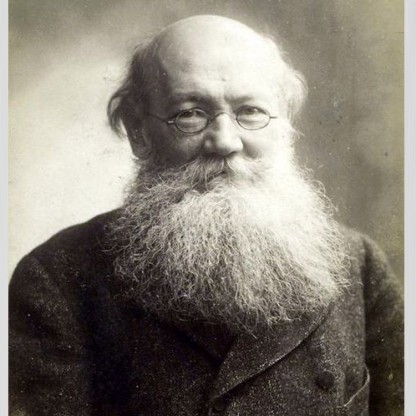

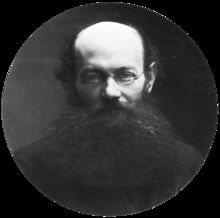

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Philosopher & Activist |

| Birth Day | December 09, 1842 |

| Birth Place | Moscow, Russian Empire, Russian |

| Age | 177 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | February 8, 1921(1921-02-08) (aged 78)\nDmitrov, Russian SFSR |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University (no degree) |

| Spouse(s) | Sofia Ananyeva-Rabinovich |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy Western philosophy |

| School | Anarcho-communism |

| Main interests | Authority Cooperation Politics Revolution Labor Economics Agriculture Evolution Geography Literature Science Philosophy Ethics |

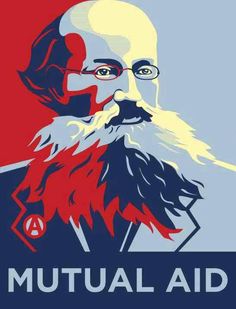

| Notable ideas | Founder of anarcho-communism Mutual aid Abolition of wage-labor Four-hour workday Voluntary communes The Conquest of Bread Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution Fields, Factories and Workshops |

Net worth

Peter Kropotkin, the prominent philosopher and activist hailing from Russia, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million by the year 2024. Known for his contributions to anarchist theory and his strong advocacy for societal cooperation and mutual aid, Kropotkin's ideals have made a lasting impact on the field of political philosophy. Despite passing away in 1921, his legacy as a pioneering thinker continues to resonate with many activists and scholars around the world. His net worth serves as a testament to the enduring value and influence of his ideas.

Famous Quotes:

In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavourable to the species. The animal species[...] in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits[...] and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development[...] are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.

— Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Conclusion.

Biography/Timeline

The administrator under whom Kropotkin served, General Boleslar Kazimirovich Kukel (1829–1869) was a liberal and a democrat who maintained personal connections to various Russian radical political figures exiled to Siberia. These included the Writer M. I. Mikhailov (1826–1865), to whom Kukel sent Kropotkin to warn the exiled intellectual that Moscow police agents were on the scene to examine his ongoing political activities in confinement. As a result of this assignment, Kropotkin made the acquaintance of Mikhailov, who provided the young Tsarist functionary with a copy of a book by the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon — Kropotkin's first introduction to anarchist ideas. Kukel was subsequently dismissed from his administrative position and Kropotkin moved from administration to state-sponsored scientific endeavors.

In 1857, at age 14, Kropotkin enrolled in the Corps of Pages at St. Petersburg. Only 150 boys – mostly children of nobility belonging to the court – were educated in this privileged corps, which combined the character of a military school endowed with special rights and of a court institution attached to the Imperial Household. Kropotkin's memoirs detail the hazing and other abuse of pages for which the Corps had become notorious.

In Moscow, Kropotkin developed what would become a lifelong interest in the condition of the peasantry. Although his work as a page for Tsar Alexander II made Kropotkin skeptical about the tsar's "liberal" reputation, Kropotkin was greatly pleased by the tsar's decision to emancipate the serfs in 1861. In St. Petersburg, he read widely on his own account, and gave special attention to the works of the French encyclopædists and to French history. The years 1857–1861 witnessed a growth in the intellectual forces of Russia, and Kropotkin came under the influence of the new liberal-revolutionary literature, which largely expressed his own aspirations.

In 1862, Kropotkin graduated first in his class from the Corps of Pages, and entered the Tsarist army. The members of the corps had the prescriptive right to choose the regiment to which they would be attached. Following a Desire to "be someone useful," Kropotkin chose the difficult route of serving in a Cossack regiment in eastern Siberia. For some time, he was aide de camp to the governor of Transbaikalia at Chita. Later he was appointed attaché for Cossack affairs to the governor-general of East Siberia at Irkutsk.

In 1864 Kropotkin accepted a position in a geographical survey expedition, crossing North Manchuria from Transbaikalia to the Amur, and soon was attached to another expedition up the Sungari River into the heart of Manchuria. The expeditions yielded valuable geographical results. The impossibility of obtaining any real administrative reforms in Siberia now induced Kropotkin to devote himself almost entirely to scientific exploration, in which he continued to be highly successful.

In 1867, Kropotkin resigned his commission in the army and returned to St. Petersburg, where he entered the Saint Petersburg Imperial University to study mathematics, becoming at the same time secretary to the geography section of the Russian Geographical Society. His departure from a family tradition of military Service prompted his father to disinherit him, "leaving him a 'prince' with no visible means of support".

