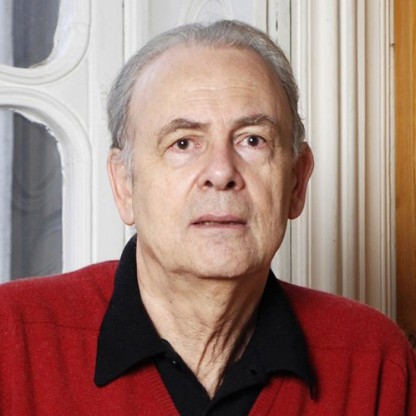

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | American writer |

| Birth Day | June 26, 1892 |

| Birth Place | Hillsboro, United States |

| Age | 127 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | March 6, 1973(1973-03-06) (aged 80)\nDanby, Vermont, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Occupation | Writer, Teacher |

| Subject | English |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize 1932 Nobel Prize in Literature 1938 |

| Spouse | John Lossing Buck (1917–1935) Richard J. Walsh (1935–1960) until his death |

| Traditional Chinese | 賽珍珠 |

| Simplified Chinese | 赛珍珠 |

| Literal meaning | Precious Pearl |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinWade–GilesIPA | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Sài Zhēnzhū Wade–Giles Sai Chen-chu IPA [saɪ˥˩ tʂən˥ tʂu˥] Sài ZhēnzhūSai Chen-chu[saɪ˥˩ tʂən˥ tʂu˥] |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Sài Zhēnzhū |

| Wade–Giles | Sai Chen-chu |

| IPA | [saɪ˥˩ tʂən˥ tʂu˥] |

Net worth

Pearl Buck, widely recognized as an accomplished American writer, is anticipated to possess a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in the year 2024. With her exceptional literary contributions and numerous best-selling novels, Buck has garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success throughout her career. Known for her insightful portrayals of Chinese culture in her works, she became the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1938. Pearl Buck's impact on literature and her remarkable financial achievements solidify her position as one of the leading American writers of her time.

Biography/Timeline

Originally named Comfort by her parents, Pearl Sydenstricker was born in Hillsboro, West Virginia, to Caroline Stulting (1857–1921) and Absalom Sydenstricker. Her parents, Southern Presbyterian missionaries, traveled to China soon after their marriage on July 8, 1880, but returned to the United States for Pearl's birth. When Pearl was five months old, the family arrived in China, first in Huai'an and then in 1896 moved to Zhenjiang (then often known as Jingjiang or, in the postal, Tsingkiang), near Nanking.

Of her siblings who survived into adulthood, Edgar Sydenstricker (1881–1936) had a distinguished career in epidemiology as an official with the Milbank Memorial Fund and Grace Sydenstricker Yaukey (1899–1994) was a Writer who wrote young adult books and books about Asia under the pen name Cornelia Spencer.

Pearl Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973; also known by her Chinese name Sai Zhenzhu; Chinese: 賽珍珠) was an American Writer and Novelist. As the daughter of missionaries, Buck spent most of her life before 1934 in Zhenjiang, China. Her novel The Good Earth was the best-selling fiction book in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932. In 1938, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces". She was the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In 1911, Pearl left China to attend Randolph-Macon Woman's College in Lynchburg, Virginia, in the United States, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1914 and a member of Kappa Delta Sorority. Although she had not intended to return to China, much less become a missionary, she quickly applied to the Presbyterian Board when her Father wrote that her mother was seriously ill. From 1914 to 1932, she served as a Presbyterian missionary, but her views later became highly controversial during the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy, leading to her resignation.

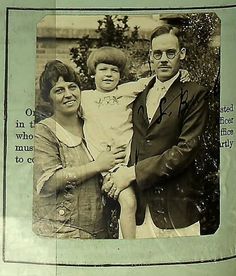

In 1914, Pearl returned to China. She married an agricultural Economist missionary, John Lossing Buck, on May 30, 1917, and they moved to Suzhou, Anhui Province, a small town on the Huai River (not to be confused with the better-known Suzhou in Jiangsu Province). This region she describes in her books The Good Earth and Sons.

The tragedies and dislocations that Buck suffered in the 1920s reached a climax in March 1927, during the "Nanking Incident". In a confused battle involving elements of Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist troops, Communist forces, and assorted Warlords, several Westerners were murdered. Since her Father Absalom insisted, as he had in 1900 in the face of the Boxers, the family decided to stay in Nanjing until the battle reached the city. When violence broke out, a poor Chinese family invited them to hide in their hut while the family house was looted. The family spent a day terrified and in hiding, after which they were rescued by American gunboats. They traveled to Shanghai and then sailed to Japan, where they stayed for a year, after which they moved back to Nanjing. Pearl later said that this year in Japan showed her that not all Japanese were militarists. When she returned from Japan in late 1927, Pearl devoted herself in earnest to the vocation of writing. Friendly relations with prominent Chinese Writers of the time, such as Xu Zhimo and Lin Yutang, encouraged her to think of herself as a professional Writer. She wanted to fulfill the ambitions denied to her mother, but she also needed money to support herself if she left her marriage, which had become increasingly lonely, and since the mission board could not provide it, she also needed money for Carol’s specialized care. Pearl went once more to the States in 1929 to find long-term care for Carol, and while there, Richard J. Walsh, Editor at John Day publishers in New York, accepted her novel East Wind: West Wind. She and Richard began a relationship that would result in marriage and many years of professional teamwork. Back in Nanking, she retreated every morning to the attic of her university bungalow and within the year completed the manuscript for The Good Earth.

