Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Former Chancellor of the Exchequer |

| Birth Day | December 09, 1902 |

| Birth Place | Attock, British |

| Age | 118 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 8 March 1982(1982-03-08) (aged 79)\nGreat Yeldham, Essex, England, UK |

| Birth Sign | Capricorn |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Oliver Stanley |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Gaitskell |

| Leader | Winston Churchill |

| Sec. of State | The Viscount Halifax Anthony Eden |

| Shadow Cabinet positions Shadow Foreign SecretaryLeaderShadowingPreceded bySucceeded byShadow Chancellor of the ExchequerLeaderShadowingPreceded bySucceeded by | Shadow Cabinet positions Shadow Foreign Secretary In office 16 October 1964 – 27 July 1965 Leader Alec Douglas-Home Shadowing Patrick Gordon Walker Michael Stewart Preceded by Patrick Gordon-Walker Succeeded by Reginald Maudling Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer In office 10 December 1950 – 28 October 1951 Leader Winston Churchill Shadowing Hugh Gaitskell Preceded by Oliver Stanley Succeeded by Hugh Gaitskell In office 16 October 1964 – 27 July 1965Alec Douglas-HomePatrick Gordon Walker Michael StewartPatrick Gordon-WalkerReginald MaudlingIn office 10 December 1950 – 28 October 1951Winston ChurchillHugh GaitskellOliver Stanley Hugh Gaitskell |

| Shadowing | Hugh Gaitskell |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Cambridge |

Net worth: $11 Million (2024)

Rab Butler, the notable British politician who served as the Former Chancellor of the Exchequer, is estimated to have a net worth of around $11 million as of 2024. Throughout his distinguished career, Butler held several significant positions in the British government, displaying his expertise in economic matters. As Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was responsible for managing the nation's finances and played a crucial role in shaping economic policies. His vast experience and impressive track record have likely contributed to his substantial net worth, reflecting both his successful political career and the financial advantages that come with such high-profile positions.

Famous Quotes:

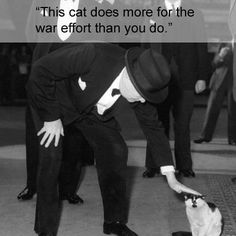

Rab said he thought that the good clean tradition of English politics, that of Pitt as opposed to Fox, had been sold to the greatest adventurer of modern political history. He had tried earnestly and long to persuade Halifax to accept the Premiership, but he had failed. He believed this sudden coup of Winston and his rabble was a serious disaster and an unnecessary one: the 'pass has been sold' by Mr. C., Lord Halifax and Oliver Stanley. They had weakly surrendered to a half-breed American [i.e. Churchill] whose main support was that of inefficient but talkative people of a similar type.

Biography/Timeline

During his fourth year at Cambridge, he concentrated on study, reading for Part II in History and International Law. He was able to use notes which his uncle Geoffrey had prepared for a planned book on International Law. In his International Law exam, he was dissatisfied with his essays, and at half time, he tore up his answers and wrote six fresh ones on six sheets of foolscap. In History, he took the Peel special subject, at one point knowing by name which way every Conservative MP voted in the split over the Irish Coercion Bill of 1846. He received one of the highest firsts in the university across all subjects, known at the time as a "I:I".

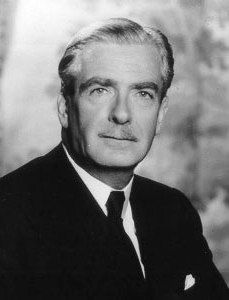

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, KG, CH, PC, DL (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), generally known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Politician. The Times obituary called him "the creator of the modern educational system, the key-figure in the revival of post-war Conservatism, arguably the most successful chancellor since the war and unquestionably a Home Secretary of reforming zeal." He was one of his party's Leaders in promoting the post-war consensus through which the major parties largely agreed on the main points of domestic policy until the 1970s, sometimes known as "Butskellism" from an elision of his name with that of his Labour counterpart Hugh Gaitskell.

