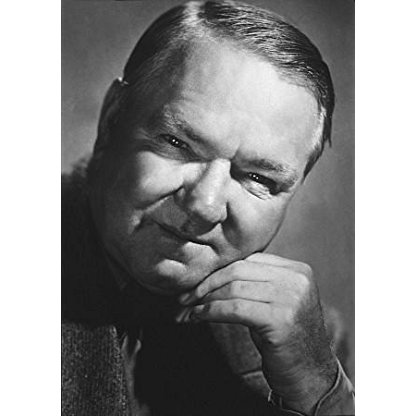

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | Actor, Writer, Soundtrack |

| Birth Day | January 29, 1880 |

| Birth Place | Darby, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Age | 139 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | December 25, 1946(1946-12-25) (aged 66)\nPasadena, California, U.S. |

| Birth Sign | Aquarius |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California |

| Other names | Charles Bogle Otis Criblecoblis Mahatma Kane Jeeves |

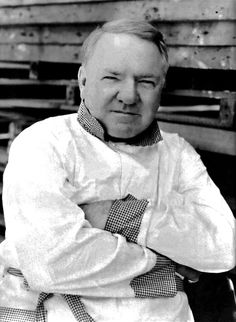

| Occupation | Actor, comedian, juggler, writer |

| Years active | 1898–1946 |

| Spouse(s) | Harriet Hughes (m. 1900–1946) (his death) 1 child |

| Partner(s) | Bessie Poole (girlfriend) 1 child Carlotta Monti (girlfriend) |

| Children | William Claude Fields Jr. William Morris |

Net worth

W.C. Fields, a renowned actor, writer, and soundtrack artist hailing from the United States, is anticipated to have a net worth ranging between $100,000 and $1 million in the year 2024. Fields, with his wit, comedic timing, and distinct personality, became a prominent figure in the entertainment industry during his time. His contributions to the world of cinema and his multifaceted career have undoubtedly played a significant role in accumulating his considerable wealth.

Famous Quotes:

One day the producers appeared on the set to plead with Fields: "Please don't drink while we're shooting—we're way behind schedule" ... Fields merely raised an eyebrow. "Gentlemen, this is only lemonade. For a little acid condition afflicting me." He leaned on me. "Would you be kind enough to taste this, sir?" I took a careful sip—pure gin. I have always been a friend of the drinking man; I respect him for his courage to withdraw from the world of the thinking man. I answered the producers a little scornfully, "It's lemonade." My reward? The scene was snipped out of the picture.

Biography/Timeline

Fields was born william Claude Dukenfield in Darby, Pennsylvania, the oldest child of a working-class family. His father, James Lydon Dukenfield (1840–1913), was from an English family that emigrated from Sheffield, England in 1854. James Dukenfield served in Company M of the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment in the American Civil War and was wounded in 1863. Fields' mother, Kate Spangler Felton (1854–1925), was a Protestant of British ancestry. The 1876 Philadelphia City Directory lists James Dukenfield as a clerk. After marrying, he worked as an independent produce merchant and a part-time hotel-keeper.

Claude Dukenfield (as he was known) had a volatile relationship with his short-tempered father. He ran away from home repeatedly, beginning at the age of nine, often to stay with his grandmother or an uncle. His education was sporadic, and did not progress beyond grade school. At age twelve, he worked with his father selling produce from a wagon, until the two had a fight that resulted in Fields running away once again. In 1893, he worked briefly at the Strawbridge and Clothier department store, and in an oyster house.