She was involved in the charity relief campaign for the victims of the 1931 China floods, writing a series of short stories describing the plight of refugees, which were broadcast on the radio in the United States and later published in her collected volume The First Wife and Other Stories. In 1949, outraged that existing adoption services considered Asian and mixed-race children unadoptable, Buck co-founded Welcome House, Inc., the first international, interracial adoption agency, along with James A. Michener, Oscar Hammerstein II and his second wife Dorothy Hammerstein. In nearly five decades of work, Welcome House has placed over five thousand children. In 1964, to support kids who were not eligible for adoption, Buck established the Pearl S. Buck Foundation (now called Pearl S. Buck International) to "address poverty and discrimination faced by children in Asian countries". In 1964, she opened the Opportunity Center and Orphanage in South Korea, and later offices were opened in Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam. When establishing Opportunity House, Buck said, "The purpose...is to publicize and eliminate injustices and prejudices suffered by children, who, because of their birth, are not permitted to enjoy the educational, social, economic and civil privileges normally accorded to children."

When John Lossing Buck took the family to Ithaca the next year, Pearl accepted an invitation to address a luncheon of Presbyterian women at the Astor Hotel in New York City. Her talk was titled “Is There a Case for the Foreign Missionary?” and her answer was a barely qualified “no”. She told her American audience that she welcomed Chinese to share her Christian faith, but argued that China did not need an institutional church dominated by missionaries who were too often ignorant of China and arrogant in their attempts to control it. When the talk was published in Harper's magazine, the scandalized reaction led Pearl to resign her position with the Presbyterian Board. In 1934, Pearl left China, believing she would return, while John Lossing Buck remained.

Many contemporary reviewers were positive and praised her "beautiful prose", even though her "style is apt to degenerate into over-repetition and confusion". Robert Benchley wrote a parody of The Good Earth that focused on just these qualities. Peter Conn, in his biography of Buck, argues that despite the accolades awarded to her, Buck's contribution to literature has been mostly forgotten or deliberately ignored by America's cultural gatekeepers. Kang Liao argues that Buck played a "pioneering role in demythologizing China and the Chinese people in the American mind". Phyllis Bentley, in an overview of Buck's work published in 1935, was altogether impressed: "But we may say at least that for the interest of her chosen material, the sustained high level of her technical skill, and the frequent universality of her conceptions, Mrs. Buck is entitled to take rank as a considerable Artist. To read her novels is to gain not merely knowledge of China but wisdom about life." These works aroused considerable popular sympathy for China, and helped foment poor relations with Japan.

In 1938 the Nobel Prize committee in awarding the prize said:

In the mid 1960s, Buck increasingly came under the influence of Theodore Harris, a former dance instructor, who became her confidant, co-author, and financial advisor. She soon depended on him for all her daily routines, and placed him in control of Welcome House and the Pearl S. Buck Foundation. Harris, who was given a lifetime salary as head of the foundation, created a scandal for Buck when he was accused of mismanaging the foundation, diverting large amounts of the foundation's funds for his friends' and his own personal expenses, and treating staff poorly. Buck defended Harris, stating that he was "very brilliant, very high strung and artistic". Before her death Buck signed over her foreign royalties and her personal possessions to Creativity Inc., a foundation controlled by Harris, leaving her children a relatively small percentage of her estate.

During the Cultural Revolution, Buck, as a preeminent American Writer of Chinese village life, was denounced as an "American cultural imperialist". Buck was "heartbroken" when she was prevented from visiting China with Richard Nixon in 1972. Her 1962 novel Satan Never Sleeps described the Communist tyranny in China. Following the Communist Revolution in 1949, Buck was repeatedly refused all attempts to return to her beloved China and therefore was compelled to remain in the United States for the rest of her life.

Buck died on March 6, 1973, from lung cancer. After her death, Buck's children contested the will and accused Harris of exerting "undue influence" on Buck during the last few years. Harris failed to appear at trial and the court ruled in the family's favor.

Buck was honored in 1983 with a 5¢ Great Americans series postage stamp issued by the United States Postal Service In 1999 she was designated a Women's History Month Honoree by the National Women's History Project.

Chinese-American author Anchee Min said she "broke down and sobbed" after reading The Good Earth for the first time as an adult, which she had been forbidden to read growing up in China during the Cultural Revolution. Min said Buck portrayed the Chinese peasants "with such love, affection and humanity" and it inspired Min's novel Pearl of China (2010), a fictional biography about Buck.