As a child of Empire, from his mid-teens onwards, Butler was expected to look after his younger siblings, arranging for them to stay with relatives during school holidays and sending them Christmas presents that he pretended had been sent by their parents. His sister was the Writer Iris Mary Butler (born 1905), who became Iris Portal upon her marriage and her elder daughter is Jane Williams, Baroness Williams of Elvel, the mother of Justin Welby, the current Archbishop of Canterbury. Butler's younger brother Jock, a Home Office civil servant and Pilot Officer, was killed in a plane crash at the end of 1942.

In July 1909, at the age of six, his right arm was broken in three places in a riding accident. The injury was aggravated by a burn from a hot water bottle and an attempt to straighten the arm by hanging weights from it, leaving his hand not fully functional. His limp handshake and lack of military experience (and his stooping donnish manner at a time when many politicians were former officers) were political handicaps in later life.

Butler attended several preparatory schools but refused to attend Harrow, where many of his family had been educated. He failed to win a scholarship to Eton, and so he attended Marlborough College. He left Marlborough at the end of 1920, a week after his 18th birthday, and spent five months in France with a Protestant pastor in Abbeville. He returned briefly to England to sit the exams for Pembroke College, Cambridge, where in June 1921 he won an exhibition worth £20 per annum (around £1,000 at 2014 prices), then returned to France to be tutor to the son of Robert de Rothschild. His plan at this stage was to enter the Diplomatic Service.

Butler studied at Pembroke College, Cambridge, starting in October 1921, initially reading Medieval and Modern Languages. He soon became active in student politics, being elected to the Committee of the Cambridge Union Society by the end of his first year. At the end of his second year, he was elected Secretary for Michaelmas (autumn term) 1923 at his second attempt, by the narrow margin of 10 votes out of 500. At that time, Secretary was the only office normally contested, putting him on track to be Vice-President for Lent 1924 and President for Easter (summer term) 1924. At the end of his second year (June 1923), he achieved a First in French Part I and was awarded an £80 scholarship to supplement his £300 parental allowance (approximately £4,000 and £15,000 at 2014 prices).

Heath (Chief Whip) and John Morrison (Chairman of the 1922 Committee) advised that the Suez group of right-wing Conservative backbenchers would be reluctant to follow Rab. The Whips rang Boothby (pro-Macmillan) in Strasbourg to obtain his views, but there is no evidence that they were very assiduous in canvassing known pro-Butler MPs.

Butler suffered a nervous breakdown that summer and had to postpone his plans to study History to a fourth year, taking a less strenuous course in German in the meantime. He spent part of the summer of 1923 abroad learning German, and became unusually fluent in the language, impressing his hosts with his near-native syntax. He also came to feel that the Germans had been harshly treated in the recent Treaty of Versailles.

In the summer of 1924 Butler took part in the ESU USA Tour, a seven-week debating tour of Canada and the United States run by the English-Speaking Union. They debated two motions: democracy versus personal liberty and closer relations with the Soviet Union.

Butler married Sydney Elizabeth Courtauld on 20 April 1926. She was the daughter of Samuel Courtauld and heiress to part of the Courtauld textile fortune. His father-in-law awarded him a private income of £5,000 a year after tax for life, the equivalent of a Cabinet Minister's salary, and equivalent to almost £260,000 at 2014 prices.

Butler spent a brief period as a don at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge from 1925, and gave lectures on the politics of the French Third Republic. In summer 1926, he resigned his residential fellowship to go on a honeymoon tour of the world, becoming instead a supernumerary fellow. He renewed his contact with Leo Amery, whom he had met in July 1924 at a British Empire Students Conference, and who now put him in touch with contacts in Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Whilst in Vancouver in June 1927, he learned of a vacancy for the safe Conservative seat of Saffron Walden, and returned from Quebec by sea on 31 August 1927; Courtauld connections arranged for him to be selected unopposed as the Conservative candidate on 26 November 1927. Butler toured local villages showing films of his Empire tours.

Butler was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Saffron Walden in the 1929 general election, and held the seat until his retirement, in 1965. His father advised him that he lacked facility for executive decision-making and that he should aim for the Speakership. He also warned him, in 1926, not to acquire a reputation as a bore by specialising in Indian affairs in Parliament. He then advised him, in 1929, that he should either devote his life to India as he had done or aim to come out later as a provincial governor or even as Viceroy.

