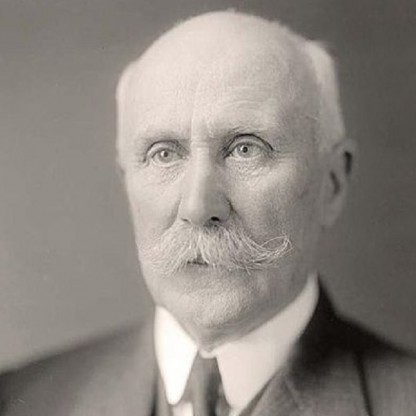

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Marshal of France |

| Birth Day | April 24, 1856 |

| Birth Place | Cauchy-à-la-Tour, French |

| Age | 163 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 23 July 1951(1951-07-23) (aged 95)\nFort de Pierre-Levée citadel prison, Île d'Yeu, Vendée, France |

| Birth Sign | Taurus |

| Prime Minister | Gaston Doumergue |

| Preceded by | Joseph Paul-Boncour |

| Succeeded by | Louis Maurin |

| President | Albert Lebrun |

| Deputy | Camille Chautemps Pierre Laval Pierre-Étienne Flandin François Darlan |

| Spouse(s) | Eugénie Hardon Pétain (m. 1920) |

| Awards | Marshal of France Legion of Honor Military Medal (Spain) |

| Allegiance | French Third Republic Vichy France |

| Service/branch | French Army |

| Years of service | 1876–1944 |

| Rank | Général de division |

| Battles/wars | World War I Battle of Verdun Rif Wars |

Net worth: $18 Million (2024)

Philippe Pétain, also known as Marshal of France in French, has an estimated net worth of $18 million in 2024. Pétain, who served as a military officer and statesman during the early 20th century, had a successful and influential career. His rise to prominence came during World War I when he led the French army to several victories, earning him the title of Marshal. However, his legacy took a dark turn during World War II when he collaborated with Nazi Germany as head of the Vichy France regime. Despite the controversies surrounding his later years, Pétain's esteemed military career undoubtedly contributed to his amassed wealth.

Biography/Timeline

Pétain was born in Cauchy-à-la-Tour (in the Pas-de-Calais département in Northern France) in 1856. His father, Omer-Venant, was a farmer. His great-uncle, a Catholic priest, Father Abbe Lefebvre, had served in Napoleon's Grande Armée and told the young Pétain tales of war and adventure of his campaigns from the peninsulas of Italy to the Alps in Switzerland. Highly impressed by the tales told by his uncle, his destiny was from then on determined.

Pétain joined the French Army in 1876 and attended the St Cyr Military Academy in 1887 and the École Supérieure de Guerre (army war college) in Paris. Between 1878 and 1899, he served in various garrisons with different battalions of the Chasseurs à pied, the elite light infantry of the French Army. Thereafter, he alternated between staff and regimental assignments.

Pétain's career progressed slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower kills". His views were later proved to be correct during the First World War. He was promoted to captain in 1890 and major (Chef de Bataillon) in 1900. Unlike many French officers, he served mainly in mainland France, never French Indochina or any of the African colonies, although he participated in the Rif campaign in Morocco. As colonel, he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras from 1911; the young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle, who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel, Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command". In the spring of 1914, he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of colonel). However, aged 58 and having been told he would never become a general, Pétain had bought a villa for retirement.

Pétain led his brigade at the Battle of Guise (29 August 1914). At the end of August 1914 he was quickly promoted to brigadier-general and given command of the 6th Division in time for the First Battle of the Marne; little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again and became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the spring 1915 Artois Offensive, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army, which he led in the Champagne Offensive that autumn. He acquired a reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western Front.

