Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Composer |

| Birth Day | June 11, 1864 |

| Birth Place | Munich, German |

| Age | 155 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 8 September 1949(1949-09-08) (aged 85)\nGarmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany |

| Birth Sign | Cancer |

| Occupation | Composer |

Net worth

Richard Georg Strauss, a renowned German composer, is estimated to have a net worth ranging from $100,000 to $1 million in the year 2024. As a highly influential figure in classical music, Strauss is recognized for his exceptional compositions and contributions to the genre. Known for his complex orchestral works and operas, he has left an indelible mark on the music industry, and his creations are still celebrated and performed today. With such a substantial net worth, Richard Georg Strauss' legacy and impact on music will continue to be commemorated for years to come.

Famous Quotes:

It is true, as the critics suggest, that the readings forego overt emotion, but what emerges instead is a solid sense of structure, letting the music speak convincingly for itself. It is also true that Strauss's tempos are generally swift, but this, too, contributes to the structural cohesion and in any event is fully in keeping with our modern outlook in which speed is a virtue and attention spans are defined more by MTV clips and news sound bites than by evenings at the opera and thousand page novels.

Biography/Timeline

Strauss was born on 11 June 1864 in Munich, the son of Josephine (née Pschorr) and Franz Strauss, who was the principal horn player at the Court Opera in Munich. In his youth, he received a thorough musical education from his father. He wrote his first composition at the age of six, and continued to write music almost until his death.

During his boyhood Strauss attended orchestra rehearsals of the Munich Court Orchestra (now the Bavarian State Orchestra), where he received private instruction in music theory and orchestration from an assistant Conductor. In 1872, he started receiving violin instruction at the Royal School of Music from Benno Walter, his father's cousin. In 1874, Strauss heard his first Wagner operas, Lohengrin and Tannhäuser. The influence of Wagner's music on Strauss's style was to be profound, but at first his musically conservative father forbade him to study it. Indeed, in the Strauss household, the music of Richard Wagner was viewed with deep suspicion, and it was not until the age of 16 that Strauss was able to obtain a score of Tristan und Isolde. In later life, Strauss said that he deeply regretted the conservative hostility to Wagner's progressive works. Nevertheless, Strauss's father undoubtedly had a crucial influence on his son's developing taste, not least in Strauss's abiding love for the horn.

Some of Strauss's first compositions were solo instrumental and chamber works. These pieces include early compositions for piano solo in a conservative harmonic style, many of which are lost: two piano trios (1877 and 1878), a string quartet (1881), a piano sonata (1882), a cello sonata (1883), a piano quartet (1885), a violin sonata (1888), as well as a serenade (1882) and a longer suite (1884), both scored for double wind quintet plus two additional horns and contrabassoon.

Strauss wrote two early symphonies: Symphony No. 1 (1880) and Symphony No. 2 (1884). However, Strauss's style began to truly develop and change when, in 1885, he met Alexander Ritter, a noted Composer and Violinist, and the husband of one of Richard Wagner's nieces. It was Ritter who persuaded Strauss to abandon the conservative style of his youth and begin writing tone poems. He also introduced Strauss to the essays of Wagner and the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer. Strauss went on to conduct one of Ritter's operas, and at Strauss's request Ritter later wrote a poem describing the events depicted in Strauss's tone poem Death and Transfiguration.

In early 1882, in Vienna, he gave the first performance of his Violin Concerto in D minor, playing a piano reduction of the orchestral part himself, with his Teacher Benno Walter as soloist. The same year he entered Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where he studied philosophy and art history, but not music. He left a year later to go to Berlin, where he studied briefly before securing a post as assistant Conductor to Hans von Bülow, who had been enormously impressed by the young composer's Serenade for wind instruments, composed when he was only 16 years of age. Strauss learned the art of conducting by observing Bülow in rehearsal. Bülow was very fond of the young man, and decided that Strauss should be his successor as Conductor of the Meiningen Court Orchestra when Bülow resigned in 1885. Strauss's compositions at this time were indebted to the style of Robert Schumann or Felix Mendelssohn, true to his father's teachings. His Horn Concerto No. 1, Op. 11, is representative of this period and is a staple of the modern horn repertoire.

The new influences from Ritter resulted in what is widely regarded as Strauss's first piece to show his mature personality, the tone poem Don Juan (1888), which displays a new kind of virtuosity in its bravura orchestral manner. Strauss went on to write a series of increasingly ambitious tone poems: Death and Transfiguration (1889), Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks (1895), Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1896), Don Quixote (1897), Ein Heldenleben (1898), Symphonia Domestica (1903) and An Alpine Symphony (1911–1915). One commentator has observed of these works that "no orchestra could exist without his tone poems, written to celebrate the glories of the post-Wagnerian symphony orchestra."