In 1930, he referred to the rebels against Stanley Baldwin's leadership, led by the Press Barons Lords Rothermere and Beaverbrook, as the "Forty Thieves". He wrote of "Brigadier-General this and Colonel that" amongst Conservative backbenchers and thought Beaverbrook "green and apeish". Butler supported Duff Cooper in the Westminster St George's by-election, 1931 in March 1931.

In August 1931, when the National Government was formed, Butler was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to the India Secretary, Samuel Hoare. The India Committee, one of whose leading Lights was Winston Churchill, had been formed to resist plans for greater Indian self-government after the Gandhi-Irwin Pact. Sydney had written to Butler's mother that she would "pray for snow and sleet" if Mahatma Gandhi visited London in his loincloth. As PPS, Butler was Hoare's eyes and ears at the Second Round Table Conference then in progress. He was soon impressed by Gandhi. He was sent to India on Lord Lothian's Franchise Committee, one of three committees set up as part of the Round Table Conference. He left in January 1932 and returned on 21 May. The Committee recommended an increase in the Indian electorate from 7 million to 36 million.

Butler returned to find himself now a joint PPS with Micky Knatchbull, MP for Ashford in Kent. Butler soon reestablished himself as Hoare's main adviser and persuaded him to attend the Conservative Conference at Blackpool that October, where Churchill was planning to move a motion critical of the government's Indian policy. He was given his first ministerial job as Under-Secretary of State for India (29 September 1932) when Lord Lothian resigned along with the rest of Herbert Samuel's Official Liberals over the National Government's abandonment of free trade. At 29, he was the youngest member of the government.

At the end of March 1933, Butler had to open for the government on the last day of the debate on the Government's proposals for Indian Home Rule. He called for a Joint Select Committee of Both Houses to examine the recent White Paper and make proposals for a bill. Expecting a fierce response from Churchill, he compared himself (29 March) to "a bullock calf tied to a tree, awaiting the arrival of the Lord of the Forest", adding that the tiger would be shot by riflemen when tempted out. Butler was active speaking in the country on behalf of the Union of Britain and India, a front organisation funded by Conservative Central Office and launched on 20 May 1933. Butler faced significant opposition from Conservative Activists in his constituency, including some who deplored the granting of independence to Ireland over a decade earlier and one woman who thought it wrong to give the vote to Indians, as she believed them to be savages who were still fighting with bows and arrows.

Butler opened his memoirs by saying that his career had been split between academia, politics and India, and that his main regret was never having been Viceroy of India. He regarded the 1935 India Act and the 1944 Education Act as his "principal legislative achievements". He also wrote that the way to the top was through rebellion and resignation, whereas he had gone for "the long haul" and "steady influence". In an obvious dig at Home, he said in retirement "I may never have known much about fishing or flower-arranging, but one thing I did know was how to govern the people of this country".

Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister in May 1937. Butler was Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Labour in the new government until February 1938. He served under Ernest Brown, Minister of Labour, who was also responsible for Regional Development, giving Butler experience of the human cost of regional unemployment.

In June 1938 Helmuth Wohlthat, Commissioner for the German Four Year Plan, met Butler and reported that he was favourably-disposed to Germany. Butler spent most of the Sudeten Crisis with Channon at a meeting in Geneva about reform of the Covenant of the League of Nations. He strongly approved of Chamberlain’s trip to Berchtesgaden (16 September), even if it meant sacrificing Czechoslovakia in the interests of peace. Channon recorded Butler as saying (16 September 1938) that “the man in possession when challenged must inevitably part with something”. After Chamberlain’s return from Godesberg, where Hitler had presented inflated demands, Butler’s job was to talk to Maxim Litvinov, Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs. He obtained an assurance (“anodyne” in Jago’s view) that the USSR “would take action” and “might Desire to raise the matter with the League” if Germany acted without agreement.

