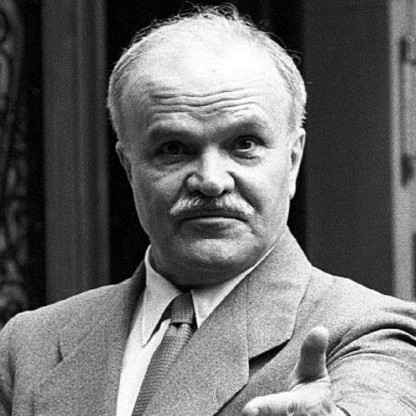

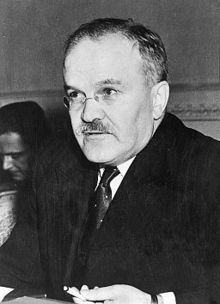

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Politician |

| Birth Day | March 09, 1890 |

| Birth Place | Sovetsk, Russia, Russian |

| Age | 129 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 8 November 1986(1986-11-08) (aged 96)\nMoscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Birth Sign | Aries |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Krestinsky |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Stalin (as general secretary) |

| Premier | Georgy Malenkov Nikolai Bulganin |

| Citizenship | Soviet |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Spouse(s) | Polina Zhemchuzhina |

Net worth: $100,000 (2024)

Vyacheslav Molotov, a distinguished and influential politician in Russian history, is estimated to have a net worth of $100,000 in 2024. Molotov's political career flourished predominantly during the Soviet era, where he held prominent positions such as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars and Minister of Foreign Affairs. Often regarded as a close confidant of Joseph Stalin, he played a significant role in shaping Soviet policies and international relations. Despite his significant contributions to the political landscape, Molotov's net worth remains relatively modest compared to contemporary politicians, reflecting a more austere lifestyle in line with Soviet ideals. His legacy, however, extends beyond financial accomplishments, as he is remembered for his political acumen and defining era-defining decisions.

Biography/Timeline

Molotov was born Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in the village of Kukarka, Yaransk Uyezd, Vyatka Governorate (now Sovetsk in Kirov Oblast), the son of a butter churner. Contrary to a commonly repeated error, he was not related to the Composer Alexander Scriabin. Throughout his teen years, he was described as "shy" and "quiet", always assisting his father with his Business. He was educated at a secondary school in Kazan, and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1906, soon gravitating toward that organisation's radical Bolshevik faction, headed by V. I. Lenin.

Skryabin took the pseudonym "Molotov", derived from the Russian word молот molot (hammer) for his political work owing to the name's vaguely "industrial" ring. He was arrested in 1909 and spent two years in exile in Vologda. In 1911, he enrolled at St Petersburg Polytechnic. Molotov joined the editorial staff of a new underground Bolshevik newspaper called Pravda, meeting Joseph Stalin for the first time in association with the project. This first association between the two Future Soviet Leaders proved to be brief, however, and did not lead to an immediate close political association.

Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, writing for the party press and attempting to better organize the underground party. He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the time of the outbreak of World War I. It was in Moscow the following year that Molotov was again arrested for his party activity, this time being deported to Irkutsk in eastern Siberia. In 1916 he escaped from his Siberian exile and returned to the capital city, now called Petrograd by the Tsarist regime, which thought the name St. Petersburg sounded excessively German.

Molotov became a member of the Bolshevik Party's committee in Petrograd in 1916. When the February Revolution occurred in 1917, he was one of the few Bolsheviks of any standing in the capital. Under his direction Pravda took to the "left" to oppose the Provisional Government formed after the revolution. When Joseph Stalin returned to the capital, he reversed Molotov's line; but when the party leader Lenin arrived, he overruled Stalin. Despite this, Molotov became a protégé of and close adherent to Stalin, an alliance to which he owed his later prominence. Molotov became a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee which planned the October Revolution, which effectively brought the Bolsheviks to power.

