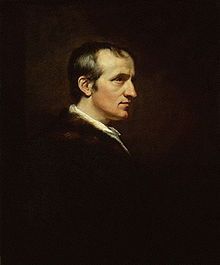

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Poet |

| Birth Day | August 04, 1792 |

| Birth Place | England, British |

| Age | 227 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 8 July 1822(1822-07-08) (aged 29)\nGulf of La Spezia, Kingdom of Sardinia (now Italy) |

| Birth Sign | Virgo |

| Occupation | Poet, dramatist, essayist, novelist |

| Alma mater | University College, Oxford (no degree) |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Spouse | Harriet Westbrook (m. 1811; d. 1816) Mary Shelley (m. 1816) |

Net worth

Percy Bysshe Shelley, commonly referred to as P B Shelley, was a renowned British poet known for his innovative and profound works during the Romantic era. As a highly regarded literary figure, his contributions to the world of poetry have left a lasting impact. With his talent and influence, it is estimated that P B Shelley's net worth will be between $100K and $1 million by the year 2024. His remarkable poetic skills and significant contributions to British literature have rightfully earned him the recognition and financial success he deserves.

Famous Quotes:

On one occasion I had to fetch or take to Byron some copy for the paper which my father, himself and Shelley, jointly conducted. I found him seated on a lounge feasting himself from a drum of figs. He asked me if I would like a fig. Now, in that, Leno, consists the difference, Shelley would have handed me the drum and allowed me to help myself.

Biography/Timeline

Henry Shelley became father to younger Henry Shelley. This younger Henry had at least three sons. The youngest of them, Richard Shelley was born in 1583, and baptized 17 November 1583 in Warminghurst, Sussex, England. Richard later married on 3 February 1601 in Itchingfield to Jonne (aka Joane) Feste/Feest/Fuste, daughter of John Feest/Fuste from Itchingfield, near Horsham, West Sussex. Their grandson, John Shelley of Fen Place, Turners Hill, West Sussex, was married himself to Helen Bysshe, daughter of Roger Bysshe. Their son Timothy Shelley of Fen Place (born c. 1700) married widow Johanna Plum from New York City. Timothy and Johanna were the great-grandparents of Percy.

Percy was born to Sir Timothy Shelley (7 September 1753 – 24 April 1844) and his wife Elizabeth Pilfold following their marriage in October 1791. His father was son and heir to Sir Bysshe Shelley, 1st Baronet of Castle Goring (21 June 1731 – 6 January 1815) by his wife Mary Catherine Michell (d. 7 November 1760). His mother was daughter of Charles Pilfold of Effingham. Through his paternal grandmother, Percy was a great-grandson to Reverend Theobald Michell of Horsham. Through his maternal lineage, he was a cousin of Thomas Medwin—a childhood friend and Shelley's biographer.

Shelley was born on 4 August 1792 at Field Place, Broadbridge Heath, near Horsham, West Sussex, England. He was the eldest legitimate son of Sir Timothy Shelley (1753–1844), a Whig Member of Parliament for Horsham from 1790–92 and for Shoreham between 1806–12, and his wife, Elizabeth Pilfold (1763–1846), a Sussex landowner. He had four younger sisters and one much younger brother. He received his early education at home, tutored by the Reverend Evan Edwards of nearby Warnham. His cousin and lifelong friend Thomas Medwin, who lived nearby, recounted his early childhood in his The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. It was a happy and contented childhood spent largely in country pursuits such as fishing and hunting.

In 1802 he entered the Syon House Academy of Brentford, Middlesex. In 1804, Shelley entered Eton College, where he fared poorly, and was subjected to an almost daily mob torment at around noon by older boys, who aptly called these incidents "Shelley-baits". Surrounded, the young Shelley would have his books torn from his hands and his clothes pulled at and torn until he cried out madly in his high-pitched "cracked soprano" of a voice. This daily misery could be attributed to Shelley's refusal to take part in fagging and his indifference towards games and other youthful activities. Because of these peculiarities he acquired the nickname "Mad Shelley". Shelley possessed a keen interest in science at Eton, which he would often apply to cause a surprising amount of mischief for a boy considered to be so sensible. Shelley would often use a frictional electric machine to charge the door handle of his room, much to the amusement of his friends. His friends were particularly amused when his gentlemanly tutor, Mr Bethell, in attempting to enter his room, was alarmed at the noise of the electric shocks, despite Shelley's dutiful protestations. His mischievous side was again demonstrated by "his last bit of naughtiness at school", which was to blow up a tree on Eton's South Meadow with gunpowder. Despite these jocular incidents, a contemporary of Shelley, W. H. Merie, recalled that Shelley made no friends at Eton, although he did seek a kindred spirit without success.