On 20 October 1939, after the Fall of Poland, Butler was (according to Soviet Ambassador Ivan Maisky) still open to a compromise peace and agreement to restore Germany's colonies to her, provided it was guaranteed by all the powers, including the USA and USSR. He dismissed as an “absurdity” any suggestion that Germany first be required to withdraw from Poland. Butler disapproved of Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty and publicly opposed any hint of compromise peace. After Churchill made a confident war speech on 12 November 1939, not vetted by the Foreign Office and saying that it was "absolutely for certain" that the war must end in the utter defeat either of Britain and France or of Nazi Germany, Butler had to tell the Italian Ambassador (Italy was still neutral) that Churchill was speaking only for himself, not for the government. He told Jock Colville that he "thought it beyond words vulgar". Butler again hoped in vain to be promoted to a ministry of his own on Hore-Belisha’s dismissal (5 January 1940). On 10 and 12 January 1940 Butler strongly opposed “Operation Catherine”, Churchill’s proposal to send a fleet of warships into the Baltic to interdict Swedish iron ore shipments to Germany.

More than half the schools in the country were church schools. However, Church of England schools now educated 20% of children, down from 40% in 1902 (Roman Catholic schools educated 8% of children). Many church schools were in a poor state of repair. The previous President of the Board of Education had produced a "Green Book" of proposals, which had been overtaken by the Five Points demanded by the Protestant Churches (both Anglican and Nonconformist), concerning Christian worship in schools. Butler received a deputation, including the two Anglican Archbishops, on 15 August 1941. There was a five-day debate on education in February 1942. Cosmo Lang, the outgoing Archbishop of Canterbury, spoke in the House of Lords, demanding the Five Points. James Chuter Ede, Butler's junior minister, dissuaded him from bringing in a draft bill to satisfy the Church's demands, as it would prevent a general settlement with other denominations. Temple succeeded the elderly Lang on 1 April 1942. The Church of England had been sympathetic to the "Green Book", but Chuter Ede's new "White Memorandum" aimed to end "single school areas", most of which were in rural districts. Butler had a meeting on 5 June with the National Society (the body of Church of England schools). He proposed that Church schools could choose either to be 50% aided or else fully funded with a local education authority majority on the school governing body. Temple agreed to persuade his flock to accept the deal and later obtained the concession that denominational teachers could be allowed in fully controlled schools if parents so wished. In the end, 3,000 of the 9,000 Anglican schools accepted 50% aided status, not the 500 anticipated. In early October 1942, Butler sold his scheme to the Nonconformist Leaders of England and Wales.

With Churchill's leadership being questioned after recent reverses in the Far East and North Africa, Ivor Bulmer-Thomas (14 August 1942) commented that some Conservative MPs saw Butler rather than Eden as a potential successor. In late November 1942, Butler toyed with the idea of allowing himself to be considered for the job of Viceroy of India (in succession to Lord Linlithgow; Eden had been offered the job by Churchill and was seriously considering accepting it). In the end, Field Marshal Wavell was appointed. Butler helped to write King George VI's Christmas broadcast at the end of 1942.

Butler lobbied John Anderson, Kingsley Wood and Ernest Bevin for an education bill in 1943. By the end of 1942, proposals for a White Paper (a statement of the government's plans, drawn up by civil servants) were proceeding through the Lord President's Committee. In March 1943, with Allied victory (sooner or later) looking increasingly likely, Churchill was now open to the idea of an education bill in 1944. He needed to promise postwar improvements and reforming schools would be cheaper than implementing the Beveridge Report. When the White Paper was published on 16 July 1943, Church-State relations received the least attention whilst Anderson and Wood were happy that the White Paper helped to distract from the Beveridge Report. The resulting bill was produced to a civil Service blueprint. In November 1943, Butler joined the Government Reconstruction Committee. James Stuart (Chief Whip) welcomed the publication of the bill in December 1943, as a way of keeping MPs happy without too much party strife.

Along with the 1944 Education Act and his reforms as Home Secretary, John Campbell sees Butler's greatest achievement as the "redefine(ing of) the meaning of Conservatism" in Opposition, encouraging the careers of talented younger men at the Research Department (Heath, Powell, Maudling, Macleod, Angus Maude, all of whom entered Parliament in 1950) ensuring Conservative acceptance of the welfare state and a commitment to keeping unemployment low. Macmillan acknowledged Butler's role in his memoirs, whilst stressing that these were the very policies he had promoted in vain in the 1930s. Butler enjoyed 26.5 years in office, equalled only by Churchill in the twentieth century.