In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the civil war then breaking out. Since he was not a military man, he took no part in the fighting. In 1920, he became secretary to the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Bolshevik Party. Lenin recalled him to Moscow in 1921, elevating him to full membership of the Central Committee and Orgburo, and putting him in charge of the party secretariat. He was voted in as a non-voting member of the Politburo in 1921 and held the office of Responsible Secretary and also married Soviet Politician Polina Zhemchuzhina.

His Responsible Secretaryship was criticised by Lenin and Leon Trotsky, with Lenin noting his "shameful bureaucratism" and stupid behaviour. On the advice of Molotov and Nikolai Bukharin, the Central Committee decided to reduce Lenin's work hours. In 1922, Stalin became general secretary of the Bolshevik Party with Molotov as the de facto Second Secretary. As a young follower, Molotov admired Stalin but was open in criticism of him. Under Stalin's patronage, Molotov became a member of the Politburo in 1926.

During the power struggles which followed Lenin's death in 1924, Molotov remained a loyal supporter of Stalin against his various rivals: first Leon Trotsky, later Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev and finally Nikolai Bukharin. Molotov became a leading figure in the "Stalinist centre" of the party, which also included Kliment Voroshilov and Sergo Ordzhonikidze. Trotsky and his supporters underestimated Molotov, as did many others. Trotsky called him "mediocrity personified", whilst Molotov himself pedantically corrected comrades referring to him as 'Stone Arse' by saying that Lenin had actually dubbed him 'Iron Arse'.

However, this outward dullness concealed a sharp mind and great administrative talent. He operated mainly behind the scenes and cultivated an image of a colourless bureaucrat – for Example, he was the only Bolshevik leader who always wore a suit and tie. In 1928, Molotov replaced Nikolai Uglanov as First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party and held that position until 15 August 1929. In a lengthy address to the Central Committee in 1929, Molotov told the members the Soviet government would initiate a compulsory collectivisation campaign to solve the agrarian backwardness of Soviet agriculture.

During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Alexey Rykov, the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (the equivalent of a Western head of government) was succeeded by Molotov. In this post, Molotov oversaw the Stalin regime's collectivisation of agriculture. He followed Stalin's line by using a combination of force and propaganda to crush peasant resistance to collectivisation, including the deportation of millions of kulaks (peasants with property) to gulags. An enormous number of the deportees died from exposure and overwork. He signed the Law of Spikelets and personally led the Extraordinary Commission for Grain Delivery in Ukraine, which seized a reported 4.2 million tonnes of grain from the peasants during a widespread manmade famine (later known as the "Holodomor" to Ukrainians). Contemporary historians estimate that between seven and eleven million people died, either of starvation or in gulags, in the process of farm collectivization. Molotov also oversaw the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan for rapid industrialisation.

Sergei Kirov, head of the Party organisation in Leningrad, was killed in 1934; some believed Stalin ordered his death. Kirov's death triggered a second crisis, the Great Purge. In 1938, out of the 28 People's Commissars in Molotov's Government, 20 were executed on the orders of Molotov and Stalin. The purges were carried out by Stalin's successive police chiefs, Nikolai Yezhov was the chief organiser and Kliment Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich and Molotov were intimately involved in the processes. Stalin frequently required Molotov and other Politburo members to sign the death warrants of prominent purge victims, and Molotov always did so without question.

Molotov was reported to be a vegetarian and teetotaler by American Journalist John Gunther in 1938. However, Milovan Djilas claimed that Molotov "drank more than Stalin" and did not note his vegetarianism despite attending several banquets with him.

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler authorised Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to begin serious negotiations. A trade agreement was concluded on 18 August; and on 22 August, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to conclude a formal non-aggression treaty. Although the treaty is known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, it was Stalin and Hitler, and not Molotov and Ribbentrop, who decided the content of the treaty.

In November 1940, Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to meet Ribbentrop and Adolf Hitler. In January 1941, the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden visited Turkey in an attempt to get the Turks to enter the war on the Allies' side. Though the purpose of Eden's visit was anti-German rather than anti-Soviet, Molotov assumed otherwise, and in a series of conversations with the Italian Ambassador Augusto Rosso, Molotov claimed that the Soviet Union would soon be faced with an Anglo-Turkish invasion of the Crimea. The British Historian D.C. Watt argued that on the basis of Molotov's statements to Rosso, it would appear that in early 1941, Stalin and Molotov viewed Britain rather than Germany as the principal threat.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet-German relations until June 1941 when Hitler, having occupied France and neutralised Britain, turned east and attacked the Soviet Union. Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack, when he instead of Stalin announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated for Britain by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches. The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech; Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.