Pétain commanded the Second Army at the start of the Battle of Verdun in February 1916. During the battle he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Centre, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two weeks on the front lines. His decision to organise truck transport over the "Voie Sacrée" to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect, he applied the basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the École de Guerre (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue!" or "firepower kills!"—in this case meaning French field artillery, which fired over 15 million shells on the Germans during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did say "On les aura!" (an echoing of Joan of Arc, roughly: "We'll get them!"), the other famous quotation often attributed to him – "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass"!) – was actually uttered by Robert Nivelle who succeeded him in command of the Second Army at Verdun in May 1916. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over Pétain to replace Joseph Joffre as French Commander-in-Chief.

Pétain conducted some successful but limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn. Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which did not happen until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: "I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans."

On 10 June, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand, the Commander-in-Chief, now declared that "the fighting had become meaningless". He, Baudouin, and several members of the government were already set on an armistice. On 11 June, Churchill flew to the Château du Muguet, at Briare, near Orléans, where he put forward first his idea of a Breton redoubt, to which Weygand replied that it was just a "fantasy". Churchill then said the French should consider "guerrilla warfare". Pétain then replied that it would mean the destruction of the country. Churchill then said the French should defend Paris and reminded Petain of how he had come to the aid of the British with forty divisions in March 1918, and repeating Clemenceau's words "I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris". To this, Churchill subsequently reported, Pétain replied quietly and with dignity that he had in those days a strategic reserve of sixty divisions; now, there were none, and the British ought to be providing divisions to aid France. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event. At the conference Pétain met de Gaulle for the first time in two years. Pétain noted his recent promotion to general, adding that he did not congratulate him, as ranks were of no use in defeat. When de Gaulle protested that Pétain himself had been promoted to brigadier-general and division commander at the Battle of the Marne in 1914, he replied that there was “no comparison” with the present situation. De Gaulle later conceded that Pétain was right about that much at least.

Mount Pétain, nearby Pétain Creek, and Pétain Falls, forming the Pétain Basin on the Continental Divide in the Canadian Rockies, were named after him in 1919; summits with the names of other French generals are nearby: Foch, Cordonnier, Mangin, Castelnau and Joffre. Hengshan Road, in Shanghai, was "Avenue Pétain" between 1922 and 1943.

Shortly after the war, Pétain had placed before the government plans for a large tank and air force but "at the meeting of the Conseil supérieur de la Défense Nationale of 12 March 1920 the Finance Minister, François-Marsal, announced that although Pétain's proposals were excellent they were unaffordable". In addition, François-Marsal announced reductions – in the army from fifty-five divisions to thirty, in the air force, and did not mention tanks. It was left to the Marshals, Pétain, Joffre, and Foch, to pick up the pieces of their strategies. The General Staff, now under General Edmond Buat, began to think seriously about a line of forts along the frontier with Germany, and their report was tabled on 22 May 1922. The three Marshals supported this. The cuts in military expenditure meant that taking the offensive was now impossible and a defensive strategy was all they could have.

Some argue that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, should bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry preparation before World War II. But Pétain was only one of many military and other men on a very large committee responsible for national defence, and interwar governments frequently cut military budgets. In addition, with the restrictions imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty there seemed no urgency for vast expenditure until the advent of Hitler. It is argued that while Pétain supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanised cavalry (such as the SOMUA S35) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis). Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured, with the sole exception of a light machine-rifle, the Mle 1924. The French heavy machine gun was still the Hotchkiss M1914, a capable weapon but decidedly obsolete compared to the new automatic weapons of German infantry. A modern infantry rifle was adopted in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles had been issued to the troops by 1940. A well-tested French semiautomatic rifle, the MAS 1938–39, was ready for adoption but it never reached the production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49. As to French artillery it had, basically, not been modernised since 1918. The result of all these failings is that the French Army had to face the invading enemy in 1940, with the dated weaponry of 1918. Pétain had been made, briefly, Minister of War in 1934. Yet his short period of total responsibility could not reverse 15 years of inactivity and constant cutbacks. The War Ministry was hamstrung between the wars and proved unequal to the tasks before them. French aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber aeroplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine, Morane-Saulnier and Marcel Bloch), each with its own Models. On the naval front, France had purposely overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on four new conventional battleships, not unlike the German Navy.

