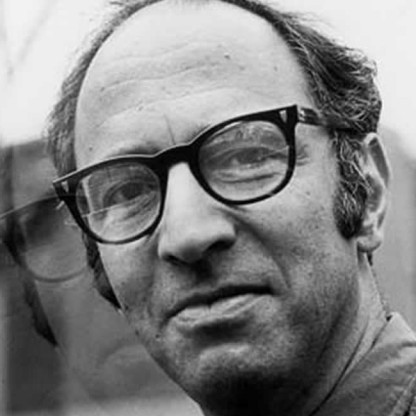

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Physicist |

| Birth Day | July 18, 1922 |

| Birth Place | Cincinnati, United States |

| Age | 98 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | June 17, 1996(1996-06-17) (aged 73)\nCambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Leo |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic Historical turn |

| Main interests | Philosophy of science |

| Notable ideas | Paradigm shift Incommensurability Normal science Kuhn loss |

Net worth: $4 Million (2024)

Thomas Kuhn, a renowned physicist in the United States, is projected to have a net worth of $4 million by 2024. With his significant contributions to the field of physics, Kuhn has not only established a strong reputation but also amassed considerable wealth. Known for his groundbreaking research and theoretical advancements, Kuhn's expertise has undoubtedly propelled him to financial success. His net worth is a testament to his exceptional career and the recognition he has garnered within the scientific community.

Biography/Timeline

Kuhn was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Samuel L. Kuhn, an industrial Engineer, and Minette Stroock Kuhn, both Jewish. He graduated from The Taft School in Watertown, CT, in 1940, where he became aware of his serious interest in mathematics and physics. He obtained his BS degree in physics from Harvard University in 1943, where he also obtained MS and PhD degrees in physics in 1946 and 1949, respectively, under the supervision of John Van Vleck. As he states in the first few pages of the preface to the second edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, his three years of total academic freedom as a Harvard Junior Fellow were crucial in allowing him to switch from physics to the history and philosophy of science. He later taught a course in the history of science at Harvard from 1948 until 1956, at the suggestion of university President James Conant. After leaving Harvard, Kuhn taught at the University of California, Berkeley, in both the philosophy department and the history department, being named Professor of the History of science in 1961. Kuhn interviewed and tape recorded Danish Physicist Niels Bohr the day before Bohr's death. At Berkeley, he wrote and published (in 1962) his best known and most influential work: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In 1964, he joined Princeton University as the M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Philosophy and History of Science. He served as the President of the History of Science Society from 1969–70. In 1979 he joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy, remaining there until 1991. In 1994 Kuhn was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died in 1996.

Kuhn was named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1954, and in 1982 was awarded the George Sarton Medal by the History of Science Society. He also received numerous honorary doctorates.

In SSR, Kuhn also argues that rival paradigms are incommensurable—that is, it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and terminology of another rival paradigm. For many critics, for Example David Stove (Popper and After, 1982), this thesis seemed to entail that theory choice is fundamentally irrational: if rival theories cannot be directly compared, then one cannot make a rational choice as to which one is better. Whether Kuhn's views had such relativistic consequences is the subject of much debate; Kuhn himself denied the accusation of relativism in the third edition of SSR, and sought to clarify his views to avoid further misinterpretation. Freeman Dyson has quoted Kuhn as saying "I am not a Kuhnian!", referring to the relativism that some Philosophers have developed based on his work.

In regard to experimentation and collection of data with a view toward solving problems through the commitment to a paradigm, Kuhn states: “The operations and measurements that a scientist undertakes in the laboratory are not ‘the given’ of experience but rather ‘the collected with diffculty.’ They are not what the scientist sees—at least not before his research is well advanced and his attention focused. Rather, they are concrete indices to the content of more elementary perceptions, and as such they are selected for the close scrutiny of normal research only because they promise opportunity for the fruitful elaboration of an accepted paradigm. Far more clearly than the immediate experience from which they in part derive, operations and measurements are paradigm-determined. Science does not deal in all possible laboratory manipulations. Instead, it selects those relevant to the juxtaposition of a paradigm with the immediate experience that that paradigm has partially determined. As a result, Scientists with different paradigms engage in different concrete laboratory manipulations.”