After signing the Anglo-Soviet Treaty of 1942 on 26 May Molotov left for Washington, D.C., United States. Molotov met with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President of the United States, and ratified a Lend-Lease Treaty between the USSR and the US. Both the British and the United States government, albeit vaguely, promised to open up a second front against Germany. On his FLIGHT back to the USSR his plane was attacked by German fighters, and then later by Soviet fighters.

In a collaboration with Kliment Voroshilov, Molotov contributed both musically and lyrically to the 1944 version of the Soviet national anthem. Molotov asked the Writers to include a line or two about peace. Molotov's and Voroshilov's role in the making of the new Soviet anthem was, in the words of Historian Simon Sebag-Montefiore, acting as music judges for Stalin.

From 1945 to 1947, Molotov took part in all four conferences of foreign ministers of the victorious states in World War II. In general, he was distinguished by an uncooperative attitude towards the Western powers. Molotov, at the direction of the Soviet government, condemned the Marshall Plan as imperialistic and claimed it was dividing Europe into two camps, one capitalist and the other communist. In response, the Soviet Union, along with the other Eastern Bloc nations, initiated what is known as the Molotov Plan. The plan created several bilateral relations between the states of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union; and later evolved into the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA).

Molotov accompanied Stalin to the Teheran Conference in 1943, the Yalta Conference in 1945 and, following the defeat of Germany, the Potsdam Conference. He represented the Soviet Union at the San Francisco Conference, which created the United Nations. Even during the period of wartime alliance, Molotov was known as a tough negotiator and a determined defender of Soviet interests. Molotov lost his position of First Deputy Chairman on March 19, 1946, after the Council of People's Commissars was reformed as the Council of Ministers.

Polina Zhemchuzhina befriended Golda Meir, who arrived in Moscow in November 1948 as the first Israeli envoy to the USSR. According to a close collaborator of Molotov, Vladimir Erofeev, Golda Meir met privately with Polina, who had been her schoolmate in St. Petersburg. Immediately afterwards, Polina was arrested and accused of ties with Zionist organisations; she was kept one year in the Lubyanka, after which she was exiled for three years in an obscure Russian city. Molotov had no communication with her, save for the scant news that Beria, whom he loathed, told him. She was freed immediately after the death of Stalin. According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in Soviet Union; she's also a real Bolshevik, a real Soviet person." In 1949, Molotov was replaced as Foreign Minister by Andrey Vyshinsky, although retaining his position as First Deputy Premier and membership of the Politburo.

After World War II (Great Patriotic War), Molotov was involved in negotiations with the Western allies, in which he became noted for his diplomatic skills. He retained his place as a leading Soviet diplomat and Politician until March 1949, when he fell out of Stalin's favour and lost the foreign affairs ministry leadership to Andrei Vyshinsky. Molotov's relationship with Stalin deteriorated further, with Stalin criticising Molotov in a speech to the 19th Party Congress. However, after Stalin's death in 1953, Molotov was staunchly opposed to Khrushchev's de-Stalinisation policy. Molotov defended Stalin's policies and legacy until his death in 1986, and harshly criticised Stalin's successors, especially Khrushchev.

At the 19th Party Congress in 1952, Molotov was elected to the replacement for the Politburo, the Presidium, but was not listed among the members of the newly established secret body known as the Bureau of the Presidium; indicating that he had fallen out of Stalin's favour. At the 19th Congress, Molotov and Anastas Mikoyan were said by Stalin to have committed grave mistakes, including the publication of a wartime speech by Winston Churchill favourable to the Soviet Union's wartime efforts. Both Molotov and Mikoyan were falling out of favour rapidly, with Stalin telling Beria, Khrushchev, Malenkov and Nikolai Bulganin that he did not want to see Molotov and Mikoyan around anymore. At his 73rd birthday, Stalin treated both with disgust. In his speech to the 20th Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev told delegates that Stalin had had plans for "finishing off" Molotov and Mikoyan in the aftermath of the 19th Congress.

