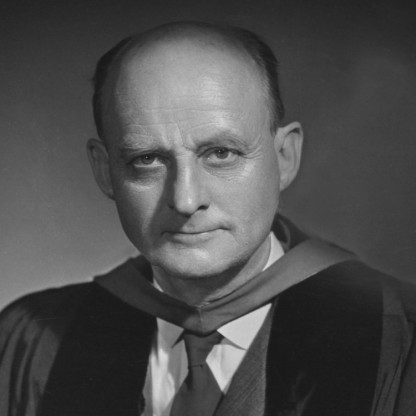

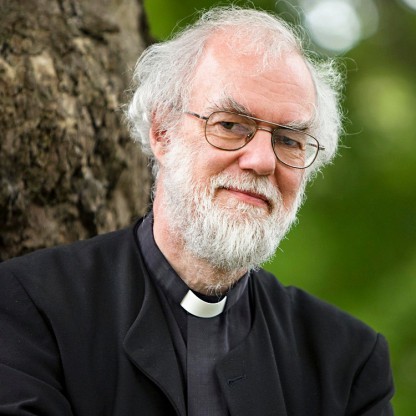

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Theologian |

| Birth Day | June 21, 1892 |

| Birth Place | Wright City, Missouri, United States |

| Age | 127 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 1, 1971(1971-06-01) (aged 78)\nStockbridge, Massachusetts |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Education | Elmhurst College Eden Theological Seminary Yale Divinity School |

| Occupation | Theologian Ethicist Political commentator Minister (1915–28) Professor (1928–60) Magazine editor (1941–66) |

| Years active | 1915–1966 |

| Known for | Christian Realism |

| Spouse(s) | Ursula Niebuhr |

| Children | Christopher Niebuhr Elisabeth Niebuhr Sifton |

| Relatives | H. Richard Niebuhr (brother) Hulda Niebuhr (sister) Walter Niebuhr (brother) |

Net worth: $8 Million (2024)

Reinhold Niebuhr, a renowned theologian in the United States, is estimated to have a net worth of $8 million by 2024. Born in 1892, Niebuhr made significant contributions to the field of Christian ethics and political thought throughout his lifetime. His influential writings and teachings on the complexities of human nature and the morality of power have earned him a prominent position in the theological realm. As an author, speaker, and professor, Niebuhr's intellectual work continues to resonate with scholars and individuals alike, shaping the discourse on ethics and politics. With his wealth and enduring legacy, Reinhold Niebuhr has left an indelible impact on the theological landscape of the United States.

Famous Quotes:

We went through one of the big automobile factories to-day.... The foundry interested me particularly. The heat was terrific. The men seemed weary. Here manual labour is a drudgery and toil is slavery. The men cannot possibly find any satisfaction in their work. They simply work to make a living. Their sweat and their dull pain are part of the price paid for the fine cars we all run. And most of us run the cars without knowing what price is being paid for them.... We are all responsible. We all want the things which the factory produces and none of us is sensitive enough to care how much in human values the efficiency of the modern factory costs.

Biography/Timeline

Niebuhr was born in Wright City, Missouri, the son of German immigrants Gustav Niebuhr, and his wife, Lydia (née Hosto). His father was a German Evangelical pastor; his denomination was the American branch of the established Prussian Church Union in Germany. It is now part of the United Church of Christ. The family spoke German at home. His brother H. Richard Niebuhr also became a famous theological ethicist, and his sister Hulda Niebuhr became a divinity professor in Chicago. The Niebuhr family moved to Lincoln, Illinois, in 1902 when Gustav Niebuhr became pastor of Lincoln's St. John's German Evangelical Synod church. Reinhold Niebuhr first served as pastor of a church when he served from April to September 1913 as interim minister of St. John's following his father's death.

Niebuhr attended Elmhurst College in Illinois and graduated in 1910. He studied at Eden Theological Seminary in Webster Groves, Missouri, where, as he admitted, he was deeply influenced by Samuel D. Press in "biblical and systematic subjects", and Yale Divinity School, where he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1914 and a Master of Arts degree the following year. He always regretted not taking a doctorate. He said that Yale gave him intellectual liberation from the localism of his German-American upbringing.

In 1915, Niebuhr was ordained a pastor. The German Evangelical mission board sent him to serve at Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit, Michigan. The congregation numbered sixty-six on his arrival and grew to nearly 700 by the time he left in 1928. The increase reflected his ability to reach people outside the German American community and among the growing population attracted to jobs in the booming automobile industry. In the early 1900s Detroit became the fourth-largest city in the country, attracting many black and white migrants from the rural South, as well as Jewish and Catholic ethnics from eastern and southern Europe. They competed for jobs and limited housing, and the city's rapid changes and rise in social tensions contributed to the growth in numbers of Ku Klux Klan members in the city, which reached its peak in 1925, and to the Black Legion. During that year's city election campaign, in which the Klan publicly supported several candidates, including for the office of mayor, Niebuhr spoke out publicly against the Klan to his congregation, describing them as "one of the worst specific social phenomena which the religious pride of a people has ever developed". Only one of their several candidates gained a seat on the city council, and Charles Bowles, the mayoral candidate, was defeated.

