Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Nobel Prize Winner in Literature |

| Birth Day | February 07, 1885 |

| Birth Place | Sauk Centre, United States |

| Age | 134 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | January 10, 1951(1951-01-10) (aged 65)\nRome, Italy |

| Birth Sign | Pisces |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, short story writer |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1930 |

| Spouse | Grace Livingston Hegger (1914–1925) (divorced) Dorothy Thompson (1928–1942) (divorced) |

| Children | Two |

Net worth: $20 Million (2024)

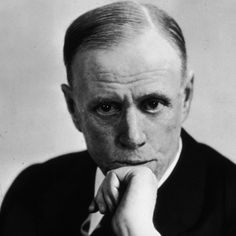

Sinclair Lewis, an acclaimed American author, is recognized for his literary contributions and unique storytelling style. Notably, his net worth is projected to reach an impressive $20 million by 2024. Lewis gained immense recognition for his exceptional talent and received the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature. This esteemed award further solidified his place in literary history, highlighting his profound impact on American literature. Sinclair Lewis remains a celebrated figure, with his works continuing to captivate readers worldwide.

Famous Quotes:

It has become rather commonplace for so-called literary critics to write off Sinclair Lewis as a novelist. Compared to ... Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Dos Passos, and Faulkner ... Lewis lacked style. Yet his impact on modern American life ... was greater than all of the other four writers together.

Biography/Timeline

Born February 7, 1885, in the village of Sauk Centre, Minnesota, Sinclair Lewis began reading books at a young age and kept a diary. He had two siblings, Fred (born 1875) and Claude (born 1878). His father, Edwin J. Lewis, was a physician and a stern disciplinarian who had difficulty relating to his sensitive, unathletic third son. Lewis's mother, Emma Kermott Lewis, died in 1891. The following year, Edwin Lewis married Isabel Warner, whose company young Lewis apparently enjoyed. Throughout his lonely boyhood, the ungainly Lewis—tall, extremely thin, stricken with acne and somewhat pop-eyed—had trouble gaining friends and pined after various local girls. At the age of 13 he unsuccessfully ran away from home, wanting to become a Drummer boy in the Spanish–American War. In late 1902 Lewis left home for a year at Oberlin Academy (the then-preparatory department of Oberlin College) to qualify for acceptance by Yale University. While at Oberlin, he developed a religious enthusiasm that waxed and waned for much of his remaining teenage years. He entered Yale in 1903 but did not receive his bachelor's degree until 1908, having taken time off to work at Helicon Home Colony, Upton Sinclair's cooperative-living colony in Englewood, New Jersey, and to travel to Panama. Lewis's unprepossessing looks, "fresh" country manners and seemingly self-important loquacity made it difficult for him to win and keep friends at Oberlin and Yale. He did initiate a few relatively long-lived friendships among students and professors, some of whom recognized his promise as a Writer.

Samuel J. Rogal edited The Short Stories of Sinclair Lewis (1904–1949), a seven-volume set published in 2007 by Edwin Mellen Press. The first attempt to collect all of Lewis's short stories.

Lewis's first published book was Hike and the Aeroplane, a Tom Swift-style potboiler that appeared in 1912 under the pseudonym Tom Graham.

In 1914 Lewis married Grace Livingston Hegger (1887–1981), an Editor at Vogue magazine. They had one son, Wells Lewis (1917–1944), named after British author H. G. Wells. Serving as a U.S. Army lieutenant during World War II, Wells Lewis was killed in action on October 29 amid Allied efforts to rescue the "Lost Battalion" in France. Dean Acheson, the Future Secretary of State, was a neighbor and family friend in Washington, and observed that Sinclair's literary "success was not good for that marriage, or for either of the parties to it, or for Lewis's work" and the family moved out of town.

During the late 1920s and 1930s, Lewis wrote many short stories for a variety of magazines and publications. "Little Bear Bongo" (1930) is a tale about a bear cub who wants to escape the circus in search of a better life in the real world, first published in Cosmopolitan magazine. The story was acquired by Walt Disney Pictures in 1940 for a possible feature film. World War II sidetracked those plans until 1947. Disney used the story (now titled "Bongo") as part of its feature Fun and Fancy Free.

Next Lewis published Elmer Gantry (1927), which depicted an evangelical minister as deeply hypocritical. The novel was denounced by many religious Leaders and banned in some U.S. cities. It was adapted for the screen more than a generation later as the basis of the 1960 movie starring Burt Lancaster, who earned a Best Actor Oscar for his performance.

