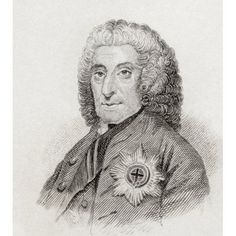

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | British Statesman |

| Birth Day | September 22, 1694 |

| Birth Place | London, British |

| Age | 325 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 24 March 1773 (1773-03-25) (aged 78) |

| Birth Sign | Libra |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Leicester |

| Spouse(s) | Melusina von der Schulenburg |

| Parents | Philip Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Chesterfield Lady Elizabeth Savile |

Net worth

Philip Dormer Stanhope Chesterfield, the esteemed British statesman, is projected to have a net worth ranging between $100,000 and $1 million in the year 2024. Known for his significant contributions to politics and diplomacy, Chesterfield's wealth reflects his successful career and financial prowess. With his astute decision-making skills and strategic endeavors, he has built a substantial fortune that places him among the upper echelons of society. As an influential figure in the British political landscape, Chesterfield's net worth attests to his accomplishments and the esteem in which he is held within the realm of British statesmanship.

Famous Quotes:

. . . However frivolous a company may be, still, while you are among them, do not show them, by your inattention, that you think them so; but rather take their tone, and conform in some degree to their weakness, instead of manifesting your contempt for them. There is nothing that people bear more impatiently, or forgive less, than contempt; and an injury is much sooner forgotten than an insult. If, therefore, you would rather please than offend, rather be well than ill spoken of, rather be loved than hated; remember to have that constant attention about you which flatters every man's little vanity; and the want of which, by mortifying his pride, never fails to excite his resentment, or at least his ill will. . .

Biography/Timeline

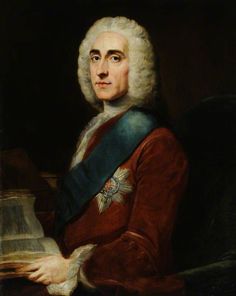

In the course of his post-graduate tour of Europe, the death of Queen Anne (r. 1702–14) and the accession of King George I (r. 1714–27) to the throne opened a political career for Stanhope, and he quickly returned to England. A member of the Whig party, Phillip Stanhope entered government Service as a courtier to the King, through the mentorship of his relative, James Stanhope, (later 1st Earl Stanhope), the King's favourite minister, who procured his appointment as Lord of the Bedchamber to the Prince of Wales, George II.

In 1715, Philip Dormer Stanhope entered the House of Commons as Lord Stanhope of Shelford and as member for St Germans. Later, when the impeachment of James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormonde came before the House, he used the occasion (5 August 1715) to try out the result of his rhetorical studies. His maiden speech was fluent and dogmatic, but upon its conclusion, another member -after first complimenting the speech- reminded the young orator that he was still six weeks short of his age of majority, and, consequently, was liable to a fine of £500 for speaking in the House; Lord Stanhope left the House of Commons with a low bow and set out for the Continent.

While in Paris, he sent the government valuable information about the developing Jacobite plot; and in 1716 he returned to Britain, resumed his seat, and became known as a skilled yet tactful debater. When King George I quarreled with his son, the Prince of Wales (George II) that same year, Lord Stanhope remained politically faithful to the Prince, while being careful not to break with the King's party." However, his continued friendly correspondence with the Prince's mistress -Henrietta Howard, later Countess of Suffolk- earned Chesterfield the personal hatred of the Prince's wife, Princess Caroline of Ansbach. In 1723 he was voted Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners. In January 1725, on the revival of the Order of the Bath, the red ribbon was offered to him, but Chesterfield declined the honour.

Upon his father's death in 1726, Lord Stanhope assumed his seat in the House of Lords and became the 4th Earl of Chesterfield. The new Lord Chesterfield's inclination towards oration -often seen as ineffective in the House of Commons due to its Polish and lack of force- was met with appreciation in the House of Lords, and won many to his side. In 1728, under Service to the new king, George II, Chesterfield was sent to the Hague as ambassador, where his gentle tact and linguistic dexterity served him well. As a reward for his diplomatic Service, Chesterfield received the Order of the Garter in 1730, the position of Lord Steward, and the friendship of Robert Walpole. While a British envoy in the Hague, he helped negotiate the second Treaty of Vienna (1731), which signaled the collapse of the Anglo-French Alliance, and the beginning of the Anglo-Austrian Alliance. In 1732, Madelina Elizabeth du Bouchet -a French governess- gave birth to his illegitimate son, Philip, for whose advice on life Chesterfield wrote the Letters to his Son. By the end of 1732, ill health and financial troubles led to Chesterfield's return to Britain and resignation as ambassador In 1731, while at The Hague, Chesterfield initiated the Grand Duke of Tuscany (later to become Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor) from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine into Freemasonry, which was at the time being used as an intelligence network by the British Whigs.

In 1733, Lord Chesterfield married Melusina von der Schulenberg, the Countess of Walsingham, who was the illegitimate daughter of the late King George I and his mistress, the Duchess of Kendal. After recuperating from his illness, Chesterfield resumed his seat in the House of Lords, of which he was now one of the acknowledged Leaders. He supported the ministry and leadership of Robert Walpole, the de facto Prime Minister, but withheld the blind fealty that Walpole preferred of his followers. Lord Chesterfield strongly opposed The Excise Bill, the Whig party leader's favourite measure, in the House of Lords while his brothers argued against it in the House of Commons. Even though Walpole eventually succumbed to the political fury and abandoned the measure, Chesterfield was summarily dismissed from his stewardship. For the next two years, he led the opposition in the Upper House to effect Walpole's downfall. During this time, he resided in Grosvenor Square and got involved in the creation of a new London charity called the Foundling Hospital, for which he was a founding governor.