After the Conservatives were defeated in the 1945 general election, Butler emerged as the most prominent figure in the rebuilding of the party. He became Chairman of the Conservative Research Department, assisted by David Clarke and Michael Fraser. He was opposed to detailed policy-making, not least as he felt the party was not yet pointing in the ideological direction he wanted. In 1946, he became chairman of the Industrial Policy Committee. In 1947, the Industrial Charter was produced, advocating full employment and acceptance of the welfare state (Butler himself said that those who advocated "creating pools of unemployment should be thrown into them and made to swim"). In 1950, he welcomed the "One Nation" pamphlet produced by new MPs including Iain Macleod, Angus Maude, Edward Heath and Enoch Powell.

The Butlers had inherited Gatcombe Park from Sam Courtauld in 1949. In 1976 it was sold to the Queen as a home for Princess Anne, for a sum between £300,000 and £750,000 (Howard gives the figure as "more than £500,000"). He recorded that the Royal Family had driven a hard bargain but joked in public that he was “glad it was going to a good family”.

When the Conservative Party returned to power in 1951, Butler was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. He became Chancellor because Oliver Stanley was dead and Oliver Lyttleton was seen as too linked to Business and the City of London.

Butler maintained import controls and began a more active monetary policy. In his March 1952 budget, Butler raised bank rate to 4% and cut food subsidies by 40% but also cut taxes and increased pensions and welfare payments. Foreign exchange reserves began to increase. In September 1952, Butler was left in charge when Churchill and Eden were both abroad.

The 1953 budget cut income tax and purchase tax and promised an end to the excess profits levy. In the summer of 1953, Butler acted as head of the Government when Churchill suffered a stroke while his presumed successor, Eden, was undergoing an operation overseas. He did not strive to seize the premiership. Between 29 June and 18 August 1953, Butler chaired sixteen Cabinet meetings. In July Macmillan recorded a conversation with Walter Monckton, who was willing to serve under Eden but not Butler, whom he thought "a slab of cold fish". Britain's economic problems at this time were worsened by Monckton's appeasement of the trade unions (e.g. the 1954 rail strike, settled on the union's terms with Churchill's backing) and by Macmillan's drive to build 300,000 houses a year.

In the alternative reality depicted in John Wyndham's short story Random Quest, where the Second World War did not happen, Butler is the prime minister. The story was written in 1954, when Butler acceding to the premiership was a serious possibility.

Jago argues that the Latin tag which Butler applied to Eden, omnium consensu capax imperii nisi imperasset ("by Common consent fit to rule until he ruled"), could have been applied just as accurately to Butler himself. He argues that Butler was possibly the best Chancellor of the Exchequer since the Second World War, but that his achievements were overshadowed by the “pots and pans” budget of 1955, and that he would almost certainly have become Prime Minister had he not destroyed his reputation between April 1955 and January 1957 (his disastrous last budgets, and Suez). Jago believes that “the coup de grace administered seven years later by Macmillan was posthumous”. Jago also argues that his handling of the Central African Federation, even though both Welensky and Ian Smith commented on how ill he was, suggests that he may have been “the best Foreign Secretary Britain never had”. However, Jago also stresses Butler's reputation for chronic indecisiveness, often about petty matters. He argues that he was indecisive as Chancellor, and recounts how during the Profumo Affair he once telephoned a junior civil servant to ask what he should do, as well as occasions on which he was unable to decide on the menu for an official lunch, or whether to attend a reception at the Moroccan Embassy.

On the evening of 6 November 1956, after the British ceasefire had been announced, Butler was observed to be "smiling broadly" on the front bench and astonished some Conservatives by saying that he "would not hesitate to convey" to the absent Prime Minister the concerns which had been expressed by Gaitskell. Eden's press secretary william Clark, an opponent of the policy who along with Edward Boyle (Economic Secretary to the Treasury), resigned as soon as the fighting was over, complained: "God how power corrupts. The way RAB has turned and trimmed." Butler was seen as disloyal because he aired his doubts freely in private whilst supporting the government in public, and he later admitted that he should have resigned. On 14 November, Butler blurted out all that had happened to twenty Conservative MPs of the Progress Trust in a Commons Dining Room (his speech was described by Gilmour as "almost suicidally imprudent").