Lewis divorced Grace in 1925. On May 14, 1928, he married Dorothy Thompson, a political newspaper columnist. Later in 1928, he and Dorothy purchased a second home in rural Vermont. They had a son, Michael Lewis, in 1930. Their marriage had virtually ended by 1937, and they divorced in 1942. Michael Lewis became an actor, who suffered with alcoholism, and died in 1975 of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Michael had two sons, John Paul and Gregory Claude, with wife Bernadette Nanse, and a daughter, Lesley, with wife Valerie Cardew.

Lewis next published Dodsworth (1929), a novel about the most affluent and successful members of American society. He portrayed them as leading essentially pointless lives in spite of great wealth and advantages. The book was adapted for the Broadway stage in 1934 by Sidney Howard, who also wrote the screenplay for the 1936 film version directed by william Wyler, which was a great success at the time. The film is still highly regarded; in 1990, it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry, and in 2005 Time magazine named it one of the "100 Best Movies" of the past 80 years.

After praising Dreiser as "pioneering," that he "more than any other man, marching alone, usually unappreciated, often hated, has cleared the trail from Victorian and Howellsian timidity and gentility in American fiction to honesty and boldness and passion of life" in his Nobel Lecture in December 1930, in March 1931 Lewis publicly accused Dreiser of plagiarizing a book by Dorothy Thompson, Lewis's wife, which led to a well-publicized fight, wherein Dreiser repeatedly slapped Lewis. Thompson initially made the accusation in 1928 regarding her work "The New Russia" and Dreiser's "Dreiser Goes to Russia", though the New York Times also linked the dispute to competition between Dreiser and Lewis over the Nobel Prize. Dreiser fired back that Sinclair's 1928 novel Arrowsmith (adapted later that year as a feature film) was unoriginal and that Dreiser himself was first approached to write it, which was disputed by the wife of Arrowsmith's subject, microbiologist Dr. Paul de Kruif. The feud carried on for some months. In 1944, however, Lewis campaigned to have Dreiser recognized by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Lewis wrote eleven more novels, ten of which appeared in his lifetime. The best remembered is It Can't Happen Here (1935), a novel about the election of a fascist to the American presidency.

After an alcoholic binge in 1937, Lewis checked in for treatment to the Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric hospital in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. His doctors gave him a blunt assessment that he needed to decide "whether he was going to live without alcohol or die by it, one or the other." Lewis checked out after ten days, lacking any "fundamental understanding of his Problem," as one of his Physicians wrote to a colleague.

In the early 1940s, Lewis lived in Duluth, Minnesota. During this time, he wrote the novel Kingsblood Royal (1947), set in the fictional city of Grand Republic, Minnesota, an enlarged and updated version of Zenith. It is based on the Sweet Trials in Detroit in which an African-American Doctor was denied the chance to purchase a house in a "white" section of the city. Kingsblood Royal was a powerful and very early contribution to the civil rights movement.

In 1943, Lewis went to Hollywood to work on a script with Dore Schary, who had just resigned as executive head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's low-budget film department to concentrate on writing and producing his own films. The resulting screenplay was Storm In the West, "a traditional American western" — except for the fact that it was also an allegory of World War II, with primary villain Hygatt (Hitler) and his henchmen Gribbles (Goebbels) and Gerrett (Goering) plotting to take over the Franson Ranch, the Poling Ranch, and so on. The screenplay was deemed too political by MGM studio executives and was shelved, and the film was never made. Storm In the West was finally published in 1963, with a foreword by Schary detailing the work's origins, the authors' creative process, and the screenplay's ultimate fate.

Sinclair Lewis had been a frequent visitor to Williamstown, Massachusetts. In 1946, he rented Thorvale Farm on Oblong Road. While working on his novel Kingsblood Royal, he purchased this summer estate and upgraded the Georgian mansion along with a farmhouse and many outbuildings. By 1948, Lewis had created a gentleman’s farm consisting of 720 acres of agricultural and forest land. His intended residence in Williamstown was short-lived because of his medical problems.

Lewis died in Rome from advanced alcoholism on January 10, 1951, aged 65. His body was cremated and his remains were buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Sauk Centre, Minnesota. His final novel World So Wide (1951) was published posthumously.

Lewis's earliest published creative work—romantic poetry and short sketches—appeared in the Yale Courant and the Yale Literary Magazine, of which he became an Editor. After graduation Lewis moved from job to job and from place to place in an effort to make ends meet, write fiction for publication and to chase away boredom. While working for newspapers and publishing houses (and for a time at the Carmel-by-the-Sea, California writers' colony), he developed a facility for turning out shallow, popular stories that were purchased by a variety of magazines. He also earned money by selling plots to Jack London, including one for the latter's unfinished novel The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.