On 10 April 1810 he matriculated at University College, Oxford. Legend has it that Shelley attended only one lecture while at Oxford, but frequently read sixteen hours a day. His first publication was a Gothic novel, Zastrozzi (1810), in which he vented his early atheistic worldview through the villain Zastrozzi; this was followed at the end of the year by St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian: A Romance (dated 1811). In the same year, Shelley, together with his sister Elizabeth, published Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire and, while at Oxford, he issued a collection of verses (ostensibly burlesque but quite subversive), Posthumous Fragments of Margaret Nicholson, with Thomas Jefferson Hogg.

Four months after being sent down from Oxford, on 28 August 1811, the 19-year-old Shelley eloped to Scotland with the 16-year-old Harriet Westbrook, a pupil at the same boarding school as Shelley's sisters, whom his father had forbidden him to see. Harriet Westbrook had been writing Shelley passionate letters threatening to kill herself because of her unhappiness at the school and at home. Shelley, heartbroken after the failure of his romance with his cousin, Harriet Grove, cut off from his mother and sisters, and convinced he had not long to live, impulsively decided to rescue Westbrook and make her his beneficiary. Westbrook's 28-year-old sister Eliza, to whom Harriet was very close, appears to have encouraged the young girl's infatuation with the Future baronet. The Westbrooks pretended to disapprove but secretly encouraged the elopement. Sir Timothy Shelley, however, outraged that his son had married beneath him (Harriet's father, though prosperous, had kept a tavern), revoked Shelley's allowance and refused ever to receive the couple at Field Place. Harriet also insisted that her sister Eliza, whom Shelley detested, live with them. Shelley invited his friend Hogg to share his ménage but asked him to leave when Hogg made advances to Harriet. Shelley was also at this time increasingly involved in an intense platonic relationship with Elizabeth Hitchener, a 28-year-old unmarried schoolteacher of advanced views, with whom he had been corresponding. Hitchener, whom Shelley called the "sister of my soul" and "my second self", became his muse and confidante in the writing of his philosophical poem Queen Mab, a Utopian allegory.

Some believed his death was not accidental, that Shelley was depressed and wanted to die; others suggested he simply did not know how to navigate. More fantastical theories, including the possibility of pirates mistaking the boat for Byron's, also circulated. There is a small amount of material, though scattered and contradictory, suggesting that Shelley may have been murdered for political reasons: previously, at Plas Tan-Yr-Allt, the Regency house he rented at Tremadog, near Porthmadog, north-west Wales, from 1812 to 1813, he had allegedly been surprised and attacked during the night by a man who may have been, according to some later Writers, an intelligence agent. Shelley, who was in financial difficulty, left forthwith leaving rent unpaid and without contributing to the fund to support the house owner, william Madocks; this may provide another, more plausible explanation for this story.

In Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem (1813) he wrote about the change to a vegetarian diet: "And man ... no longer now/ He slays the lamb that looks him in the face,/ And horribly devours his mangled flesh."

On 28 July 1814 Shelley abandoned Harriet, now pregnant with their son Charles (November 1814 – 1826) and (in imitation of the hero of one of Godwin's novels) he ran away to Switzerland with Mary, then 16, inviting her stepsister Claire Clairmont (also 16) along because she could speak French. The older sister Fanny was left behind, to her great dismay, for she, too, had fallen in love with Shelley. The three sailed to Europe, and made their way across France to Switzerland on foot, reading aloud from the works of Rousseau, Shakespeare, and Mary's mother, Mary Wollstonecraft (an account of their travels was subsequently published by the Shelleys).

