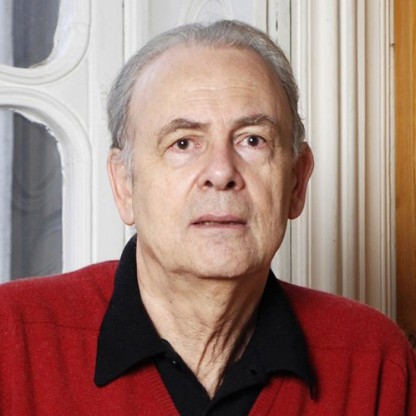

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Journalist & Author |

| Birth Day | June 19, 1924 |

| Birth Place | Union City, United States |

| Age | 96 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | November 30, 1990 |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

Net worth: $16 Million (2024)

Norman Cousins, a renowned journalist and author in the United States, has amassed an estimated net worth of $16 million by 2024. Throughout his career, Cousins has made significant contributions to the field of journalism, bringing insights and analysis through his thought-provoking writings. Known for his intellectual prowess and captivating storytelling, Cousins has become a prominent figure in both print and broadcast media. With numerous best-selling books to his name, he has not only garnered critical acclaim but also built a substantial fortune from his successful writing endeavors. Norman Cousins' remarkable net worth is a testament to his exceptional talent and the impact he has made on the literary world.

Biography/Timeline

Cousins attended Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx, New York City, graduating on February 3, 1933. He edited the high school paper, "The Square Deal," where his editing abilities were already in evidence. Cousins received a bachelor's degree from Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City.

He joined the staff of the New York Evening Post (now the New York Post) in 1934, and in 1935 was hired by Current History as a book critic. He later ascended to the position of managing Editor. He also befriended the staff of the Saturday Review of Literature (later renamed Saturday Review), which had its offices in the same building, and by 1940, joined the staff of that publication as well. He was named editor-in-chief in 1942, a position he would hold until 1972. Under his direction, circulation of the publication increased from 20,000 to 650,000.

Despite his role as an advocate of liberalism, he jokingly expressed opposition to women entering the workforce. In 1939, upon learning that the number of women in the workforce was close to the number of unemployed males, he offered this solution: “Simply fire the women, who shouldn’t be working anyway, and hire the men. Presto! No unemployment. No relief rolls. No depression.”

Politically, Cousins was a tireless advocate of liberal causes, such as nuclear disarmament and world peace, which he promoted through his writings in Saturday Review. In a 1984 forum at the University of California, Berkeley, titled "Quest for Peace", Cousins recalled the long editorial he wrote on August 6, 1945, the day the United States dropped the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. Titled "The Modern Man is Obsolete", Cousins, who stated that he felt "the deepest guilt" over the bomb's use on human beings, discussed in the editorial the social and political implications of the atomic bomb and nuclear power. He rushed to get it published the next day in the Review, and the response was considerable, as it was reprinted in newspapers around the country and enlarged into a book that was reprinted in different languages.

In the 1950s, Cousins played a prominent role in bringing the Hiroshima Maidens, a group of twenty-five Hibakusha, to the United States for medical treatment.

Cousins also wrote a collection of non-fiction books on the same subjects, such as the 1953 Who Speaks for Man? , which advocated a World Federation and nuclear disarmament. He also served as President of the World Federalist Association and chairman of the Committee for Sane Nuclear Policy, which in the 1950s warned that the world was bound for a nuclear holocaust if the threat of the nuclear arms race was not stopped. Cousins became an unofficial ambassador in the 1960s, and his facilitating communication between the Holy See, the Kremlin, and the White House helped lead to the Soviet-American test ban treaty, for which he was thanked by President John F. Kennedy and Pope John XXIII, the latter of whom awarded him his personal medallion. Cousins was also awarded the Eleanor Roosevelt Peace Award in 1963, the Family Man of the Year Award in 1968, the United Nations Peace Medal in 1971, the Niwano Peace Prize and the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism, both in 1990. He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1972 to 1975.

In the 1960s, he began the American-Soviet Dartmouth Conferences for peace process.

Cousins joined the University of California, Los Angeles faculty in 1978 and became an adjunct professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Science. He taught ethics and medical literature. His research interest was the connection between attitude and health.

Later in life he and his wife Ellen together fought his heart disease, again with exercise, a daily regimen of vitamins, and with the good nutrition provided by Ellen's organic garden. He wrote a collection of best-selling non-fiction books on illness and healing, as well as a 1980 autobiographical memoir, Human Options: An Autobiographical Notebook.

Cousins was portrayed by actor Ed Asner in a 1984 television movie, Anatomy of an Illness, which was based on Cousins's 1979 book, Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient: Reflections on Healing. Cousins was not pleased with the commercial nature of the movie, and with Hollywood's sensationalistic exaggerations of his experience. He and other members of the Cousins family were also taken aback by the casting of Asner, due to the fact that the two men bore scant physical resemblance to each other. But Asner tried faithfully, Cousins felt, to convey the spirit of his subject, and once the film was completed, Cousins was said by Asner to look upon the movie with a certain degree of tolerance, if not with delight.

An obituary containing further information, mainly of his writing and editing career, was published by the December 2, 1990 edition of The New York Times.

Cousins did research on the biochemistry of human emotions, which he long believed were the key to human beings’ success in fighting illness. It was a belief he maintained even as he battled in 1964 a sudden-onset case of a crippling connective tissue disease, which was also referred to as a collagen disease. Experts at Dr. Rusk's rehabilitation clinic confirmed this diagnosis and added a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. Told that he had one chance in 500 of recovery, Cousins developed his own recovery program. He took massive intravenous doses of Vitamin C and had self-induced bouts of laughter brought on by films of the television show Candid Camera, and by various comic films. His positive attitude was not new to him, however. He had always been an optimist, known for his kindness to others, and his robust love of life itself. "I made the joyous discovery that ten minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep," he reported. "When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval." His struggle with that illness is detailed in his 1979 book Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient.