Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Geographer, Explorer |

| Birth Place | Marseille, France, Greek |

| Died On | Approximately 285 BC |

| Citizenship | Massaliote |

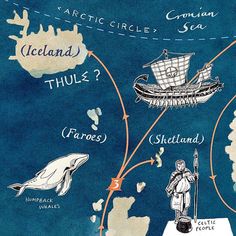

| Known for | Earliest voyage to Britain, the Baltic, and the Arctic Circle for which there is a record, author of Periplus. |

| Fields | Geography, exploration, navigation |

| Influenced | Subsequent classical geographers and explorers |

Net worth

Pytheas, a renowned Geographer and Explorer in ancient Greece, is believed to have amassed a considerable fortune. As we delve into history, his net worth is estimated to range between $100,000 and $1 million by the year 2024. Known for his daring voyages and groundbreaking discoveries, Pytheas' expeditions to far-flung lands brought him fame and wealth. His ability to accurately navigate uncharted territories and map vast regions allowed him to establish lucrative trade routes, ensuring a steady influx of riches. This estimation of his net worth serves as a testament to Pytheas' extraordinary achievements and the immense value his contributions brought to the ancient world of exploration.

Famous Quotes:

... the Barbarians showed us the place where the sun goes to rest. For it was the case that in these parts the nights were very short, in some places two, in others three hours long, so that the sun rose again a short time after it had set.

Biography/Timeline

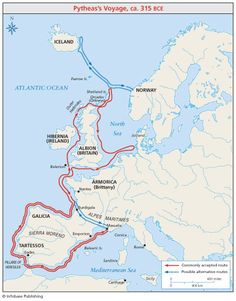

An alternate theory holds that by the 4th century BC, the western Greeks, especially the Massaliotes, were on amicable terms with Carthage. In 348 BC, Carthage and Rome came to terms over the Sicilian Wars with a treaty defining their mutual interests. Rome could use Sicilian markets, Carthage could buy and sell goods at Rome, and slaves taken by Carthage from allies of Rome were to be set free. Rome was to stay out of the western Mediterranean, but these terms did not apply to Massalia, which had its own treaty. During the second half of the 4th century BC, the time of Pytheas' voyage, Massaliotes were presumably free to operate as they pleased; there is, at least, no evidence of conflict with Carthage in any of the sources that touch on the voyage.

Pliny reports that "Pytheas of Massalia informs us, that in Britain the tide rises 80 cubits." The passage does not give enough information to determine which cubit Pliny meant; however, any cubit gives the same general result. If he was reading an early source, the cubit may have been the Cyrenaic cubit, an early Greek cubit, of 463.1 mm, in which case the distance was 37 metres (121 ft). This number far exceeds any modern known tides. The National Oceanography Centre, which records tides at tidal gauges placed in about 55 ports of the UK Tide Gauge Network on an ongoing basis, records the highest mean tidal change between 1987 and 2007 at Avonmouth in the Severn Estuary of 6.955 m (22.82 ft). The highest predicted spring tide between 2008 and 2026 at that location will be 14.64 m (48.0 ft) on 29 September 2015. Even allowing for geologic and climate change, Pytheas' 80 cubits far exceeds any known tides around Britain. One well-circulated but unevidenced answer to the paradox is that Pytheas is referring to a storm surge.

Pliny says that Timaeus (born about 350 BC) believed Pytheas' story of the discovery of amber. Strabo says that Dicaearchus (died about 285 BC) did not trust the stories of Pytheas. That is all the information that survives concerning the date of Pytheas' voyage. Presuming that Timaeus would not have written until after he was 20 years old in about 330 BC and Dicaearchus would have needed time to write his most mature work, after 300 BC, there is no reason not to accept Henry Fanshawe Tozer's window of 330–300 BC for the voyage. Some would give Timaeus an extra 5 years, bringing the voyage down to 325 BC at earliest. There is no further evidence.

The start of Pytheas's voyage is unknown. The Carthaginians had closed the Strait of Gibraltar to all ships from other nations. Some historians, mainly of the late 19th century and before, therefore speculated (on no evidence) that he must have traveled overland to the mouth of the Loire or the Garonne. Others believed that, to avoid the Carthaginian blockade, he may have stuck close to land and sailed only at night, or taken advantage of a temporary lapse in the blockade.