As America entered the World War in 1917, Niebuhr was the unknown pastor of a small German-speaking congregation in Detroit (it stopped using German in 1919). All German American culture in the United States and nearby Canada came under attack for suspicion of having dual loyalties. Niebuhr repeatedly stressed the need to be loyal to America, and won an audience in national magazines for his appeals to the German Americans to be patriotic. Theologically, he went beyond the issue of national loyalty as he endeavored to fashion a realistic ethical perspective of patriotism and pacifism. He endeavored to work out a realistic approach to the moral danger posed by aggressive powers, which many Idealists and pacifists failed to recognize. During the war, he also served his denomination as Executive Secretary of the War Welfare Commission, while maintaining his pastorate in Detroit. A pacifist at heart, he saw compromise as a necessity and was willing to support war in order to find peace—compromising for the sake of righteousness.

Anti-Catholicism surged in Detroit in the 1920s in reaction to the rise in the number of Catholic immigrants from southern Europe since the early 20th century. It was exacerbated by the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, which recruited many members in Detroit. Niebuhr defended pluralism by attacking the Klan. During the Detroit mayoral election of 1925, Niebuhr's sermon, "We fair-minded Protestants cannot deny", was published on the front pages of both the Detroit Times and the Free Press.

In 1923, Niebuhr visited Europe to meet with intellectuals and Theologians. The conditions he saw in Germany under the French occupation of the Rhineland dismayed him. They reinforced the pacifist views that he had adopted throughout the 1920s after World War I.

Niebuhr debated Charles Clayton Morrison, Editor of The Christian Century magazine, about America's entry into World War II. Morrison and his pacifistic followers maintained that America's role should be strictly neutral and part of a negotiated peace only, while Niebuhr claimed himself to be a realist, who opposed the use of political power to attain moral ends. Morrison and his followers strongly supported the movement to outlaw war that began after World War I and the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928. The pact was severely challenged by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. With his publication of Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932), Niebuhr broke ranks with The Christian Century and supported interventionism and power politics. He supported the reelection of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940 and published his own magazine, Christianity and Crisis. In 1945, however, Niebuhr charged that use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was "morally indefensible".

During the 1930s, Niebuhr was a prominent leader of the militant faction of the Socialist Party of America, although he disliked die-hard Marxists. He described their beliefs as a religion and a thin one at that. In 1941, he co-founded the Union for Democratic Action, a group with a strongly militarily interventionist, internationalist foreign policy and a pro-union, liberal domestic policy. He was the group's President until it transformed into the Americans for Democratic Action in 1947.

In 1931 Niebuhr married Ursula Keppel-Compton. She was a member of the Church of England and was educated at Oxford University in theology and history. She met Niebuhr while studying for her master's degree at Union Theological Seminary. For many years, she was on faculty at Barnard College (the women's college of Columbia University) where she helped establish and then chaired the religious studies department. The Niebuhrs had two children, Christopher Niebuhr and Elisabeth Niebuhr Sifton. Ursula Niebuhr left evidence in her professional papers at the Library of Congress showing that she co-authored some of her husband's later writings.

As a young pastor in Detroit, he favored conversion of Jews to Christianity, scolding evangelical Christians who were anti-Semitic or ignoring them. He spoke out against "the unchristlike attitude of Christians" and what he described as his fellow Christians' "Jewish bigotry". His 1933 article in the Christian Century was an attempt to sound the alarm within the Christian community over Hitler's "cultural annihilation of the Jews". Eventually his theology evolved to the point where he was the first prominent Christian theologian to argue it was inappropriate for Christians to seek to convert Jews to their faith.

Niebuhr captured his personal experiences in Detroit in his book Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic. He continued to write and publish throughout his career, and also served as Editor of the magazine Christianity and Crisis from 1941 through 1966.

As a preacher, Writer, leader, and adviser to political figures, Niebuhr supported Zionism and the development of Israel. His solution to anti-Semitism was a combination of a Jewish homeland, greater tolerance, and assimilation in other countries. As early as 1942, he advocated the expulsion of Arabs from Palestine and their resettlement in other Arab countries. His position may have related to his religious conviction that life on earth is imperfect, and his concern about German anti-Semitism.

In his last cover story for Time magazine (March 1948), Whittaker Chambers said of Niebuhr:

In the 1950s, Niebuhr described Senator Joseph McCarthy as a force of evil, not so much for attacking civil liberties, as for being ineffective in rooting out Communists and their sympathizers. In 1953, he supported the execution of the Rosenbergs, saying, "Traitors are never ordinary Criminals and the Rosenbergs are quite obviously fiercely loyal Communists... Stealing atomic secrets is an unprecedented crime."