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position. Georgy Malenkov, Stalin's successor in the post of Premier, reappointed Molotov as Minister of Foreign Affairs on 5 March 1953. Although Molotov was seen as a likely successor to Stalin in the immediate aftermath of his death, he never sought to become leader of the Soviet Union. A Troika was established immediately after Stalin's death, consisting of Malenkov, Beria, and Molotov, but ended when Malenkov and Molotov deceived Beria. Molotov supported the removal and later the execution of Beria on the orders of Khrushchev. The new Party Secretary, Khrushchev, soon emerged as the new leader of the Soviet Union. He presided over a gradual domestic liberalisation and a thaw in foreign policy, as was manifest in a reconciliation with Josip Broz Tito's government in Yugoslavia, which Stalin had expelled from the communist movement. Molotov, an old-guard Stalinist, seemed increasingly out of place in the new environment, but he represented the Soviet Union at the Geneva Conference of 1955.

Molotov's position became increasingly tenuous after February 1956, when Khrushchev launched an unexpected denunciation of Stalin at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party. Khrushchev attacked Stalin both over the purges of the 1930s and the defeats of the early years of World War II, which he blamed on Stalin's overly trusting attitude towards Hitler and his purges of the Red Army command structure. As Molotov was the most senior of Stalin's collaborators still in government and had played a leading role in the purges, it became evident that Khrushchev's examination of the past would probably result in Molotov's fall from power, and he became the leader of an old guard faction that sought to overthrow Khrushchev.

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister; on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium, 7–4, to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so. In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated. Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic. Molotov and his associates were denounced as "the Anti-Party Group" but, notably, were not subject to such unpleasant repercussions as had been customary for denounced officials in the Stalin years. In 1960, he was appointed Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency, which was seen as a partial rehabilitation. However, after the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, during which Khrushchev carried out his de-Stalinisation campaign, including the removal of Stalin's body from Lenin's Mausoleum, Molotov (along with Lazar Kaganovich) was removed from all positions and expelled from the Communist Party. In 1962, all of Molotov's party documents and files were destroyed by the authorities.

In retirement, Molotov remained unrepentant about his role under Stalin's rule. He suffered a heart attack in January 1962. After the Sino-Soviet split, it was reported that he agreed with the criticisms made by Mao Zedong of the supposed "revisionism" of Khrushchev's policies. According to Roy Medvedev, Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva recalled Molotov's wife telling her: "Your father was a genius. There's no revolutionary spirit around nowadays, just opportunism everywhere" and "China's our only hope. Only they have kept alive the revolutionary spirit".

The first signs of a rehabilitation were seen during Leonid Brezhnev's rule, when information about him was again allowed to be included in Soviet encyclopaedias. His connection, support and work in the Anti-Party Group was mentioned in encyclopedias published in 1973 and 1974, but eventually disappeared altogether by the mid-to-late-1970s. Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko further rehabilitated Molotov; in 1984 Molotov was even allowed to seek membership in the Communist Party. A collection of interviews with Molotov from 1985 was published in 1994 by Felix Chuev as Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics. In June 1986, Molotov was hospitalized in Kuntsevo hospital in Moscow and he died, during the rule of Mikhail Gorbachev, on 8 November 1986. During his long life Molotov suffered seven myocardial infarctions, but lived to 96 years and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow.

At the end of 1989, two years before the final collapse of the Soviet Union, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union and Mikhail Gorbachev's government formally denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, acknowledging that the bloody annexation of the Baltic States and the partition of Poland had been illegal.

Molotov was the principal Soviet signatory of the Nazi–Soviet non-aggression pact of 1939 (also known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact), whose most important provisions were added in the form of a secret protocol that stipulated an invasion of Poland and partition of its territory between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. He was aware of the Katyn massacre committed by the Soviet authorities during this period.