After 1890, Strauss composed very infrequently for chamber groups, his energies being almost completely absorbed with large-scale orchestral works and operas. Four of his chamber pieces are actually arrangements of portions of his operas, including the Daphne-Etude for solo violin and the String Sextet, which is the overture to his final opera Capriccio. His last independent chamber work, an Allegretto in E major for violin and piano, dates from 1948.

James Hepokoski notes a shift in Strauss's technique in the tone poems, occurring between 1892 and 1893. It was after this point that Strauss rejected the philosophy of Schopenhauer and began more forcefully critiquing the institution of the symphony and the symphonic poem, thereby differentiating the second cycle of tone poems from the first.

Around the end of the 19th century, Strauss turned his attention to opera. His first two attempts in the genre, Guntram (1894) and Feuersnot (1901), were controversial works: Guntram was the first significant critical failure of Strauss's career, and Feuersnot was considered obscene by some critics.

The Strausses had one son, Franz, in 1897. Franz married Alice von Grab-Hermannswörth, daughter of a Jewish industrialist, in a Roman Catholic ceremony in 1924. Franz and Alice had two sons, Richard and Christian.

Strauss's music had a considerable influence on composers at the start of the 20th century. Béla Bartók heard Also sprach Zarathustra in 1902, and later said that the work "contained the seeds for a new life"; a Straussian influence is clearly present in his works of that period, including his First String Quartet, Kossuth, and Bluebeard's Castle. Karol Szymanowski was also greatly influenced by Strauss, reflected in such pieces as his Concert Overture and his first and second symphonies, and his opera Hagith which was modeled after Salome. English composers were also influenced by Strauss, from Edward Elgar in his concert overture In the South (Alassio) and other works to Benjamin Britten in his opera writing. Many contemporary composers recognise a debt to Strauss, including John Adams and John Corigliano.

In 1905, Strauss produced Salome, a somewhat dissonant modernist opera based on the play by Oscar Wilde, which produced a passionate reaction from audiences. The premiere was a major success, with the artists taking more than 38 curtain calls. Many later performances of the opera were also successful, not only with the general public but also with Strauss's peers: Maurice Ravel said that Salome was "stupendous", and Gustav Mahler described it as "a live volcano, a subterranean fire". Strauss reputedly financed his house in Garmisch-Partenkirchen completely from the revenues generated by the opera. As with the later Elektra, Salome features an incredibly taxing lead Soprano role. Strauss often remarked that he preferred writing for the female voice, which is apparent in these two sister operas—the male parts are almost entirely smaller roles, included only to supplement the soprano's performance.

Strauss also made live-recording player piano music rolls for the Hupfeld system and in 1906 ten recordings for the reproducing piano Welte-Mignon all of which survive today. Strauss was also the Composer of the music on the first CD to be commercially released: Deutsche Grammophon's 1983 release of their 1980 recording of Herbert von Karajan conducting the Alpine Symphony.

Strauss's next opera was Elektra (1909), which took his use of dissonance even further, in particular with the Elektra chord. Elektra was also the first opera in which Strauss collaborated with the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal. The two subsequently worked together on numerous occasions. For his later works with Hofmannsthal, Strauss moderated his harmonic language: he used a more lush, melodic late-Romantic style based on Wagnerian chromatic harmonies that he had used in his tone poems, with much less dissonance, and exhibiting immense virtuosity in orchestral writing and tone color. This resulted in operas such as Der Rosenkavalier (1911) having great public success. Strauss continued to produce operas at regular intervals until 1942. With Hofmannsthal he created Ariadne auf Naxos (1912), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), Die ägyptische Helena (1928), and Arabella (1933). For Intermezzo (1924) Strauss provided his own libretto. Die schweigsame Frau (1935), was composed with Stefan Zweig as librettist; Friedenstag (1935–6) and Daphne (1937) both had a libretto by Joseph Gregor and Stefan Zweig; and Die Liebe der Danae (1940) was with Joseph Gregor. Strauss's final opera, Capriccio (1942), had a libretto by Clemens Krauss, although the genesis for it came from Stefan Zweig and Joseph Gregor.

Koch Legacy has also released Strauss's recordings of overtures by Gluck, Carl Maria von Weber, Peter Cornelius, and Wagner. The preference for German and Austrian composers in Germany in the 1920s through the 1940s was typical of the German nationalism that existed after World War I. Strauss clearly capitalized on national pride for the great German-speaking composers.