In 1952, Niebuhr published The Irony of American History, in which he interpreted the meaning of the United States' past. Niebuhr questioned whether a humane, "ironical" interpretation of American history was credible on its own merits, or only in the context of a Christian view of history. Niebuhr's concept of irony referred to situations in which "the consequences of an act are diametrically opposed to the original intention", and "the fundamental cause of the disparity lies in the actor himself, and his original purpose." His reading of American history based on this notion, though from the Christian perspective, is so rooted in historical events that readers who do not share his religious views can be led to the same conclusion. Niebuhr's great foe was idealism. American idealism, he believed, comes in two forms: the idealism of the antiwar non-interventionists, who are embarrassed by power; and the idealism of pro-war imperialists, who disguise power as virtue. He said the non-interventionists, without mentioning Harry Emerson Fosdick by name, seek to preserve the purity of their souls, either by denouncing military actions or by demanding that every action taken be unequivocally virtuous. They exaggerate the sins committed by their own country, excuse the malevolence of its enemies and, as later polemicists have put it, inevitably blame America first. Niebuhr argued this approach was a pious way to refuse to face real problems.

While after World War II most liberals endorsed integration, Niebuhr focused on achieving equal opportunity. He warned against imposing changes that could result in violence. The violence that followed peaceful demonstrations in the 1960s forced Niebuhr to reverse his position against imposed equality; witnessing the problems of the Northern ghettos later caused him to doubt that equality was attainable.

In the "Letter from Birmingham Jail" Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, "Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals." King drew more heavily upon Niebuhr's social and ethical ideals than on anyone else (including Gandhi). King invited Niebuhr to participate in the third Selma to Montgomery March in 1965, and Niebuhr responded by telegram: "Only a severe stroke prevents me from accepting ... I hope there will be a massive demonstration of all the citizens with conscience in favor of the elemental human rights of voting and freedom of assembly" (Niebuhr, March 19, 1965). Two years later, Niebuhr defended King's decision to speak out against the Vietnam War, calling him "one of the greatest religious Leaders of our time". Niebuhr asserted: "Dr. King has the right and a duty, as both a religious and a civil rights leader, to express his concern in these days about such a major human Problem as the Vietnam War." Of his country's intervention in Vietnam, Niebuhr admitted: "For the first time I fear I am ashamed of our beloved nation."

Niebuhr's influence was at its peak during the first two decades of the Cold War. By the 1970s, his influence was declining because of the rise of liberation theology, antiwar sentiment, the growth of conservative evangelicalism, and postmodernism. According to Historian Gene Zubovich, "It took the tragic events of September 11, 2001, to revive Niebuhr."

In more recent years, Niebuhr has enjoyed something of a renaissance in contemporary thought, although usually not in liberal Protestant theological circles. Both major-party candidates in the 2008 presidential election cited Niebuhr as an influence: Senator John McCain, in his book Hard Call, "celebrated Niebuhr as a paragon of clarity about the costs of a good war". President Barack Obama said that Niebuhr was his "favorite philosopher" and "favorite theologian". Slate magazine columnist Fred Kaplan characterized Obama's 2009 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech a "faithful reflection" of Niebuhr.

Niebuhr claimed he wrote the short Serenity Prayer. Fred R. Shapiro, who had cast doubts on Niebuhr's claim, conceded in 2009 that, "The new evidence does not prove that Reinhold Niebuhr wrote [the prayer], but it does significantly improve the likelihood that he was the originator." The earliest known version of the prayer, from 1937, attributes the prayer to Niebuhr in this version:

After Joseph Stalin signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Adolf Hitler in August 1939, Niebuhr severed his past ties with any fellow-traveler organization having any known Communist leanings. In 1947, Niebuhr helped found the liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA). His ideas influenced George Kennan, Hans Morgenthau, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and other realists during the Cold War on the need to contain Communist expansion.

Niebuhr argued that to approach religion as the individualistic attempt to fulfill biblical commandments in a moralistic sense is not only an impossibility but also a demonstration of man's original sin, which Niebuhr interpreted as self-love. Through self-love man becomes focused on his own goodness and leaps to the false conclusion—one he called the "Promethean illusion"—that he can achieve goodness on his own. Thus man mistakes his partial ability to transcend himself for the ability to prove his absolute authority over his own life and world. Constantly frustrated by natural limitations, man develops a lust for power which destroys him and his whole world. History is the record of these crises and judgments which man brings on himself; it is also proof that God does not allow man to overstep his possibilities. In radical contrast to the Promethean illusion, God reveals himself in history, especially personified in Jesus Christ, as sacrificial love which overcomes the human temptation to self-deification and makes possible constructive human history.

In spring of 2017, it was speculated (and later confirmed) that former FBI Director James Comey used Niebuhr's name as a screen name for his personal Twitter account. Comey, as a religion major at the College of william & Mary, wrote his undergraduate thesis on Niebuhr and televangelist Jerry Falwell.