After six weeks, homesick and destitute, the three young people returned to England. The enraged william Godwin refused to see them, though he still demanded money, to be given to him under another name, to avoid scandal. In late 1815, while living in a cottage in Bishopsgate, Surrey, with Mary and avoiding creditors, Shelley wrote Alastor, or The Spirit of Solitude. It attracted little attention at the time, but has now come to be recognised as his first major achievement. At this point in his writing career, Shelley was deeply influenced by the poetry of Wordsworth.

After Shelley's and Mary's return to England, Fanny Imlay, Mary's half-sister and Claire's stepsister, despondent over her exclusion from the Shelley household and perhaps unhappy at being omitted from Shelley's will, travelled from Godwin's household in London to kill herself in Wales in early October. On 10 December 1816 the body of Shelley's estranged wife Harriet was found in an advanced state of pregnancy, drowned in the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London. Shelley had made generous provision for Harriet and their children in his will and had paid her a monthly allowance as had her father. It is thought that Harriet, who had left her children with her sister Eliza and had been living alone under the name of Harriet Smith, mistakenly believed herself to have been abandoned by her new lover, 36-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Maxwell, who had been deployed abroad, after a landlady refused to forward his letters to her. On 30 December 1816, barely three weeks after Harriet's body was recovered, Shelley and Mary Godwin were married. The marriage was intended partly to help secure Shelley's custody of his children by Harriet and partly to placate Godwin, who had coldly refused to speak to his daughter for two years, and who now received the couple. The courts, however, awarded custody of Shelley and Harriet's children to foster parents, on the grounds that Shelley was an atheist.

The Shelleys moved between various Italian cities during these years; in later 1818 they were living in Florence, in a pensione on the Via Valfonda. This street now runs alongside Florence's railway station, and the building now on the site, the original having been destroyed in World War II, carries a plaque recording the poet's stay. Here they received two visitors, a Miss Sophia Stacey and her much older travelling companion, Miss Corbet Parry-Jones (to be described by Mary as "an ignorant little Welshwoman"). Sophia had for three years in her youth been ward of the poet's aunt and uncle. The pair moved into the same pensione and stayed for about two months. During this period Mary gave birth to another son; Sophia is credited with suggesting that he be named after the city of his birth, so he became Percy Florence Shelley, later Sir Percy. Shelley also wrote his "Ode to Sophia Stacey" during this time. They then moved to Pisa, largely at the suggestion of its resident Margaret King, who, as a former pupil of Mary Wollstonecraft, took a maternal interest in the younger Mary and her companions. This "no nonsense grande dame" and her common-law husband George william Tighe inspired the poet with "a new-found sense of radicalism". Tighe was an agricultural theorist, and provided the younger man with a great deal of material on chemistry, biology and statistics.

Shelley completed Prometheus Unbound in Rome, and he spent mid-1819 writing a tragedy, The Cenci, in Leghorn (Livorno). In this year, prompted among other causes by the Peterloo Massacre, he wrote his best-known political poems: The Masque of Anarchy and Men of England. These were probably his best-remembered works during the 19th century. Around this time period, he wrote the essay The Philosophical View of Reform, which was his most thorough exposition of his political views to that date.

In 1820, hearing of John Keats's illness from a friend, Shelley wrote him a letter inviting him to join him at his residence at Pisa. Keats replied with hopes of seeing him, but instead, arrangements were made for Keats to travel to Rome with the Artist Joseph Severn. Inspired by the death of Keats, in 1821 Shelley wrote the elegy Adonais.

In 1821 Shelley met Edward Ellerker Williams, a British naval officer, and his wife Jane Williams. Shelley developed a very strong affection towards Jane and addressed a number of poems to her. In the poems addressed to Jane, such as With a Guitar, To Jane and One Word is Too Often Profaned, he elevates her to an exalted position worthy of worship.