Strauss, as Conductor, made a large number of recordings, both of his own music as well as music by German and Austrian composers. His 1929 performances of Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks and Don Juan with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra have long been considered the best of his early electrical recordings. In the first complete performance of his An Alpine Symphony, made in 1941 and later released by EMI, Strauss used the full complement of percussion instruments required in this work.

There were many other recordings, including some taken from radio broadcasts and concerts during the 1930s and early 1940s. The sheer volume of recorded performances would undoubtedly yield some definitive performances from a very capable and rather forward-looking Conductor.

Strauss privately scorned Goebbels and called him "a pipsqueak". However, in 1933 he dedicated an orchestral song, "Das Bächlein" ("The Little Brook"), to Goebbels, in order to gain his cooperation in extending German music copyright laws from 30 years to 50 years.

This letter to Zweig was intercepted by the Gestapo and sent to Hitler. Strauss was subsequently dismissed from his post as Reichsmusikkammer President in 1935. The 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics nevertheless used Strauss's Olympische Hymne, which he had composed in 1934. Strauss's seeming relationship with the Nazis in the 1930s attracted criticism from some noted Musicians, including Arturo Toscanini, who in 1933 had said, "To Strauss the Composer I take off my hat; to Strauss the man I put it back on again", when Strauss had accepted the presidency of the Reichsmusikkammer. Much of Strauss's motivation in his conduct during the Third Reich was, however, to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice and his Jewish grandchildren from persecution. Both of his grandsons were bullied at school, but Strauss used his considerable influence to prevent the boys or their mother being sent to concentration camps.

When his Jewish daughter-in-law Alice was placed under house arrest in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1938, Strauss used his connections in Berlin, including opera-house General Intendant Heinz Tietjen, to secure her safety. He drove to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in order to argue, albeit unsuccessfully, for the release of Alice's grandmother, Paula Neumann. In the end, Neumann and 25 other relatives were murdered in the camps. While Alice's mother, Marie von Grab, was safe in Lucerne, Switzerland, Strauss also wrote several letters to the SS pleading for the release of her children who were also held in camps; his letters were ignored.

Pierre Boulez has said that Strauss the Conductor was "a complete master of his trade". Music critic Harold C. Schonberg writes that, while Strauss was a very fine Conductor, he often put scant effort into his recordings. Schonberg focused primarily on Strauss's recordings of Mozart's Symphony No. 40 and Beethoven's Symphony No. 7, as well as noting that Strauss played a breakneck version of Beethoven's 9th Symphony in about 45 minutes. Concerning Beethoven's 7th Symphony, Schonberg wrote, "There is almost never a ritard or a change in expression or nuance. The slow movement is almost as fast as the following vivace; and the last movement, with a big cut in it, is finished in 4 minutes, 25 seconds. (It should run between 7 and 8 minutes.)" He also complained that the Mozart symphony had "no force, no charm, no inflection, with a metronomic rigidity."

The metaphor "Indian Summer" is often used by journalists, biographers, and music critics to describe Strauss's late creative upsurge from 1942 to the end of his life. The events of World War II seemed to bring the composer—who had grown old, tired, and a little jaded—into focus. The major works of the last years of Strauss's life, written in his late 70s and 80s, include, among others, his Horn Concerto No. 2, Metamorphosen, his Oboe Concerto, and his Four Last Songs.

He also composed two large-scale works for wind ensemble during this period: Sonatina No. 1 "From an Invalid's Workshop" (1943) and Sonatina No. 2 "Happy Workshop" (1946)—both scored for double wind quintet plus two additional horns, a third clarinet in C, bassett horn, bass clarinet, and contrabassoon.

In April 1945, Strauss was apprehended by American Soldiers at his Garmisch estate. As he descended the staircase he announced to Lieutenant Milton Weiss of the U.S. Army, "I am Richard Strauss, the Composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome." Lt. Weiss, who was also a musician, nodded in recognition. An "Off Limits" sign was subsequently placed on the lawn to protect Strauss. The American oboist John de Lancie, who knew Strauss's orchestral writing for oboe thoroughly, was in the army unit, and asked Strauss to compose an oboe concerto. Initially dismissive of the idea, Strauss completed this late work, his Oboe Concerto, before the end of the year.

In 1944, Strauss celebrated his 80th birthday and conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in recordings of his own major orchestral works, as well as his seldom-heard Schlagobers (Whipped Cream) ballet music. Some find more feeling in these performances than in Strauss's earlier recordings, which were recorded on the Magnetophon tape recording equipment. Vanguard Records later issued the recordings on LPs. Some of these recordings have been reissued on CD by Preiser. The last recording made by Strauss was on 19 October 1947 live at the Royal Albert Hall in London, where he conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra in his Burleske for piano and orchestra (Alfred Blumen piano), Don Juan and Sinfonia Domestica.