Butler was less devastated than in 1957, as this time it was largely a voluntary abnegation. In a BBC radio interview in 1978 he discussed that in 1963, he had been passed over in favour of a "terrific gent", not a "most ghastly walrus". Home and even Macmillan, himself in the 1980s, later conceded that it might have been better if Butler had become leader. The episode of Home's elevation was a public relations disaster for the Conservatives, who had to elect their next leader (Edward Heath in 1965) by a transparent ballot of MPs.

Butler had to accept the Home Office under Macmillan, not the Foreign Office which he wanted. In his memoirs, Macmillan claimed that Butler "chose" the Home Office, an assertion of which Butler drily observed in his own memoirs that Macmillan's memory "played him false". Edward Heath corroborates Butler's claim that he had wanted the Foreign Office, and suggested that with his "quiet charm" he could have won over the Americans. Butler also remained Leader of the House of Commons. Early in 1958 he was left "holding the baby", as he put it, after Macmillan departed on a Commonwealth tour after the resignation of Chancellor Thorneycroft and the Treasury team.

Besides the Home Office, Butler held other senior government jobs in these years; he likened himself to the Gilbert and Sullivan character "Pooh Bah". In October 1959, after the 1959 General Election, he was appointed Conservative Party chairman, a job which required him to attack Labour in the country while as Leader of the House he had to cooperate with Labour in the Commons. His new job prompted an analogy (described as "ludicrous" by Anthony Howard) in "The Economist" with Nikita Khrushchev's rise to power through control of the Soviet Communist Party.

In 1960 Macmillan moved Selwyn Lloyd from the Foreign Office to the Exchequer (telling him that it would put him in a good position to challenge Butler for the succession). He appointed Lord Home as Foreign Secretary, refusing again to appoint Butler and telling him that it would be "like Herbert Morrison" if he took the job ("fantastically insulting" in Campbell's view, as Morrison was then regarded as "the worst Foreign Secretary in living memory"). Butler disagreed with the analysis, but accepted it, enabling Macmillan to claim once again that he had declined the Foreign Office (Butler declined to accept Home's old place as Commonwealth Secretary).

In the October 1961 reshuffle Butler lost the party chairmanship to Iain Macleod, who also insisted on getting the job of Leader of the House, which Butler had held since 1955. Butler retained the Home Office, and declined Macmillan's suggestion that he accept a peerage. Butler gave an excellent party conference speech in October 1961. In March 1962 Butler was made head of the newly created Central African Department. Butler was, however, given oversight of the EEC entry negotiations, which he strongly supported, despite worries about the agricultural vote in his constituency. A cartoon showed Macmillan and Butler as the miserable emigrating couple in Ford Madox Brown's painting The Last of England.

However, Macmillan used the occasion to promote younger men such as Lord Hailsham (in charge of negotiating the Test Ban Treaty), Reginald Maudling (Chancellor of the Exchequer, with a remit to reinflate the economy going into the next General Election) and Edward Heath (in charge of the EEC entry negotiations), from amongst whom he hoped to groom an alternative successor. By 1962, Howard writes, "Macmillan had come to regard Rab as a trout that he could tickle and play with at will".

Redmayne's whips had also begun polling MPs and junior ministers at Blackpool, and claimed that 87 supported Home and 86 Butler, another claim ridiculed by Ian Gilmour. 65 MPs were found to be for Hailsham, 48 for Maudling, 12 for Macleod and 10 for Edward Heath, with Home being well ahead on second preferences. Despite denials by the whips, Redmayne let slip in a radio interview (19 December 1963, subsequently published in The Listener) about the four questions they asked: namely, their first and second preferences as leader, whether or not there was any candidate they especially opposed and whether they would in principle accept Home as leader. Humphry Berkeley refused to answer the "hypothetical question" of whether he would support Home as compromise between Butler and Hailsham. Jim Prior (then a backbencher) and Willie Whitelaw (then a junior minister) later recalled how they felt the whips were pushing Home's candidacy. Prior's first choice was Maudling and second Butler, and he opposed Hailsham but suspected he had been recorded as pro-Home after repeated pushing on the fourth question; Whitelaw thought the fourth question "improper".