On 8 July 1822, less than a month before his thirtieth birthday, Shelley drowned in a sudden storm on the Gulf of Spezia while returning from Leghorn (Livorno) to Lerici in his sailing boat, the Don Juan. He was returning from having set up The Liberal with the newly arrived Leigh Hunt. The name Don Juan, a compliment to Byron, was chosen by Edward John Trelawny, a member of the Shelley–Byron Pisan circle. However, according to Mary Shelley's testimony, Shelley changed it to Ariel, which annoyed Byron, who forced the painting of the words "Don Juan" on the mainsail. The vessel, an open boat, was custom-built in Genoa for Shelley. It did not capsize but sank; Mary Shelley declared in her "Note on Poems of 1822" (1839) that the design had a defect and that the boat was never seaworthy. In fact the Don Juan was seaworthy; the sinking was due to a severe storm and poor seamanship of the three men on board.

Three children survived Shelley: Ianthe and Charles, his daughter and son by Harriet; and Percy Florence Shelley, his son by Mary. Charles, who suffered from tuberculosis, died in 1826 after being struck by lightning during a rainstorm. Percy Florence, who eventually inherited the baronetcy in 1844, died without children "of his body", as the old legal phrase went.

In other countries such as India, Shelley's works both in the original and in translation have influenced poets such as Rabindranath Tagore and Jibanananda Das. A pirated copy of Prometheus Unbound dated 1835 is said to have been seized in that year by customs at Bombay.

The only lineal descendants of the poet are therefore the children of Ianthe. Ianthe Eliza Shelley was married in 1837 to Edward Jeffries Esdaile of Cothelstone Manor, grandson of the banker william Esdaile of Lombard Street, London. The marriage resulted in the birth of three daughters, Ianthe Harriet Shelley (1839–1849), Eliza Margaret (1841–1930), and Mary Emily Sydney (1848–1854), and three sons, Charles Edward (1842–1842), Charles Edward Jeffries (1845–1922), and william (1846–1915). Ianthe died in 1876, and her only descendants result from the marriage of Charles Edward Jeffries Esdaile and Marion Maxwell Sandbach.

Shelley's widow Mary bought a cliff-top home at Boscombe, Bournemouth, in 1851. She intended to live there with her son, Percy, and his wife Jane, and had the remains of her own parents moved from their London burial place at St Pancras Old Church to an underground mausoleum in the town. The property is now known as Shelley Manor. When Lady Jane Shelley was to be buried in the family vault, it was discovered that in her copy of Adonaïs was an envelope containing ashes, which she had identified as belonging to her father-in-law. The family had preserved the story that when Shelley's body had been burned, his friend Edward Trelawny had snatched the whole heart from the pyre. These same accounts claim that the heart had been buried with Shelley's son, Percy. All accounts agree, however, that the remains now lie in the vault in the churchyard of St Peter's Church, Bournemouth.

Shelley's body was washed ashore and later, in keeping with quarantine regulations, was cremated on the beach near Viareggio. In Shelley's pocket was a small book of Keats' poetry. Upon hearing this, Byron (never one to give compliments) said of Shelley: "I never met a man who wasn't a beast in comparison to him" . The day after the news of his death reached England, the Tory newspaper The Courier printed: "Shelley, the Writer of some infidel poetry, has been drowned; now he knows whether there is God or no." A reclining statue of Shelley's body, depicted as washed up on the shore, created by Sculptor Edward Onslow Ford at the behest of Shelley's daughter-in-law, Jane, Lady Shelley, is the centrepiece of the Shelley Memorial at University College, Oxford. An 1889 painting by Louis Édouard Fournier, The Funeral of Shelley (also known as The Cremation of Shelley), contains inaccuracies. In pre-Victorian times it was English custom that women would not attend funerals for health reasons. Mary Shelley did not attend but was featured in the painting, kneeling at the left-hand side. Leigh Hunt stayed in the carriage during the ceremony but is also pictured. Also, Trelawny, in his account of the recovery of Shelley's body, records that "the face and hands, and parts of the body not protected by the dress, were fleshless," and by the time that the party returned to the beach for the cremation, the body was even further decomposed. In his graphic account of the cremation, he writes of Byron being unable to face the scene, and withdrawing to the beach.

Several members of the Scarlett family were born at Percy Florence's seaside home "Boscombe Manor" in Bournemouth. They were descendants of Percy Florence's and Jane Gibson's adopted daughter, Bessie Florence Gibson. The 1891 census shows Lady Jane Shelley, Percy Florence Shelley's widow, living at Boscombe Manor with several great-nephews. Percy Florence Shelley died in 1889, and his widow, the former Jane St. John (born Gibson), died in 1899.