In 1741, he signed the protest for Walpole's dismissal and went abroad on account of his health; after visiting Voltaire in Brussels, Lord Chesterfield went to Paris where he associated with Writers and men of letters, including Crebillon the Younger, Fontenelle and Montesquieu. In 1742, Walpole's fall from political power was complete, but although he and his administration had been overthrown in no small part due to Chesterfield's efforts, the new ministry did not count Chesterfield either in its ranks or among its supporters. He remained in opposition, distinguishing himself by the courtly bitterness of his attacks on King George II, who learned to hate him violently.

In 1743, Chesterfield began writing under the name of "Jeffrey Broadbottom" for pamphlets and a new journal, Old England; or, the Constitutional Journal that appeared with quick circulation (broad bottom being a term for a government with cross-party appeal). A number of pamphlets, in some of which Chesterfield had the help of Edmund Waller, followed. His energetic campaign against George II and his government won the gratitude of the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough, who left him £20,000 as a mark of her appreciation. In 1744, the king was compelled to abandon Lord Carteret, successor to Robert Walpole, and the coalition for a "Broad Bottom" party, led by Chesterfield and Pitt, came into office in coalition with the Pelhams.

In 1746, however, he had to exchange the Lord-Lieutenancy for Secretary of State. Chesterfield had hoped to retain a hold over the king through the influence of Lady Yarmouth, the mistress of George II, but John Montagu (4th Earl of Sandwich) and Thomas Pelham-Holles (1st Duke of Newcastle) combined forces against him, and in 1748, he resigned the seals and returned to his books and playing cards with the admirable composure that was one of his most striking characteristics. Despite his denials, Lord Chesterfield is speculated to have at least helped write Apology for a late Resignation, in a Letter from an English Gentleman to his Friend at The Hague, which ran for four editions in 1748.

While continuing to attend and participate in the Upper House proceedings, Lord Chesterfield turned down the dukedom offered him by King George II, whose wrath had melted in the face of Chesterfield's diplomacy and rhetoric. In 1751, seconded by George Parker, 2nd Earl of Macclesfield, President of the Royal Society, and the Mathematician James Bradley, Chesterfield greatly distinguished himself in the debates on establishing a definitive calendar for Britain and the Commonwealth. With the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, he successfully established the Gregorian calendar and a calendar year that begins on the 1st of January for the British realm; informally, the calendar act also is known as "Chesterfield′s Act". Around this time he started gradually withdrawing from both politics and society, due to his growing deafness.

Left without a legitimate heir to his lands and property -he and his wife, Melusina von der Schulenburg had no children together- Lord Chesterfield acted to protect his hereditary interests by adopting his distant cousin and Godson, Philip Stanhope (1755–1815), as his heir and successor to the title Earl of Chesterfield.

In the 1760s, Chesterfield offered a cogent critique of the Stamp Act 1765 passed by Grenville's parliament. In a letter to his friend, the Duke of Newcastle, Chesterfield noted the absurdity of the Stamp Act because it could not be properly enforced, but, if effective, the Act would generate a revenue no greater than eighty-thousand pounds sterling per year, whilst the annual cost of reduced trade from the American colonies would be about one million pounds sterling.

In 1768 Chesterfield's beloved yet illegitimate son, Philip Stanhope, died in France of dropsy, leaving behind his widow, Eugenia Stanhope and their two illegitimate sons, Charles and Philip. Despite his short life, the privileged education provided by his father, Lord Chesterfield, allowed Philip Stanhope an honourable career in the diplomatic Service of Britain, despite being handicapped as a nobleman's illegitimate son. The grieving Chesterfield was disappointed to learn that Philip's long and mostly secret marriage had been to Eugenia, a woman of humble social class, since this was a topic he'd covered at length in the Letters to his Son; however, Lord Chesterfield bequeathed an annuity of ₤100 to each of his grandsons, Charles Stanhope (1761–1845) and Philip Stanhope (1763–1801), and a further £10,000 for them both, yet left no pension for his widowed daughter-in-law, Eugenia. It was this lack of funds that led to Eugenia selling the Letters to his Son to a publisher.

The 4th Earl of Chesterfield (Philip Dormer Stanhope) died on 24 March 1773, at Chesterfield House, Westminster, his London townhouse (built about 1749). His Godson and adopted heir then became Lord Philip Stanhorpe, 5th Earl of Chesterfield.

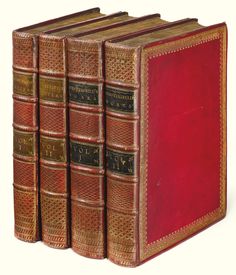

Despite having been an accomplished Essayist and epigrammatist in his time, Lord Chesterfield's literary reputation today derives almost entirely from Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774) and Letters to His Godson (1890), books of private correspondence and paternal and avuncular advice, which he never intended for publication.

Decades after his death, Lord Chesterfield appears as a character in the novel The Virginians (1857), by william Makepeace Thackeray, and is mentioned in the novel Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty (1841), by Charles Dickens, wherein the foppish Sir John Chester says that Lord Chesterfield is the finest English writer:

As a handbook for worldly success in the 18th century, the Letters to His Son give perceptive and nuanced advice for how a gentleman should interpret the social codes that are manners, for example:

Eugenia Stanhope, the impoverished widow of Chesterfield’s illegitimate son, Philip Stanhope was the first to publish the book Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774), which comprises a thirty-year correspondence in more than four hundred letters. Begun in the 1737 and continued until the death of his son in 1768, Chesterfield wrote mostly instructive communications about geography, history, and classical literature, -with later letters focusing on politics and diplomacy- and the letters themselves were written in French, English, and Latin, in order to refine his son's grasp of the languages.