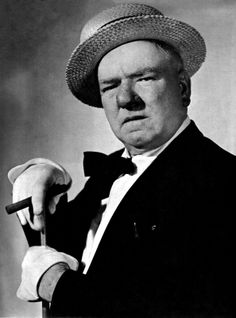

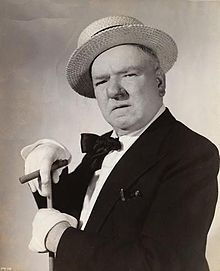

Inspired by the success of the "Original Tramp Juggler", James Edward Harrigan, Fields adopted a similar costume of scruffy beard and shabby tuxedo and entered vaudeville as a genteel "tramp juggler" in 1898, using the name W. C. Fields. His family supported his ambitions for the stage and saw him off on the train for his first stage tour. To conceal a stutter, Fields did not speak onstage. In 1900, seeking to distinguish himself from the many "tramp" acts in vaudeville, he changed his costume and makeup, and began touring as "The Eccentric Juggler". He manipulated cigar boxes, hats, and other objects in what appears to have been a unique and fresh act, parts of which are reproduced in some of his films, notably in The Old Fashioned Way (1934).

Fields married a fellow vaudevillian, chorus girl Harriet "Hattie" Hughes (1879–1963), on April 8, 1900. She became part of Fields' stage act, appearing as his assistant, whom he would entertainingly blame whenever he missed a trick. Hattie was well educated and tutored Fields in reading and writing during their travels. Fields became an enthusiastic reader and habitually traveled with a trunkful of books that included grammar books, translations of Homer and Ovid, and works by authors ranging from Shakespeare to Dickens to Twain.

The couple had a son, william Claude Fields, Jr. (July 28, 1904 – February 16, 1971) and although Fields was an avowed atheist—who, according to James Curtis, "regarded all religions with the suspicion of a seasoned con man"—he yielded to Hattie's wish to have their son baptized.

In 1905 Fields made his Broadway debut in a musical comedy, The Ham Tree. His role in the show required him to deliver lines of dialogue, which he had never before done onstage. He later said, "I wanted to become a real Comedian, and there I was, ticketed and pigeonholed as merely a comedy juggler." In 1913 he performed on a bill with Sarah Bernhardt (who regarded Fields as "an artiste [who] could not fail to please the best class of audience") first at the New York Palace, and then in England in a royal performance for the king and queen. He continued touring in vaudeville until 1915.

Fields met Carlotta Monti (1907–1993) in 1933, and the two began a sporadic relationship that lasted until his death in 1946. Monti had small roles in two of Fields' films, and in 1971 wrote a memoir, W.C. Fields and Me, which was made into a motion picture at Universal Studios in 1976. Fields was listed in the 1940 census as single and living at 2015 DeMille Drive (Cecil B. DeMille lived at 2000, the only other address on the street).

In 1915, Fields starred in two short comedies, Pool Sharks and His Lordship's Dilemma, filmed in New York. His stage commitments prevented him from doing more movie work until 1924, when he played a supporting role in Janice Meredith, a Revolutionary War romance. He reprised his Poppy role in a silent-film adaptation, retitled Sally of the Sawdust (1925) and directed by D. W. Griffith. His next starring role was in the Paramount Pictures film It's the Old Army Game (1926), which featured his friend Louise Brooks, later a screen legend for her role in G. W. Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) in Germany. Fields' 1926 film, which included a silent version of the porch sequence that would later be expanded in the sound film It's a Gift (1934), had only middling success at the box office. After Fields' next two features for Paramount failed to produce hits, the studio teamed him with Chester Conklin for three features which were commercial failures and are now lost.

While performing in New York City at the New Amsterdam Theater in 1916, Fields met Bessie Poole, an established Ziegfeld Follies performer whose beauty and quick wit attracted him, and they began a relationship. With her he had another son, named william Rexford Fields Morris (August 15, 1917 – November 30, 2014). Neither Fields nor Poole wanted to abandon touring to raise the child, who was placed in foster care with a childless couple of Bessie's acquaintance. Fields' relationship with Poole lasted until 1926. In 1927, he made a negotiated payment to her of $20,000 upon her signing an affidavit declaring that "W. C. Fields is NOT the father of my child". Poole died of complications of alcoholism in October 1928, and Fields contributed to her son's support until he was 19 years of age.