Butler remained on the Conservative front bench into the next year. Harold Wilson felt that the Conservatives had made Butler a scapegoat after the “Daily Express” incident during the election, and offered him the job of Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, where his great uncle Henry Montagu Butler had previously been Master, on 23 December 1964. Butler did not accept until the middle of January 1965, taking office on 30 June. The same year, he was awarded a life peerage as Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, sitting as a cross-bench peer in the House of Lords. Between the 1964 election and his retirement from the House of Commons he had been Father of the House.

Butler was also active as the first Chancellor of the University of Essex from 1966 until his death and Chancellor of the University of Sheffield from 1959 to 1977. He was High Steward of Cambridge University from 1958 to 1966 and High Steward of the City of Cambridge from 1963 until his death.

The Guardian and the Daily Mirror praised him (on his return to Cambridge in June 1965) but wrote that he had lacked the ruthless streak needed to get to the very top in politics. The Economist (27 June 1970) called him “the last real policy-making Chancellor”.

Butler's memoirs, The Art of the Possible, appeared in 1971. He wrote that he had decided to "eschew the current autobiographical fashion for multi-volume histories" (Macmillan was bringing out an autobiography, which would eventually run to six large volumes). The work, largely ghosted by Peter Goldman, was described as the best single-volume autobiography since Duff Cooper's Old Men Forget in 1953.

From 1972 to 1975, Butler chaired the high-profile Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders, widely referred to as the Butler Committee, which proposed major reforms to the law and psychiatric services, some of which have been implemented.

In June and October 1976 he spoke in the House of Lords against the planned nationalisation of Felixstowe Docks, which are owned by Trinity College. He argued that Trinity, which has had more Nobel Prize winners than the whole of France, spent the income on science research and on subsidising smaller Cambridge colleges. The bill was abandoned after being delayed by the House of Lords. His second term as Master ended in 1977. Butler House at Trinity is named after him.

A further volume of memoirs, The Art of Memory, appeared posthumously in 1982. The latter was modelled on Churchill's Great Contemporaries but in Howard's view matches it "neither in verve nor anecdote".

Lord Chancellor Dilhorne had already begun polling the Cabinet at the Blackpool Conference and claimed that not counting Macmillan or Home, 10 were for Home (including Boyle and Macleod, both of whom later insisted that they supported Butler), 4 for Maudling (originally 3, amended to 5, then down to 4), 3 for Butler and 2 for Hailsham. Ian Gilmour alleged (in his review of Volume II of Horne's official Life of Macmillan in the "London Review of Books", 27 July 1989) that Dilhorne had falsified the figures and repeated his scorn in 2004. Dilhorne recorded Hailsham as saying that he could not serve under Butler; Hailsham in fact claimed that he had offered to serve under Butler if necessary. Frederick Errol, President of the Board of Trade, had been told by Chief Whip Martin Redmayne at Blackpool that the succession was already arranged for Home, as had John Boyd-Carpenter, a Butler supporter, on 9 October.

The Butlers also had a home on the Isle of Mull and, in later years, a flat in Whitehall Court. They bought back Spencers, the old Courtauld family home in Essex where Mollie had previously lived with Augustine Courtauld. Mollie continued living at Spencers after Butler's death in 1982, until her death on 18 February 2009, at the age of 101.

Butler held the Home Office for five years, but his liberal views on hanging and flogging did little to endear him to rank-and-file Conservative members; he later wrote of "Colonel Blimps of both sexes – and the female of the species was more deadly, politically, than the male". Butler later wrote that Macmillan - who kept a tight grip on foreign and economic policies - had given him "a completely free hand" in Home Office matters, which may well be, in Gilmour's view, because reform was likely to blacken Butler in the eyes of Conservative Activists. Macmillan's official biographer believes that he simply had no interest in Home Affairs. Butler later said "I couldn't deal with Eden, but I could deal with Mac".

Butler was able to speak fluent French to French Foreign Minister Maurice Couve de Murville, to the latter’s surprise. His only major foreign trip was to Washington in late March 1964, where President Lyndon Johnson complained about Britain selling Leyland buses to Cuba, whose Castro regime was then under US trade embargo.