Strauss produced Lieder throughout his career. The Four Last Songs are among his best known, along with "Ruhe, meine Seele!", "Cäcilie", "Morgen!", "Heimliche Aufforderung", "Traum durch die Dämmerung", and others. In 1948, Strauss wrote his last work, the Four Last Songs for Soprano and orchestra. He reportedly composed them with Kirsten Flagstad in mind and she gave the first performance, which was recorded. Strauss's songs have always been popular with audiences and performers, and are generally considered by musicologists—along with many of his other compositions—to be masterpieces.

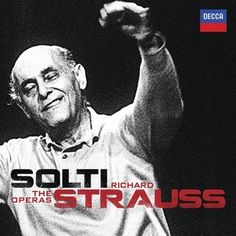

Soon after the Munich celebrations of the composer's 85th birthday, Strauss began to suffer from heart failure. He died at the age of 85 on 8 September 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, West Germany. Georg Solti, who had arranged Strauss's 85th birthday celebration, also directed an orchestra during Strauss's burial. The Conductor later described how, during the singing of the famous trio from Rosenkavalier, "each singer broke down in tears and dropped out of the ensemble, but they recovered themselves and we all ended together." Strauss's wife, Pauline de Ahna, died eight months later, on 13 May 1950, at the age of 88.

Strauss's musical style played a major role in the development of film music in the middle of the 20th century. The style of his musical depictions of character (Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel, the Hero) and emotions found their way into the lexicon of film music. Film music Historian Timothy Schuerer wrote, "The elements of post (late) romantic music that had greatest impact on scoring are its lush sound, expanded harmonic language, chromaticism, use of program music and use of Leitmotifs. Hollywood composers found the post-romantic idiom compatible with their efforts in scoring film". Max Steiner and Erich Korngold came from the same musical world as Strauss and were quite naturally drawn to write in his style. As film Historian Roy Prendergast wrote, "When confronted with the kind of dramatic Problem films presented to them, Steiner, Korngold and Newman ... looked to Wagner, Puccini, Verdi and Strauss for the answers to dramatic film scoring." Later, the opening to Also sprach Zarathustra became one of the best known pieces of film music when Stanley Kubrick used it in his 1968 movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film music of John Williams has continued the Strauss influence, in scores for mainstream hits such as Superman and Star Wars.

Until the 1980s, Strauss was regarded by some post-modern musicologists as a conservative, backward-looking Composer, but re-examination of and new research on the Composer has re-evaluated his place as that of a modernist, albeit one who still utilized and sometimes revered tonality and lush orchestration. Strauss is noted for his pioneering subtleties of orchestration, combined with an advanced harmonic style; when he first played Strauss at a university production of Ariadne auf Naxos, the Conductor Mark Elder "was flabbergasted. I had no idea music could do the things he was doing with harmony and melody."

Peter Gutmann's 1994 review for ClassicalNotes.com says the performances of the Beethoven 5th and 7th symphonies, as well as Mozart's last three symphonies, are actually quite good, even if they are sometimes unconventional. Gutmann wrote:

Strauss has always been popular with audiences in the concert hall and continues to be so. He has consistently been in the top 10 composers most performed by symphony orchestras in the US and Canada over the period 2002–10. He is also in the top 5 of 20th Century composers (born after 1860) in terms of the number of currently available recordings of his works.

According to statistics compiled by Operabase, in number of operas performed worldwide over the five seasons from 2008/09 to 2012/13, Strauss was the second-most performed 20th-century opera Composer, ahead of Benjamin Britten and behind only Giacomo Puccini. Strauss tied with Handel as the eighth most-performed opera Composer from any century over those five seasons. Over the five seasons from 2008/09 to 2012/13, Strauss's top five most-performed operas were Salome, Ariadne auf Naxos, Der Rosenkavalier, Elektra, and Die Frau ohne Schatten. The most recent figures covering the five seasons 2011/12 to 2015/2016 show that Strauss was the tenth most performed opera Composer, with Der Rosenkavalier overtaking Salome to become his most performed opera (the ranking of the other four remains the same).

The Four Last Songs, composed shortly before Strauss's death, deal with the subject of dying. The last one, "Im Abendrot" (At Sunset), ends with the line "Is this perhaps death?" The question is not answered in words, but instead Strauss quotes the "transfiguration theme" from his earlier tone poem, Death and Transfiguration—meant to symbolize the transfiguration and fulfilment of the soul after death.