On 5 December 1925, after the Locarno Treaty, the Conseil demanded immediate action on a line of fortifications along the eastern frontier to counter the already proposed decline in manpower. A new commission for this purpose was established, under Joseph Joffre, and called for reports. In July 1927 Pétain himself went to reconnoitre the whole area. He returned with a revised plan and the commission then proposed two fortified regions. The Maginot Line, as it came to be called, (named after André Maginot the former Minister of War) thereafter occupied a good deal of Pétain's attention during 1928, when he also travelled extensively, visiting military installations up and down the country. Pétain had based his strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

On October 26, 1931 Pétain was honored with a ticker-tape parade down Manhattan's Canyon of Heroes. Consideration has been given to removing the sidewalk ribbon denoting the parade for Pétain given his role with the Nazis in World War II.

Political unease was sweeping the country, and on 6 February 1934 the Paris police fired on a group of far-right rioters outside the Chamber of Deputies, killing 14 and wounding a further 236. President Lebrun invited 71-year-old Doumergue to come out of retirement and form a new "government of national unity". Pétain was invited, on 8 February, to join the new French cabinet as Minister of War, which he only reluctantly accepted after many representations. His important success that year was in getting Daladier's previous proposal to reduce the number of officers repealed. He improved the recruitment programme for specialists, and lengthened the training period by reducing leave entitlements. However Weygand reported to the Senate Army Commission that year that the French Army could still not resist a German attack. Marshals Louis Franchet d'Espèrey and Hubert Lyautey (the latter suddenly died in July) added their names to the report. After the autumn maneuvers, which Pétain had reinstated, a report was presented to Pétain that officers had been poorly instructed, had little basic knowledge, and no confidence. He was told, in addition, by Maurice Gamelin, that if the plebiscite in the Territory of the Saar Basin went for Germany it would be a serious military error for the French Army to intervene. Pétain responded by again petitioning the government for further funds for the army. During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term of compulsory military Service for conscripts from two to three years, to no avail. Pétain accompanied President Lebrun to Belgrade for the funeral of King Alexander, who had been assassinated on 6 October 1934 in Marseille by Vlado Chernozemski, a Macedonian nationalist of Bulgarian origin. Here he met Hermann Göring and the two men reminisced about their experiences in the Great War. "When Goering returned to Germany he spoke admiringly of Pétain, describing him as a 'man of honour'".

He remained on the Conseil superieur. Weygand had been at the British Army 1934 manoeuvres at Tidworth Camp in June and was appalled by what he had seen. Addressing the Conseil on the 23rd, Pétain claimed that it would be fruitless to look for assistance to Britain in the event of a German attack. On 1 March 1935 Pétain's famous article appeared in the Revue des deux mondes where he reviewed the history of the army since 1927–28. He criticised the reservist system in France, and her lack of adequate air power and armour. This article appeared just five days before Adolf Hitler's announcement of Germany's new air force and a week before the announcement that Germany was increasing its army to 36 divisions. On 26 April 1936 the general election results showed 5.5 million votes for the Popular Front parties against 4.5 million for the Right on an 84% turnout. On 3 May Pétain was interviewed in Le Journal where he launched an attack on the Franco-Soviet Pact, on Communism in general (France had the largest communist party in Western Europe), and on those who allowed Communists intellectual responsibility. He said that France had lost faith in her destiny. Pétain was now in his 80th year.

In 1938 Pétain encouraged and assisted the Writer André Maurois in gaining election to the Académie française – an election which was highly contested, in part due to Maurois' Jewish origin. Maurois made a point of acknowledging with thanks his debt to Pétain in his 1941 autobiography, Call no man happy – though by the time of writing their paths had sharply diverged, Pétain having become Head of State of Vichy France while Maurois went into exile and sided with the Free French.