His career in show Business began in vaudeville, where he attained international success as a silent juggler. He gradually incorporated comedy into his act, and was a featured Comedian in the Ziegfeld Follies for several years. He became a star in the Broadway musical comedy Poppy (1923), in which he played a colorful small-time con man. His subsequent stage and film roles were often similar scoundrels, or else henpecked everyman characters.

Fields often contributed to the scripts of his films under unusual pseudonyms. They include the seemingly prosaic "Charles Bogle", credited in four of his films in the 1930s; "Otis Criblecoblis", which contains an embedded homophone for "scribble"; and "Mahatma Kane Jeeves", a play on Mahatma and a phrase an aristocrat might use when about to leave the house: "My hat, my cane, Jeeves".

In the sound era, Fields appeared in thirteen feature films for Paramount Pictures, beginning with Million Dollar Legs in 1932. In that year he also was featured in a sequence in the anthology film If I Had a Million. In 1932 and 1933, Fields made four short subjects for comedy pioneer Mack Sennett, distributed through Paramount Pictures. These shorts, adapted with few alterations from Fields' stage routines and written entirely by himself, were described by Simon Louvish as "the 'essence' of Fields". The first of them, The Dentist, is unusual in that Fields portrays an entirely unsympathetic character: he cheats at golf, assaults his caddy, and treats his patients with unbridled callousness. william K. Everson says that the cruelty of this comedy made it "hardly less funny", but that "Fields must have known that The Dentist presented a serious flaw for a comedy image that was intended to endure", and showed a somewhat warmer persona in his subsequent Sennett shorts.

Fields' screen character often expressed a fondness for alcohol, a prominent component of the Fields legend. Fields never drank in his early career as a juggler, because he did not want to impair his functions while performing. Eventually, the loneliness of constant travel prompted him to keep liquor in his dressing room as an inducement for fellow performers to socialize with him on the road. Only after he became a Follies star and abandoned juggling did Fields begin drinking regularly. His role in Paramount Pictures' International House (1933), as an aviator with an unquenchable taste for beer, did much to establish Fields' popular reputation as a prodigious drinker. Studio publicists promoted this image, as did Fields himself in press interviews.

His 1934 classic It's a Gift included his stage Sketch of trying to escape his nagging family by sleeping on the back porch and being bedeviled by noisy neighbors and salesmen. That film, like You're Telling Me! and Man on the Flying Trapeze, ended happily with a windfall profit that restored his standing in his screen families.

He achieved a career ambition by playing the character Mr. Micawber, in MGM's David Copperfield in 1935. In 1936, Fields re-created his signature stage role in Poppy for Paramount Pictures.

In 1936, Fields' heavy drinking precipitated a significant decline in his health. By the following year he recovered sufficiently to make one last film for Paramount, The Big Broadcast of 1938, but his troublesome behavior discouraged other producers from hiring him. By 1938 he was chronically ill, and suffering from delirium tremens.

In 1937, in an article in Motion Picture magazine, Fields analyzed the characters he played:

During his recovery from illness, Fields reconciled with his estranged wife and established a close relationship with his son after Claude's marriage in 1938.

W. C. Fields was (with Ed Wynn) one of the two original choices for the title role in the 1939 version of The Wizard of Oz. Fields was enthusiastic about the role, but ultimately withdrew his name from consideration so he could devote his time to writing You Can't Cheat an Honest Man.

Fields' film career slowed considerably in the 1940s. His illnesses confined him to brief guest-star appearances in other people's films. An extended sequence in 20th Century Fox's Tales of Manhattan (1942) was cut from the original release of the film and later reinstated for some home video releases. The scene features a temperance meeting with society people at the home of a rich woman, played by Margaret Dumont, in which Fields finds that the punch has been spiked, resulting in a room full of drunken guests and a very happy Fields.

