Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | A Freak Show Attraction |

| Birth Year | 1789 |

| Birth Place | Gamtoos River, Kouga Local Municipality, South Africa, South African |

| Age | 230 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 1815 (aged 26)\nParis, France |

| Resting place | Vergaderingskop, Hankey, Eastern Cape, South Africa 33°50′14″S 24°53′05″E / 33.8372°S 24.8848°E / -33.8372; 24.8848Coordinates: 33°50′14″S 24°53′05″E / 33.8372°S 24.8848°E / -33.8372; 24.8848 |

| Other names | Hottentot Venus, Saartjie Baartman |

Net worth: $700,000 (2024)

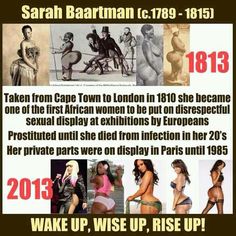

Sarah Baartman's net worth is estimated to be $700,000 in 2024. However, it is essential to recognize that monetary value does not define the historical significance of individuals, especially in the case of Sarah Baartman. Known as a deeply unsettling example of exploitation and racism, Sarah Baartman was tragically exhibited as a freak show attraction in South Africa during the early 19th century. Her objectification and mistreatment reflect the dehumanizing nature of the time, highlighting the necessity for social progress and the fight against discrimination. Remembering Sarah Baartman's story is vital for promoting equality and respect for all individuals, regardless of their background or physical appearance.

Famous Quotes:

Her first name is the Cape Dutch form for "Sarah" which marked her as a colonialist's servant. "Saartje" the diminutive, was also a sign of affection. Encoded in her first name were the tensions of affection and exploitation. Her surname literally means "bearded man" in Dutch. It also means uncivilized, uncouth, barbarous, savage. Saartjie Baartman – the savage servant.

Biography/Timeline

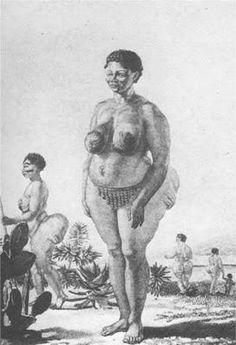

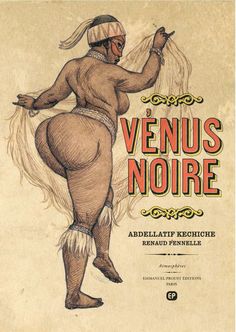

Sarah Baartman, called "Saartjie" (the diminutive form), was likely born in 1789 in the Gamtoos valley in the eastern part of the Cape Colony. In 1810, she went to England with her employer, a free black man (a Cape designation for someone of slave descent) called Hendrik Cesars, and william Dunlop, an English Doctor who worked at the Cape slave lodge. They sought to show her for money on the London stage. Sara Baartman spent four years on stage in England and Ireland. Early on, her treatment on the Piccadilly stage caught the attention of British abolitionists, who argued that her performance was indecent and that she was being forced to perform against her will. Ultimately, the court ruled in favour of her exhibition after Dunlop produced a contract made between himself and Baartman. It is doubtful that this contract was valid: it was probably produced for the purposes of the trial. Cesars left the show and Dunlop continued to display Baartman in country fairs. Baartman also moved to Manchester where she was baptized as Sarah Bartmann. In 1814, after Dunlop's death, a man called Henry Taylor brought Baartman to Paris. He sold her to an animal trainer, S. Reaux, who made her amuse onlookers who frequented the Palais-Royal. Georges Cuvier, founder and professor of comparative anatomy at the Museum of Natural History examined Baartman as he searched for proof of a so-called missing link between animals and human beings. Baartman's body was exploited for scientific racism. Baartman lived in poverty, and died in Paris of an undetermined inflammatory disease in December 1815. After her death, Cuvier dissected her body, and displayed her remains. For more than a century and a half, visitors to the Museum of Man in Paris could view her brain, skeleton and genitalia as well as a plaster cast of her body. Her remains were returned to South Africa in 2002 and she was buried in the Eastern Cape on South Africa's National Women's Day.