In 1871, Kropotkin explored the glacial deposits of Finland and Sweden for the Society. In 1873, he published an important contribution to science, a map and paper in which he showed that the existing maps entirely misrepresented the physical features of Asia; the main structural lines were in fact from southwest to northeast, not from north to south or from east to west as had been previously supposed. During this work, he was offered the secretaryship of the Society, but he had decided that it was his duty not to work at fresh discoveries but to aid in diffusing existing knowledge among the people at large. Accordingly, he refused the offer and returned to St. Petersburg, where he joined the revolutionary party.

In 1872, Kropotkin was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress for subversive political activity, as a result of his work with the Circle of Tchaikovsky. Because of his aristocratic background, he received special privileges in prison, such as permission to continue his geographical work in his cell. He delivered his report on the subject of the Ice Age in 1876, where he argued that it had taken place in not as distant a past as originally thought.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, he attended a military school and later served as an officer in Siberia, where he participated in several geological expeditions. He was imprisoned for his activism in 1874 and managed to escape two years later. He spent the next 41 years in exile in Switzerland, France (where he was imprisoned for almost four years) and in England. He returned to Russia after the Russian Revolution in 1917, but was disappointed by the Bolshevik form of state socialism.

In 1876, just before his trial, Kropotkin was moved to a low-security prison in St. Petersburg, from which he escaped with the help of his friends. On the night of the escape, Kropotkin and his friends celebrated by dining in one of the finest restaurants in St. Petersburg, assuming correctly that the police would not think to look for them there. After this, he boarded a boat, and headed to England. After a short stay there, he moved to Switzerland where he joined the Jura Federation. In 1877, he moved to Paris, where he helped start the socialist movement. In 1878, he returned to Switzerland where he edited the Jura Federation's revolutionary newspaper Le Révolté, and published various revolutionary pamphlets.

In 1881, shortly after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, he was expelled from Switzerland. After a short stay at Thonon (Savoy), he stayed in London for nearly a year. He attended the Anarchist Congress in London from July 14, 1881. Other delegates included Marie Le Compte, Errico Malatesta, Saverio Merlino, Louise Michel, Nicholas Tchaikovsky and Émile Gautier. While respecting "complete autonomy of local groups", the congress defined propaganda actions that all could follow and agreed that propaganda by the deed was the path to social revolution. The Radical of July 23, 1881 reported that the congress met on July 18 at the Cleveland Hall, Fitzroy Square, with speeches by Marie Le Compte, "the transatlantic agitator", Louise Michel, and Kropotkin. Later Le Compte and Kropotkin gave talks to the Homerton Social Democratic Club and to the Stratford Radical and Dialectical Club.

Kropotkin returned to Thonon in late 1882. Soon he was arrested by the French government, tried at Lyon, and sentenced by a police-court magistrate (under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune) to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the IWA (1883). The French Chamber repeatedly agitated on his behalf, and he was released in 1886. He was invited to Britain by Charlotte Wilson, with whom he co-founded the Freedom Press, an anarchist newspaper which continues to this day. Kropotkin was a regular contributor. He settled near London, living at various times in Harrow, then Bromley, where his daughter and only child, Alexandra, was born on April 15, 1887. He also lived for a number of years in Brighton. While living in London, Kropotkin became friends with a number of prominent English-speaking socialists, including william Morris and George Bernard Shaw.

In his 1892 book The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He believed that should a society be socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services required by it, then no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange will prevent everyone to take what they need from the social product. He supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens of exchange for goods and services.

In 1902, Kropotkin published his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which provided an alternative view of animal and human survival, beyond the claims of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy proffered at the time by some "social Darwinists" such as Francis Galton. He argued that "it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human". Kropotkin explored the widespread use of cooperation as a survival mechanism in human societies - through their many stages - and among animals. He used many real-life examples in an attempt to show that the main factor in facilitating evolution is cooperation between individuals in free-associated societies and groups, without central control, authority, or compulsion. He did so in order to counteract the concept of fierce competition as the core of evolution, which concept provided a rationalization for the dominant political, economic, and social theories of the time and for the prevalent interpretations of Darwinism. In the last chapter, he wrote:

In 1917, after the February Revolution, Kropotkin returned to Russia after 40 years of exile. His arrival was greeted by cheering crowds of tens of thousands of people. He was offered the ministry of education in the Provisional Government, which he promptly refused, feeling that working with them would be a violation of his anarchist principles.

Kropotkin died of pneumonia on February 8, 1921, in the city of Dmitrov, and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. Thousands of people marched in his funeral procession, including, with Vladimir Lenin's approval, anarchists carrying banners with anti-Bolshevik slogans. It was to become the last public demonstration of anarchists, which saw engaged speeches by Emma Goldman and Aron Baron. In some versions of Peter Kropotkin's Conquest of Bread, it states in his mini biography, that this would be the last time that Kropotkin's supporters would be allowed to freely rally in public.

In 1957, the Dvorets Sovetov station of the Moscow Metro was renamed Kropotkinskaya in his honor.

Kropotkin's focus on local production led to his view that a country should strive for self-sufficiency – manufacture its own goods and grow its own food, lessening dependence on imports. To these ends he advocated irrigation and greenhouses to boost local food production ability.