Fields often fraternized at his home with actors, Directors, and Writers who shared his fondness for good company and good liquor. John Barrymore, Gene Fowler, and Gregory La Cava were a few of his intimates. On March 15, 1941, while Fields was out of town, Christopher Quinn, the two-year-old son of his neighbors, actor Anthony Quinn and his wife Katherine DeMille, drowned in a lily pond on Fields' property. Grief-stricken over the tragedy, he had the pond filled in.

On movie sets Fields famously shot most of his scenes in varying states of inebriation. During the filming of Tales of Manhattan (1942), he kept a vacuum flask with him at all times and frequently availed himself of its contents. Phil Silvers, who had a minor supporting role in the scene featuring Fields, described in his memoir what happened next:

However, from 1944 forward, Fields continued to make radio guest appearances, where script memorization was not necessary. One of the more notable guest shots was with a young Frank Sinatra on Sinatra's CBS radio program on February 9, 1944.

Field's final radio appearance was on March 24, 1946, on the Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy Show on NBC. Shortly before his death that year, Fields recorded a spoken-word album, including his "Temperance Lecture" and "The Day I Drank a Glass of Water", at Les Paul's studio, where Paul had installed his new multi-track recorder. The session was arranged by Paul's old Army pal Bill Morrow, one of Fields' radio Writers. It was Fields' last performance.

Fields spent the last 22 months of his life at the Las Encinas Sanatorium in Pasadena, California. In 1946, on Christmas Day—the holiday he said he despised—he suffered an alcohol-related gastric hemorrhage and died, at the age of 66. Carlotta Monti wrote that in his final moments, she used a garden hose to spray water onto the roof over his bedroom to simulate his favorite sound, falling rain. According to a 2004 documentary, he winked and smiled at a nurse, put a finger to his lips, and died. This poignant depiction is uncorroborated and "unlikely", according to biographer James Curtis. Fields' funeral took place on January 2, 1947, in Glendale, California.

Cremation of Fields' remains, as directed in his will, was delayed pending resolution of an objection filed by Hattie and Claude Fields on religious grounds. They also contested a clause leaving a portion of his estate to establish a "W. C. Fields College for Orphan White Boys and Girls, where no religion of any sort is to be preached". After a lengthy period of litigation his remains were cremated on June 2, 1949, and his ashes interred at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale.

The Surrealists loved Fields absurdism and anarchistic pranks. Max Ernst painted a Project for a Monument to W.C. Fields (1957), and René Magritte made a Hommage to Mack Sennett (1934).

Fields is one of the figures that appears in the crowd scene on the cover of The Beatles' 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

A best-selling biography of Fields published three years after his death, W.C. Fields, His Follies and Fortunes by Robert Lewis Taylor, was instrumental in popularizing the idea that Fields' real-life character matched his screen persona. In 1973, the comedian's grandson, Ronald J. Fields, published the first book to significantly challenge this idea, W. C. Fields by Himself, His Intended Autobiography, a compilation of material from private scrapbooks and letters found in the home of Hattie Fields after her death in 1963.

The United States Postal Service issued a W.C. Fields commemorative stamp on the comedian's 100th birthday, in January 1980.

In a 1994 episode of the Biography television series, Fields' 1941 co-star Gloria Jean recalled her conversations with Fields at his home. She described him as kind and gentle in personal interactions, and believed he yearned for the family environment he never experienced as a child.

According to Woody Allen (in a New York Times interview from January 30, 2000), W. C. Fields is one of six "genuine comic geniuses" he recognized as such in movie history, along with Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Groucho and Harpo Marx, and Peter Sellers.

Fields often reproduced elements of his own family life in his films. By the time he entered motion pictures, his relationship with his estranged wife had become acrimonious, and he believed she had turned their son Claude—whom he seldom saw—against him. James Curtis says of Man on the Flying Trapeze that the "disapproving mother-in-law, Mrs. Neselrode, was clearly patterned after his wife, Hattie, and the unemployable mama's boy played by [Grady] Sutton was deliberately named Claude. Fields hadn't laid eyes on his family in nearly twenty years, and yet the painful memories lingered."