Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | King |

| Birth Place | Handan, Chinese |

| Died On | 10 September 210 BC (aged 49) |

| Reign | 220 BC – 10 September 210 BC |

| Predecessor | King Zhuangxiang |

| Successor | Qin Er Shi |

| Issue | Crown Prince Fusu Qin Er Shi Prince Gao Prince Jianglü |

| Full name | Full name 姓 Ancestral name: Ying (嬴) 氏 Clan name: Zhao (趙) 名 Given name: Zheng (政) 姓 Ancestral name: Ying (嬴) 氏 Clan name: Zhao (趙) 名 Given name: Zheng (政) |

| House | Qin |

| Father | King Zhuangxiang |

| Mother | Queen Dowager Zhao |

| Chinese | 始皇帝 |

| Literal meaning | "First Emperor" |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinWade–GilesIPAYue: CantoneseYale RomanizationIPAJyutpingSouthern MinHokkien POJMiddle ChineseMiddle ChineseOld ChineseBaxter (1992)Baxter–Sagart (2014) | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Qín shǐ huáng Wade–Giles Ch‘in shih huang IPA [tɕʰǐn ʂɨ̀ xwǎŋ] ( listen) Yue: Cantonese Yale Romanization Chèuhn chí wòhng IPA [tsʰɵ̏n tsʰǐː wɔ̏ːŋ] Jyutping Ceon ci wong Southern Min Hokkien POJ Tsîn sí hông Middle Chinese Middle Chinese Dzin si hwang Old Chinese Baxter (1992) *dzin hlɨjʔ waŋ Baxter–Sagart (2014) *dzin l̻əʔ ɢʷˤaŋ Qín shǐ huángCh‘in shih huang[tɕʰǐn ʂɨ̀ xwǎŋ] ( listen)Chèuhn chí wòhng[tsʰɵ̏n tsʰǐː wɔ̏ːŋ]Ceon ci wongTsîn sí hôngDzin si hwang*dzin hlɨjʔ waŋ*dzin l̻əʔ ɢʷˤaŋ |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shǐ Huángdì |

| Wade–Giles | Shih Huang-ti |

| IPA | [tsʰɵ̏n tsʰǐː wɔ̏ːŋ] |

| Yale Romanization | Chèuhn chí wòhng |

| Jyutping | Ceon ci wong |

| Hokkien POJ | Tsîn sí hông |

| Middle Chinese | Dzin si hwang |

| Baxter (1992) | *dzin hlɨjʔ waŋ |

| Baxter–Sagart (2014) | *l̻əʔ ɢʷˤaŋ tˤek-s |

| TranscriptionsStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinWade–GilesOld ChineseBaxter–Sagart (2014) | Transcriptions Standard Mandarin Hanyu Pinyin Shǐ Huángdì Wade–Giles Shih Huang-ti Old Chinese Baxter–Sagart (2014) *l̻əʔ ɢʷˤaŋ tˤek-s Shǐ HuángdìShih Huang-ti*l̻əʔ ɢʷˤaŋ tˤek-s |

Net worth

Qin Shi Huang, also known as the King in Chinese, is estimated to have a net worth ranging between $100K to $1M in the year 2024. Qin Shi Huang, who reigned as the first emperor of China after unifying the country, amassed a considerable wealth during his reign. His net worth is believed to be a result of his vast empire, which included abundant natural resources, extensive land holdings, and a prosperous economy. Qin Shi Huang's wealth is a testament to his successful rule and the economic prosperity of ancient China.

Famous Quotes:

Qin, from a tiny base, had become a great power, ruling the land and receiving homage from all quarters for a hundred odd years. Yet after they unified the land and secured themselves within the pass, a single common rustic could nevertheless challenge this empire... Why? Because the ruler lacked humaneness and rightness; because preserving power differs fundamentally from seizing power.

Biography/Timeline

However, the Records of the Grand Historian also claimed that the first Emperor was not the actual son of Prince Yiren but that of Lü Buwei. According to this account, when Lü Buwei introduced the dancing girl to the Prince, she was Lü Buwei's concubine and had already become pregnant by him, and the baby was born after an unusually long period of pregnancy. According to translations of the Annals of Lü Buwei, Zhao Ji gave birth to the Future Emperor in the city of Handan in 259 BC, the first month of the 48th year of King Zhaoxiang of Qin.

Another Historian, Ma Feibai (馬非百), published in 1941 a full-length revisionist biography of the First Emperor entitled Qín Shǐ Huángdì Zhuàn (秦始皇帝傳), calling him "one of the great heroes of Chinese history". Ma compared him with the contemporary leader Chiang Kai-shek and saw many parallels in the careers and policies of the two men, both of whom he admired. Chiang's Northern Expedition of the late 1920s, which directly preceded the new Nationalist government at Nanjing was compared to the unification brought about by Qin Shi Huang.

