Dictionary to providing an intellectual foundation for American nationalism. From 1787 to 1789, Webster was an outspoken supporter of the new Constitution. In October 1787, he wrote a pamphlet entitled "An Examination into the Leading Principles of the Federal Constitution Proposed by the Late Convention Held at Philadelphia," published under the pen name "A Citizen of America." The pamphlet was influential, particularly outside New York State.

Noah Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf (1766–1847) on October 26, 1789, New Haven, Connecticut. They had eight children:

Webster helped found the Connecticut Society for the Abolition of Slavery in 1791, but by the 1830s rejected the new tone among abolitionists that emphasized Americans who tolerated slavery were themselves sinners. In 1837, Webster warned his daughter Eliza about her fervent support of the abolitionist cause. Webster wrote, "slavery is a great sin and a general calamity—but it is not our sin, though it may prove to be a terrible calamity to us in the north. But we cannot legally interfere with the South on this subject." He added, "To come north to preach and thus disturb our peace, when we can legally do nothing to effect this object, is, in my view, highly Criminal and the Preachers of abolitionism deserve the penitentiary."

Webster followed French radical thought and urged a neutral foreign policy when France and Britain went to war in 1793. French minister Citizen Genêt set up a network of pro-Jacobin "Democratic-Republican Societies" that entered American politics and attacked President Washington, and Webster condemned them. He called on fellow Federalist editors to "all agree to let the clubs alone—publish nothing for or against them. They are a plant of exotic and forced birth: the sunshine of peace will destroy them." He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1799.

For decades, he was one of the most prolific authors in the new nation, publishing textbooks, political essays, a report on infectious diseases, and newspaper articles for his Federalist party. He wrote so much that a modern bibliography of his published works required 655 pages. He moved back to New Haven in 1798; he was elected as a Federalist to the Connecticut House of Representatives in 1800 and 1802–1807.

Nathan Austin has explored the intersection of lexicographical and poetic practices in American literature, and attempts to map out a "lexical poetics" using Webster's definitions as his base. Poets mined his dictionaries, often drawing upon the lexicography in order to express word play. Austin explicates key definitions from both the Compendious (1806) and American (1828) dictionaries, and finds a range of themes such as the politics of "American" versus "British" English and issues of national identity and independent culture. Austin argues that Webster's dictionaries helped redefine Americanism in an era of highly flexible cultural identity. Webster himself saw the dictionaries as a nationalizing device to separate America from Britain, calling his project a "federal language", with competing forces towards regularity on the one hand and innovation on the other. Austin suggests that the contradictions of Webster's lexicography were part of a larger play between liberty and order within American intellectual discourse, with some pulled toward Europe and the past, and others pulled toward America and the new Future.

Webster in early life was something of a freethinker, but in 1808 he became a convert to Calvinistic orthodoxy, and thereafter became a devout Congregationalist who preached the need to Christianize the nation. Webster grew increasingly authoritarian and elitist, fighting against the prevailing grain of Jacksonian Democracy. Webster viewed language as a tool to control unruly thoughts. His American Dictionary emphasized the virtues of social control over human passions and individualism, submission to authority, and fear of God; they were necessary for the maintenance of the American social order. As he grew older, Webster's attitudes changed from those of an optimistic revolutionary in the 1780s to those of a pessimistic critic of man and society by the 1820s.

He moved to Amherst, Massachusetts in 1812, where he helped to found Amherst College. In 1822 the family moved back to New Haven, where Webster was awarded an honorary degree from Yale the following year. He is buried in New Haven's Grove Street Cemetery.

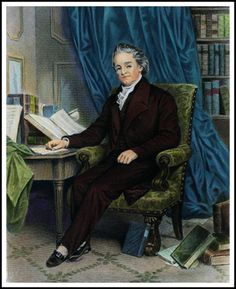

Webster completed his dictionary during his year abroad in January 1825 in a boarding house in Cambridge, England. His book contained seventy thousand words, of which twelve thousand had never appeared in a published dictionary before. As a spelling reformer, Webster preferred spellings that matched pronunciation better. In A Companion to the American Revolution (2008), John Algeo notes: "It is often assumed that characteristically American spellings were invented by Noah Webster. He was very influential in popularizing certain spellings in America, but he did not originate them. Rather […] he chose already existing options such as center, color and check on such grounds as simplicity, analogy or etymology." He also added American words, like "skunk" and "squash", that did not appear in British dictionaries. At the age of seventy, Webster published his dictionary in 1828, registering the copyright on April 14.

His 1828 American Dictionary contained the greatest number of Biblical definitions given in any reference volume. Webster considered education "useless without the Bible." Webster released his own edition of the Bible in 1833, called the Common Version. He used the King James Version (KJV) as a base and consulted the Hebrew and Greek along with various other versions and commentaries. Webster molded the KJV to correct grammar, replaced words that were no longer used, and did away with words and phrases that could be seen as offensive.

The Copyright Act of 1831 was the first major statutory revision of U.S. copyright law, a result of intensive lobbying by Noah Webster and his agents in Congress. Webster also played a critical role lobbying individual states throughout the country during the 1780s to pass the first American copyright laws, which were expected to have distinct nationalistic implications for the infant nation.

In 1840, the second edition was published in two volumes. On May 28, 1843, a few days after he had completed revising an appendix to the second edition, and with much of his efforts with the dictionary still unrecognized, Noah Webster died. The rights to his dictionary were acquired by George and Charles Merriam in 1843 from Webster's estate and all contemporary Merriam-Webster dictionaries trace their lineage to that of Webster, although many others have adopted his name, attempting to share in the prestige.

Scholars have long seen Webster's 1844 dictionary to be an important resource for reading poet Emily Dickinson's life and work; she once commented that the "Lexicon" was her "only companion" for years. One biographer said, "The dictionary was no mere reference book to her; she read it as a priest his breviary—over and over, page by page, with utter absorption."

In 1850 Blackie and Son in Glasgow published the first general dictionary of English that relied heavily upon pictorial illustrations integrated with the text. Its The Imperial Dictionary, English, Technological, and Scientific, Adapted to the Present State of Literature, Science, and Art; On the Basis of Webster's English Dictionary used Webster's for most of their text, adding some additional technical words that went with illustrations of machinery.

Vincent P. Bynack (1984) examines Webster in relation to his commitment to the idea of a unified American national culture that would stave off the decline of republican virtues and solidarity. Webster acquired his perspective on language from such theorists as Maupertuis, Michaelis, and Herder. There he found the belief that a nation's linguistic forms and the thoughts correlated with them shaped individuals' behavior. Thus, the etymological clarification and reform of American English promised to improve citizens' manners and thereby preserve republican purity and social stability. This presupposition animated Webster's Speller and Grammar.

Lepore (2008) demonstrates Webster's paradoxical ideas about language and politics and shows why Webster's endeavors were at first so poorly received. Culturally conservative Federalists denounced the work as radical—too inclusive in its lexicon and even bordering on vulgar. Meanwhile, Webster's old foes the Republicans attacked the man, labeling him mad for such an undertaking.

At age fourteen, his church pastor began tutoring him in Latin and Greek to prepare him for entering Yale College. Webster enrolled at Yale just before his 16th birthday, studying during his senior year with Ezra Stiles, Yale's President. His four years at Yale overlapped the American Revolutionary War and, because of food shortages and threatened British invasions, many of his classes had to be held in other towns. Webster served in the Connecticut Militia. His father had mortgaged the farm to send Webster to Yale, but he was now on his own and had nothing more to do with his family.