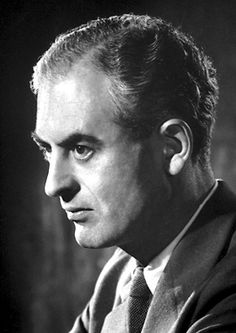

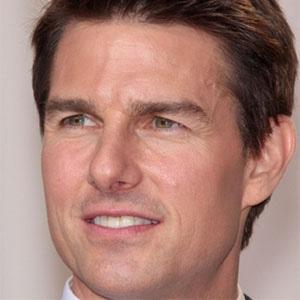

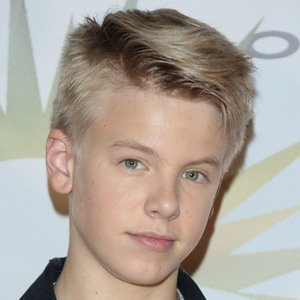

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Biologist |

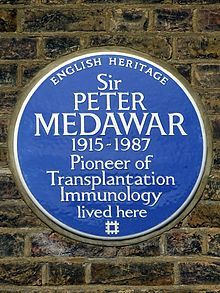

| Birth Day | February 28, 1915 |

| Birth Place | Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, British |

| Age | 105 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 2 October 1987(1987-10-02) (aged 72)\nLondon, England, United Kingdom |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Residence | England |

| Citizenship | British |

| Education | Marlborough College |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford (BA, DPhil) |

| Known for | Immunological tolerance Organ transplantation |

| Spouse(s) | Jean Medawar (née Taylor) (m. 1937) |

| Awards | FRS (1949) Royal Medal (1959) Nobel Prize (1960) EMBO Membership (1964) Copley Medal (1969) Kalinga Prize (1985) Faraday Prize (1987) |

| Fields | Zoology Immunology |

| Institutions | University of Birmingham University College London National Institute for Medical Research |

| Thesis | Growth promoting and growth inhibiting factors in normal and abnormal development (1941) |

| Doctoral students | Leslie Brent Avrion Mitchison |

| Other notable students | Rupert E. Billingham (postdoc) |

| Influences | Howard Florey J. Z. Young E.S. Goodrich A. J. Ayer Karl Popper |

Net worth

Peter Medawar, a renowned British biologist, is projected to have a net worth ranging from $100K to $1M in 2024. His expertise in the field of biology has garnered him global recognition and earned him a significant income. Throughout his career, Medawar has made groundbreaking contributions to the study of immunology and organ transplant, earning him numerous accolades including the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960. His extensive research and dedication to advancing scientific knowledge have undoubtedly contributed to his financial success.

Famous Quotes:

We obviously need a word for mere ageing, and I propose to use 'ageing' itself for just that purpose. 'Ageing' hereafter stands for mere ageing, and has no other innuendo. I shall use the word 'senescence' to mean ageing accompanied by that decline of bodily faculties and sensibilities and energies which ageing colloquially entails.

Biography/Timeline

Medawar was born on 28 February 1915, in Petrópolis (a town 40 miles north of Rio de Janeiro) in Brazil where his parents were living. He was the second child of Lebanese Nicholas Agnatius Medawar, born in the village of Jounieh, north of Beirut, Lebanon and British mother Edith Muriel (née Dowling). His Father, a Christian Maronite, became a naturalised British citizen and worked for a British dental supplies manufacturer that sent him to Brazil as an agent. (He later described his father's profession as selling "false teeth in South America".), His status as a British citizen was acquired at birth, as he said: "My birth was registered at the British Consulate in good time to acquire the status of 'natural-born British subject'." Medawar left Brazil with his family for England "towards the end of the war", and he lived there for the rest of his life. Peter was also a Brazilian citizen by Brazilian nationality law (jus soli), but renounced his citizenship to avoid military conscription required of Brazilian men.

In 1928, Medawar went to Marlborough College in Marlborough, Wiltshire He hated the college because "they were critical and querulous at the same time, wondering what kind of person a Lebanese was—something foreign you can be sure" and also because of its preference on Sports, in which he was weak. In 1932 he went on to Magdalen College, Oxford, graduating with a first-class honours degree in zoology in 1935. He was impressed and later influenced by his zoology Teacher John Z. Young who was also taught and inspired by one of his Marlborough teachers, who was barely literate but "a very, very good biology teacher".

Apart from his books on science and philosophy, it is interesting to note a short feature article on “Some Meistersinger Records” in the issue of The Gramophone for November 1930. The author was a P. B. Medawar. The evidence that this was indeed the Future Sir Peter Medawar—then a schoolboy of 15—was discussed in “Gramophone” in 1995 (“‘Gramophone’, Die Meistersinger and immunology”, by John E. Havard, December 1995).