Many of Shelley's works remained unpublished or little known after his death, with longer pieces such as A Philosophical View of Reform existing only in manuscript until the 1920s. This contributed to the Victorian idea of him as a minor lyricist. With the inception of formal literary studies in the early twentieth century and the slow rediscovery and re-evaluation of his oeuvre by scholars such as Kenneth Neill Cameron, Donald H. Reiman, and Harold Bloom, the modern idea of Shelley could not be more different.

For several years in the 20th century some of Trelawny's collection of Shelley ephemera, including a painting of Shelley as a child, a jacket, and a lock of his hair, were on display in "The Shelley Rooms", a small museum at Shelley Manor. When the museum finally closed in 2001, these items were returned to Lord Abinger, who descends from a niece of Lady Jane Shelley.

In 2005 the University of Delaware Press published an extensive two-volume biography by James Bieri. In 2008 the Johns Hopkins University Press published Bieri's 856-page one-volume biography, Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography.

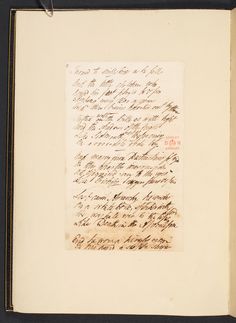

The rediscovery in mid-2006 of Shelley's long-lost Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things, as noted above, was slow to be followed up until the only known surviving copy was acquired by the Bodleian Library in Oxford as its 12-millionth book in November 2015 and made available online. An analysis of the poem by the only person known to have examined the whole work at the time of the original discovery appeared in the Times Literary Supplement: H. R. Woudhuysen, "Shelley's Fantastic Prank", 12 July 2006.

In 2007 John Lauritsen published The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein, in which he argued that Percy Bysshe Shelley's contributions to the novel were much more extensive than had previously been assumed. It has been known and not disputed that Shelley wrote the Preface – although uncredited – and that he contributed at least 4,000–5,000 words to the novel. Lauritsen sought to show that Shelley was the primary author of the novel.

In 2008 Percy Bysshe Shelley was credited as the co-author of Frankenstein by Charles E. Robinson in a new edition of the novel entitled The Original Frankenstein published by the Bodleian Library in Oxford and by Random House in the US. Robinson determined that Percy Bysshe Shelley was the co-author of the novel: "He made very significant changes in words, themes and style. The book should now be credited as 'by Mary Shelley with Percy Shelley'."

During this period, Shelley travelled to Keswick in England's Lake District, where he visited the poet Robert Southey, under the mistaken impression that Southey was still a political radical. Southey, who had himself been expelled from the Westminster School for opposing flogging, was taken with Shelley and predicted great things for him as a poet. He also informed Shelley that william Godwin, author of Political Justice, which had greatly influenced him in his youth, and which Shelley also admired, was still alive. Shelley wrote to Godwin, offering himself as his devoted disciple and informing Godwin that he was "the son of a man of fortune in Sussex" and "heir by entail to an estate of 6,000 £ per an." Godwin, who supported a large family and was chronically penniless, immediately saw in Shelley a source of his financial salvation. He wrote asking for more particulars about Shelley's income and began advising him to reconcile with Sir Timothy. Meanwhile, Sir Timothy's patron, the Duke of Norfolk, a former Catholic who favoured Catholic Emancipation, was also vainly trying to reconcile Sir Timothy and his son, whose political career the Duke wished to encourage. A maternal uncle ultimately supplied money to pay Shelley's debts, but Shelley's relationship with the Duke may have influenced his decision to travel to Ireland. In Dublin, Shelley published his Address to the Irish People, priced at fivepence, "the lowest possible price" to "awaken in the minds of the Irish poor a knowledge of their real state, summarily pointing out the evils of that state and suggesting a rational means of remedy – Catholic Emancipation and a repeal of the Union Act" (the latter "the most successful engine that England ever wielded over the misery of fallen Ireland"). His activities earned him the unfavourable attention of the British government.

In late 2014 Shelley's work led lecturers from the University of Pennsylvania and New York University to produce a Massive open online course (MOOC) on the life of Percy Shelley and Prometheus Unbound.