With the coming of the Communist Revolution and the establishment of a new, revolutionary regime in 1949, another re-evaluation of the First Emperor emerged as a Marxist critique. This new interpretation of Qin Shi Huang was generally a combination of traditional and modern views, but essentially critical. This is exemplified in the Complete History of China, which was compiled in September 1955 as an official survey of Chinese history. The work described the First Emperor's major steps toward unification and standardisation as corresponding to the interests of the ruling group and the merchant class, not of the nation or the people, and the subsequent fall of his dynasty as a manifestation of the class struggle. The perennial debate about the fall of the Qin Dynasty was also explained in Marxist terms, the peasant rebellions being a revolt against oppression – a revolt which undermined the dynasty, but which was bound to fail because of a compromise with "landlord class elements".

Since 1972, however, a radically different official view of Qin Shi Huang in accordance with Maoist thought has been given prominence throughout China. Hong Shidi's biography Qin Shi Huang initiated the re-evaluation. The work was published by the state press as a mass popular history, and it sold 1.85 million copies within two years. In the new era, Qin Shi Huang was seen as a far-sighted ruler who destroyed the forces of division and established the first unified, centralized state in Chinese history by rejecting the past. Personal attributes, such as his quest for immortality, so emphasized in traditional historiography, were scarcely mentioned. The new evaluations described approvingly how, in his time (an era of great political and social change), he had no compunctions against using violent methods to crush counter-revolutionaries, such as the "industrial and commercial slave owner" chancellor Lü Buwei. However, he was criticized for not being as thorough as he should have been, and as a result, after his death, hidden subversives under the leadership of the chief eunuch Zhao Gao were able to seize power and use it to restore the old feudal order.

To round out this re-evaluation, Luo Siding put forward a new interpretation of the precipitous collapse of the Qin Dynasty in an article entitled "On the Class Struggle During the Period Between Qin and Han" in a 1974 issue of Red Flag, to replace the old explanation. The new theory claimed that the cause of the fall of Qin lay in the lack of thoroughness of Qin Shi Huang's "dictatorship over the reactionaries, even to the extent of permitting them to worm their way into organs of political authority and usurp important posts."

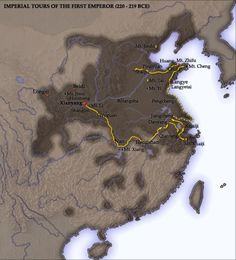

Following the surrender of Qi in 221 BC, King Zheng had reunited all of the lands of the former Kingdom of Zhou. Rather than maintain his rank as king, however, he created a new title of huángdì (emperor) for himself. This new title combined two titles—huáng of the mythical Three Sovereigns (三皇, Sān Huáng) and the dì of the legendary Five Emperors (五帝, Wŭ Dì) of Chinese prehistory. The title was intended to appropriate some of the prestige of the Yellow Emperor, whose cult was popular in the later Warring States period and who was considered to be a founder of the Chinese people. King Zheng chose the new regnal name of First Emperor (Shǐ Huángdì, formerly transcribed as Shih Huang-ti) on the understanding that his successors would be successively titled the "Second Emperor", "Third Emperor", and so on through the generations. (In fact, the scheme lasted only as long as his immediate heir, the Second Emperor.) The new title carried religious overtones. For that reason, Sinologists—starting with Peter Boodberg or Edward Schafer—sometimes translate it as "thearch" and the First Emperor as the First Thearch.

The idea that the Emperor was an illegitimate child, widely believed throughout Chinese history, contributed to the generally negative view of the First Emperor. However, a number of modern scholars have doubted this account of his birth. Sinologist Derk Bodde wrote: "There is good reason for believing that the sentence describing this unusual pregnancy is an interpolation added to the Shih-chi by an unknown person in order to slander the First Emperor and indicate his political as well as natal illegitimacy". John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, in their translation of Lü Buwei's Spring and Autumn Annals, call the story "patently false, meant both to libel Lü and to cast aspersions on the First Emperor". Claiming Lü Buwei – a merchant – as the First Emperor's biological father was meant to be especially disparaging, since later Confucian society regarded merchants as the lowest of all social classes.

Modern Chinese sources often give the personal name of Qin Shi Huang as Ying Zheng, with Ying (嬴) taken as the surname and Zheng (政) the given name. In ancient China however the naming convention differed, and Zhao (趙) may be used as the surname. Unlike modern Chinese names, the nobles of ancient China had two distinct surnames: the ancestral name (姓) comprised a larger group descended from a prominent ancestor, usually said to have lived during the time of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors of Chinese legend, and the clan name (氏) comprised a smaller group that showed a branch's current fief or recent title. (This is remarkably similar to the practice of contemporary Romans for naming men, such as M. Tullius Cicero and C. Julius Caesar.) The ancient practice was to list men's names separately—in Sima Qian's "Basic Annals of the First Emperor of Qin" introduces him as "given the name Zheng and the surname Zhao"—or to combine the clan surname with the personal name: Sima's account of Chu describes the sixteenth year of the reign of King Kaolie as "the time when Zhao Zheng was enthroned as King of Qin". However, since modern Chinese Surnames (despite usually descending from clan names) use the same character as the old ancestral names, it is much more Common in modern Chinese sources to see the emperor's personal name written as Ying Zheng, using the ancestral name of the Ying family.

In more modern times, historical assessment of the First Emperor different from traditional Chinese historiography began to emerge. The reassessment was spurred on by the weakness of China in the latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century. At that time some began to regard Confucian traditions as an impediment to China's entry into the modern world, opening the way for changing perspectives.