Baartman spent her childhood and teenage years on settler farms. She went through puberty rites, and kept the small tortoise shell necklace, probably given to her by her mother, until her death in France. In the 1790s, a free black (the Cape designation for individuals of enslaved descent) trader named Peter Cesars met her and encouraged her to move to Cape Town, which had recently come under British control. Records do not show whether she was made to leave, or went willingly, or was sent by her family to Cesars. She lived in Cape Town for at least two years working in households as a washerwoman and a nursemaid, first for Peter Cesars, then in the house of a Dutch man in Cape Town. She moved finally to be a wet-nurse in the household of Peter Cesars' brother-in-law, Hendrik Cesars, outside of Cape Town in present day Woodstock. Sara Baartman lived alongside slaves in the Cesars' household. As someone of Khoisan descent she could not be formally enslaved, but probably lived in conditions similar to slaves in Cape Town. There is evidence that she had two children, though both died as babies. She had a relationship with a poor European military man, Hendrik Van Jong, who lived in Hout Bay near Cape Town, but the relationship ended when his regiment left the Cape. william Dunlop, a Scottish military surgeon in the Cape slave lodge, with a sideline in supplying showmen in Britain with animal specimens, suggested she travel to England to make money by exhibition. Baartman refused. Dunlop persisted and Sara Baartman said she would only go if Hendrik Cesars came too. He also refused, but became ever more in debt in part because of unfavorable lending terms because of his status as free black. Finally, in 1810 he agreed to go to England to make money through putting Sara Baartman on stage. The party left for London in 1810. It is unknown if Sara Baartman went willingly or was forced, but she was in no position to refuse even if she chose to do so.

Her exhibition in London just a few years after the passing of the Slave Trade Act 1807 created a scandal. This is in part because British audiences misread Hendrik Cesars, thinking he was a Dutch farmer, boer, from the frontier. Scholars have tended to reproduce that error, but tax rolls at the Cape show he was free black. Violence was part of the show. An abolitionist benevolent society called the African Association conducted a newspaper campaign for her release. Zachary Macaulay led the protest. Hendrik Cesars protested that Baartman was entitled to earn her living, stating: "has she not as good a right to exhibit herself as an Irish Giant or a Dwarf?" Cesars was comparing Baartman to the contemporary Irish giants Charles Byrne and Patrick Cotter O'Brien. Macaulay and The African Association took the matter to court and on November 24, 1810 at the Court of King's Bench the Attorney-General began the attempt "to give her liberty to say whether she was exhibited by her own consent." In support he produced two affidavits in court. The first, from a Mr Bullock of Liverpool Museum, was intended to show Baartman had been brought to Britain by persons who referred to her as if she were property. The second, by the Secretary of the African Association, described the degrading conditions under which she was exhibited and also gave evidence of coercion. Baartman was then questioned before an attorney in Dutch, in which she was fluent, via interpreters. However the conditions of the interview were stacked against her, in part again because the court saw Hendrik Cesars as the boer exploiter, rather than seeing Alexander Dunlop as the organizer. They thus ensured that Cesars was not in the room when Baartman made her statement, but Dunlop was allowed to remain.

The publicity given by the court case increased Baartman's popularity as an exhibit. She later toured other parts of England and was exhibited at a fair in Limerick, Ireland in 1812. She also was exhibited at a fair at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. On 1 December 1811 Baartman was baptized at Manchester Cathedral and there is evidence that she was married on the same day.

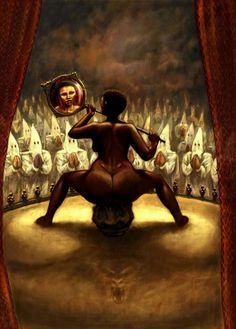

During 1814–70, there were at least seven scientific descriptions of the bodies of women of color done in comparative anatomy. Cuvier's dissection of Baartman helped shape European science. Baartman, along with several other African women who were dissected, were referred to as Hottentots, or sometimes Bushwomen. The "savage woman" was seen as very distinct from the "civilised female" of Europe, thus nineteenth century Scientists were fascinated by "the Hottentot Venus". In the 1800s, people in London were able to pay two shillings apiece to gaze upon her body in wonder. Baartman was considered a freak of nature. For extra pay, one could even poke her with a stick or finger. Sara Baartman's organs, genitalia and buttocks were thought to be evidence of her sexual primitivism and intellectual equality with that of an orangutan.

Baartman died on 29 December 1815 at age 26, of an undetermined inflammatory ailment, possibly smallpox, while other sources suggest she contracted syphilis, or pneumonia. Cuvier conducted a dissection, but did not do an autopsy to inquire into the reasons for Baartman's death.

French Anatomist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville published notes on the dissection in 1816, which were republished by Georges Cuvier in the Memoires du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle in 1817. Cuvier, who had met Baartman, notes in his monograph that its subject was an intelligent woman with an excellent memory, particularly for faces. In addition to her native tongue, she spoke fluent Dutch, passable English, and a smattering of French. He describes her shoulders and back as "graceful", arms "slender", hands and feet as "charming" and "pretty". He adds she was adept at playing the jew's harp, could dance according to the traditions of her country, and had a lively personality. Despite this, Cuvier interpreted her remains, in accordance with his theories on racial evolution, as evidencing ape-like traits. He thought her small ears were similar to those of an orangutan and also compared her vivacity, when alive, to the quickness of a monkey.