Medawar was appointed Christopher Welch scholar and senior demy of Magdalen in 1935. He also worked at the Sir william Dunn School of Pathology supervised by Howard Florey (later Nobel laureate, and who inspired him to take up immunology) and was awarded his PhD in 1941.

Medawar married Jean Shinglewood Taylor on 27 February 1937. They met while in graduate class at Magdalen. Taylor approached him for the meaning of "heuristic", which she had to ask twice, and he had to finally offer lessons in philosophy. They had two sons, Charles and Alexander, and two daughters, Caroline and Louise. He never knew the exact meaning of his surname, an Arabic word, he was told, for "to make round"; but which a friend explained to him as "little round fat man".

Medawar's involvement with what became transplant research began during WWII, when he investigated possible improvements in skin grafts. His first publication on the subject was "Sheets of Pure Epidermal Epithelium from Human Skin", which was published in Nature in 1941. His studies particularly concerned solution for skin wounds among Soldiers in the war. In 1947 he moved to the University of Birmingham, taking along with him his PhD student Leslie Brent and postdoctoral fellow Rupert Billingham. His research became more focused in 1949, when Burnet, at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, advanced the hypothesis that during embryonic life and immediately after birth, cells gradually acquire the ability to distinguish between their own tissue substances on the one hand and unwanted cells and foreign material on the other.

Following his PhD, he was appointed a Rolleston Prizeman in 1942, senior research fellow of St John's College, Oxford in 1944, and a university demonstrator in zoology and comparative anatomy, also in 1944. He was elected Fellow of Magdalen by special election during 1938 to 1944 and 1946 to 1947. His Doctor of Philosophy thesis was approved, but the prohibitive cost of supplication meant he spent the money on his urgent appendectomy instead. The University of Oxford later awarded him a Doctor of Science degree in 1947.

Medawar was Mason professor of zoology at the University of Birmingham between 1947 and 1951. He became Jodrell professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at University College London in 1951. In 1962 he was appointed Director of the National Institute for Medical Research. His predecessor Sir Charles Harrington was an able administrator such that taking over his post was, as he described, "[N]o more strenuous than ... sliding over into the driving-seat of a Rolls-Royce". He was head of the transplantation section of the Medical Research Council's clinical research centre, Harrow, from 1971 to 1986. He became professor of experimental Medicine at the Royal Institution (1977–1983), and President of the Royal Postgraduate Medical School (1981–1987).

Medawar was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1949. With Frank Macfarlane Burnet he shared the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance". The British government conferred him a CBE in 1958, knighted him in 1965, and appointed him to the Order of the Companions of Honour in 1972, and Order of Merit in 1981. He was elected an EMBO Member in 1964 and received the Royal Medal in 1959, and the Copley Medal in 1969 both from the Royal Society. He was President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science during 1968–1969. He was awarded the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science in 1985. He was awarded a Honorary Doctor of Science Degree in 1961 by the University of Birmingham. He was elected a member of the American Society of Immunologists in 1971, and elected foreign member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1959, the American Philosophical Society in 1961, and the US National Academy of Sciences in 1965. Medawar has two awards named after him:

Medawar's 1951 lecture An unsolved Problem of biology (published 1952) addressed ageing and senescence, and he begins by defining both terms as follows:

In 1959 Medawar was invited by the BBC to present the broadcaster's annual Reith Lectures—following in the footsteps of his colleague, J. Z. Young, who was Reith Lecturer in 1950. For his own series of six radio broadcasts, titled The Future of Man, Medawar examined how the human race might continue to evolve.

Medawar was awarded his Nobel Prize in 1960 with Burnet for their work in tissue grafting which is the basis of organ transplants, and their discovery of acquired immunological tolerance. This work was used in dealing with skin grafts required after burns. Medawar's work resulted in a shift of emphasis in the science of immunology from one that attempts to deal with the fully developed immunity mechanism to one that attempts to alter the immunity mechanism itself, as in the attempt to suppress the body's rejection of organ transplants.

One of his best-known essays is his 1961 criticism of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's The Phenomenon of Man, of which he said: "Its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself".

While attending the annual British Association meeting in 1969, Medawar suffered a stroke when reading the lesson at Exeter Cathedral, a duty which falls on every new President of the British Association. It was, as he said, "monstrous bad luck because Jim Whyte Black had not yet devised beta-blockers, which slow the heart-beat and could have preserved my health and my career". Medawar’s failing health may have had repercussions for medical science and the relations between the scientific community and government. Before the stroke, Medawar was one of Britain's most influential Scientists, especially in the biomedical field.

After the impairment of his speech and movement, Medawar, with his wife's help, reorganised his life and continued to write and do research though on a greatly restricted scale. However, more haemorrhages followed and in 1987 he died in the Royal Free Hospital, London. He is buried—as is his wife Jean (1913–2005)—at Alfriston in East Sussex.