He and his government collaborated with Germany and even produced a legion of volunteers to fight in Russia. Pétain's government was nevertheless internationally recognised, notably by the U.S., at least until the German occupation of the rest of France. Neither Pétain nor his successive deputies, Laval, Pierre-Étienne Flandin, or Admiral François Darlan, gave significant resistance to requests by the Germans to indirectly aid the Axis Powers. However, when Hitler met Pétain at Montoire in October 1940 to discuss the French government's role in the new European Order, the Marshal "listened to Hitler in silence. Not once did he offer a sympathetic word for Germany." Still, the handshake he offered to Hitler caused much uproar in London, and probably influenced Britain's decision to lend the Free French naval support for their operations at Gabon. Furthermore, France even remained formally at war with Germany, albeit opposed to the Free French. Following the British attacks of July and September 1940 (Mers el Kébir, Dakar), the French government became increasingly fearful of the British and took the initiative to collaborate with the occupiers. Pétain accepted the government's creation of a collaborationist armed militia (the Milice) under the command of Joseph Darnand, who, along with German forces, led a campaign of repression against the French resistance ("Maquis").

On 11 November 1942, German forces invaded the unoccupied zone of Southern France in response to the Allies' Operation Torch landings in North Africa and Admiral François Darlan's agreement to support the Allies. Although the French government nominally remained in existence, civilian administration of almost all France being under it, Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead, as the Germans had negated the pretence of an "independent" government at Vichy. Pétain however remained popular and engaged in a series of visits around France as late as 1944, when he arrived in Paris on 28 April in what Nazi propaganda newsreels described as a "historic" moment for the city. Vast crowds cheered him in front of the Hôtel de Ville and in the streets.

Following the liberation of France, on 7 September 1944 Pétain and other members of the French cabinet at Vichy were relocated by the Germans to the Sigmaringen enclave in Germany, where they became a government-in-exile until April 1945. Pétain, however, having been forced to leave France, refused to participate in this government and Fernand de Brinon now headed the 'government commission.' In a note dated 29 October 1944, Pétain forbade de Brinon to use the Marshal's name in any connection with this new government, and on 5 April 1945, Pétain wrote a note to Hitler expressing his wish to return to France. No reply ever came. However, on his birthday almost three weeks later, he was taken to the Swiss border. Two days later he crossed the French frontier.

Fearing riots at the announcement of the sentence, De Gaulle ordered that Pétain be immediately transported on the former's private aircraft to Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees, where he remained from 15 August to 16 November 1945. The government later transferred him to the Fort de Pierre-Levée citadel on the Île d'Yeu, a small island off the French Atlantic coast.

Over the following years Pétain's lawyers and many foreign governments and dignitaries, including Queen Mary and the Duke of Windsor, appealed to successive French governments for Pétain's release, but given the unstable state of Fourth Republic politics no government was willing to risk unpopularity by releasing him. As early as June 1946 US President Harry Truman interceded in vain for his release, even offering to provide political asylum in the U.S. A similar offer was later made by the Spanish dictator General Franco.

Although Pétain had still been in good health for his age at the time of his imprisonment, by late 1947 his memory lapses were worsening and he was beginning to suffer from incontinence, sometimes soiling himself in front of visitors and sometimes no longer recognising his wife. By January 1949 his lucid intervals were becoming fewer and fewer. On 3 March 1949, a meeting of the Council of Ministers (many of them "self-proclaimed heroes of the Resistance" in the words of biographer Charles Williams) had a fierce argument about a medical report recommending that he be moved to Val-de-Grâce (a military hospital in Paris), a measure to which Prime Minister Henri Queuille had previously been sympathetic. By May, Pétain required constant nursing care, and he was often suffering from hallucinations, e.g. that he was commanding armies in battle, or that naked women were dancing around his room. By the end of 1949, Pétain was completely senile, with only occasional moments of lucidity. He was also beginning to suffer from heart problems and was no longer able to walk without assistance. Plans were made for his death and funeral.