According to Writer Geneva S. Thomas, anyone that is aware of black women's history under colonialist influence would consequentially be aware that Kardashian's photo easily elicits memory regarding the visual representation of Baartman. The Photographer and Director of the photo, Jean-Paul Goude, based the photo on his previous work "Carolina Beaumont", taken of a nude model in 1976 and published in his book Jungle Fever.

A People Magazine article in 1979 about his relationship with model Grace Jones describes Goude in the following statement:

Baartman became an icon in South Africa as representative of many aspects of the nation's history. The Saartjie Baartman Centre for Women and Children, a refuge for survivors of domestic violence, opened in Cape Town in 1999. South Africa's first offshore environmental protection vessel, the Sarah Baartman, is also named after her.

Lyle Ashton Harris and Renee Valerie Cox worked in collaboration to produce the photographic piece Hottentot Venus 2000. In this piece, Harris photographs Victoria Cox who presents herself as Baartman while wearing large, sculptural, gold, metal breasts and buttocks attached to her body. According to Deborah Willis, the paraphernalia attached to Cox's body are markers for the way in which Baartman's sexual body parts were essential for her constructed role or function as the 'Hottentot Venus.' Willis also explains that Cox's side angle shot makes reference to the 'scientific' traditional propaganda used by Cuvier and Julian-Joseph Virey who sourced Baartman's traditional illustrations and iconography to publish their 'scientific' findings.

From the 1940s, there were sporadic calls for the return of her remains. A poem written in 1978 by Diana Ferrus, herself of Khoisan descent, entitled "I've come to take you home", played a pivotal role in spurring the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to her birth soil. The case gained world-wide prominence only after Stephen Jay Gould wrote The Mismeasure of Man in the 1980s. Mansell Upham, a researcher and jurist specializing in South African colonial history also helped spur the movement to bring Baartman's remains back to South Africa. After the victory of the African National Congress in the South African general election, 1994, President Nelson Mandela formally requested that France return the remains. After much legal wrangling and debates in the French National Assembly, France acceded to the request on 6 March 2002. Her remains were repatriated to her homeland, the Gamtoos Valley, on 6 May 2002 and they were buried on 9 August 2002 on Vergaderingskop, a hill in the town of Hankey over 200 years after her birth.

In response to the November 2014 photograph of Kim Kardashian, Cleuci de Oliveira published an article on Jezebel titled Saartjie Baartman: The Original Bootie Queen. Oliveira claims Sarah Baartman was "always an agent in her own path." She goes on to assert Baartman performed on her own terms and was unwilling to view herself as a tool for scientific advancement, an object of entertainment, or a pawn of the state.

Frieze.com published an article "‘Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Women Artists’, curated by Cameroonian-born Koyo Kouoh" which mentions Baartmans legacy and its impact on young female African artists. The work linked to Baartman is meant to reference the ethnographic exhibits of the nineteenth century that enslaved Baartman and displayed her naked body. Artist Oka's (Untitled, 2015) rendered a live performance of a black naked woman in a cage with the door swung open, walking around a sculpture of male genitalia, repeatedly. Her work was so impactful it led one audience member to proclaim, "Do we allow this to happen because we are in the white cube, or are we revolted by it?". [2] Oka's work has been described as 'black feminist art' where the female body is a site for activism and expression. The article also mentions other African female icons and how artists are expressing themselves through performance and discussion by posing the question "How Does the White Man Represent the Black Woman".

After Baartman's death, Geoffroy Saint Hilaire applied on behalf of the Muséum d' Histoire Naturelle to retain her corpse on the grounds that it was of singular specimen of humanity and therefore of special scientific interest. The application was approved and Baartman's skeleton and body cast were displayed in Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers, where she entertained visitors until her skull was stolen in 1827, and subsequently returned a few months later. The restored skeleton and skull continued to arouse the interest of visitors until the remains were moved to the Musée de l'Homme, when it was founded in 1937, and continued up until the late 1970s. Her body cast and skeleton stood side by side and faced away from the viewer which emphasized her steatopygia (accumulation of fat on the buttocks) while reinforcing that aspect as the primary interest of her body. The Baartman exhibit proved popular until it elicited complaints from feminists who believed the exhibit was a degrading representation of women. The skeleton was removed in 1974, and the body cast in 1976.