On 8 June 1951 President Auriol, informed that Pétain had little longer to live, commuted his sentence to confinement in hospital (the news was kept secret until after the elections on 17 June), but by then Pétain was too ill to be moved. He died on the Île d'Yeu on 23 July 1951, at the age of 95, and is buried in a Marine cemetery (Cimetière communal de Port-Joinville) near the prison. Calls are sometimes made to re-inter his remains in the grave prepared for him in Verdun.

In February 1973, Pétain's coffin was stolen from the Île d'Yeu cemetery by extremists who demanded that President Georges Pompidou consent to his interment in the Douaumont cemetery among the war dead. Authorities retrieved the coffin a few days later, and Pétain was ceremoniously reburied with a Presidential wreath on his coffin, but on the Île d'Yeu as before.

The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, meeting together as a "Congrès", held an emergency meeting on 10 July to ratify the armistice. At the same time, the draft constitutional proposals were tabled. The Presidents of both Chambers spoke and declared that constitutional reform was necessary. The Congress voted 569–80 (with 18 abstentions) to grant the Cabinet the authority to draw up a new constitution, effectively "voting the Third Republic out of existence". Nearly all French historians, as well as all postwar French governments, consider this vote to be illegal; not only were several deputies and senators not present, but the constitution explicitly stated that the republican form of government could not be changed. On the next day, Pétain formally assumed near-absolute powers as "Head of State."

Pétain was reactionary by temperament and education, and quickly began blaming the Third Republic and its endemic corruption for the French defeat. His regime soon took on clear authoritarian—and in some cases, fascist—characteristics. The republican motto of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" was replaced with "Travail, famille, patrie" ("Work, family, fatherland"). He issued new constitutional acts which abolished the presidency, indefinitely adjourned parliament, and also gave him full power to appoint and fire ministers and civil Service members, pass laws through the Council of Ministers and designate a successor (he chose Laval). Though Pétain publicly stated that he had no Desire to become "a Caesar," by January 1941 Pétain held virtually all governing power in France; nearly all legislative, executive, and judicial powers were either de jure or de facto in his hands. One of his advisors commented that he had more power than any French leader since Louis XIV. Fascistic and revolutionary conservative factions within the new government used the opportunity to launch an ambitious program known as the "National Revolution", which rejected much of the former Third Republic's secular and liberal traditions in favour of an authoritarian, paternalist, Catholic society. Pétain, amongst others, took exception to the use of the inflammatory term "revolution" to describe an essentially conservative movement, but otherwise participated in the transformation of French society from "Republic" to "State." He added that the new France would be "a social hierarchy... rejecting the false idea of the natural equality of men."

"The enthusiasm of the country for the Maréchal was tremendous. He was welcomed by people as diverse as Claudel, Gide, and Mauriac, and also by the vast mass of untutored Frenchmen who saw him as their saviour." General de Gaulle, no longer in the Cabinet, had arrived in London on the 17th and made a call for resistance from there, on the 18th, with no legal authority whatsoever from his government, a call that was heeded by comparatively few.

Cabinet and Parliament still argued between themselves on the question of whether or not to retreat to North Africa. On 18 June, Édouard Herriot (who would later be a prosecution witness at Pétain's trial) and Jeanneney, the Presidents of the two Chambers of Parliament, as well as Lebrun said they wanted to go. Pétain said he was not departing. On the 20th, a delegation from the two chambers came to Pétain to protest at the proposed departure of President Lebrun. The next day, they went to Lebrun himself. In the event, only 26 deputies and 1 senator headed for Africa, amongst them those with Jewish backgrounds, Georges Mandel, Pierre Mendès France, and the former Popular Front Education Minister, Jean Zay. Pétain broadcast again to the French people on that day.

His sometime protégé Charles de Gaulle later wrote that Pétain’s life was “successively banal, then glorious, then deplorable, but never mediocre”.