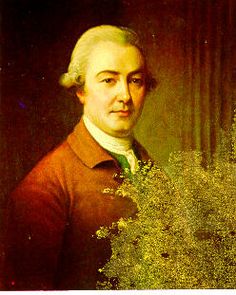

Age, Biography and Wiki

| Who is it? | The Great Commoner |

| Birth Day | November 15, 1708 |

| Birth Place | Westminster, British |

| Age | 311 YEARS OLD |

| Died On | 11 May 1778(1778-05-11) (aged 69)\nHayes, Kent, England |

| Birth Sign | Sagittarius |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Thomas Winnington |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Darlington The Earl of Kinnoull |

| Prime Minister | Henry Pelham The Duke of Newcastle |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse(s) | Hester Grenville (m. 1754) |

| Children | 5, including William Pitt the Younger |

| Parents | Robert Pitt Harriet Villiers |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

Net worth

history, was a prominent statesman and politician who served as British Prime Minister from 1766 to 1768. Despite his extensive career in government, Pitt's net worth is estimated to be between $100,000 and $1 million in 2024. This can be attributed to the fact that wealth accumulation during his time in office was not as substantial as it is today. Nevertheless, Pitt's legacy lies not in his monetary worth, but in his significant contributions to British politics and his role in shaping the nation's history.

Famous Quotes:

When trade is at stake, it is your last entrenchment; you must defend it, or perish...Sir, Spain knows the consequence of a war in America; whoever gains, it must prove fatal to her...is this any longer a nation? Is this any longer an English Parliament, if with more ships in your harbours than in all the navies of Europe; with above two millions of people in your American colonies, you will bear to hear of the expediency of receiving from Spain an insecure, unsatisfactory, dishonourable Convention?

Biography/Timeline

Pitt was the grandson of Thomas Pitt (1653–1726), the governor of Madras, known as "Diamond" Pitt for having discovered and sold a Diamond of extraordinary size to the Duke of Orléans for around £135,000. This transaction, as well as other trading deals in India, established the Pitt family fortune. After returning home the Governor was able to raise his family to a position of wealth and political influence: in 1691 he purchased the property of Boconnoc in Cornwall, which gave him control of a seat in Parliament. He made further land purchases and became one of the dominant political figures in the West Country controlling seats such as the rotten borough of Old Sarum.

William's father was Robert Pitt (1680–1727), the eldest son of Governor Pitt, who served as a Tory Member of Parliament from 1705 to 1727. His mother was Harriet Villiers, the daughter of Edward Villiers-FitzGerald and the Irish heiress Katherine FitzGerald. Both William's paternal uncles Thomas and John were MPs, while his aunt Lucy married the leading Whig Politician and soldier General James Stanhope. From 1717 to 1721 Stanhope served as effective First Minister in the Stanhope–Sunderland Ministry and was a useful political contact for the Pitt family until the collapse of the South Sea Bubble, a disaster which engulfed the government.

William Pitt was born at Golden Square, Westminster, on 15 November 1708. His older brother Thomas Pitt had been born in 1704. There were also five sisters: Harriet, Catherine, Ann, Elizabeth, and Mary. From 1719 william was educated at Eton College along with his brother. william disliked Eton, later claiming that "a public school might suit a boy of turbulent disposition but would not do where there was any gentleness". It was at school that Pitt began to suffer from gout. In 1726 Governor Pitt died, and the family estate at Boconnoc passed to William's father. When he died the following year, Boconnoc was inherited by William's elder brother, Thomas Pitt of Boconnoc.

In January 1727, william was entered as a gentleman commoner at Trinity College, Oxford. There is evidence that he was an extensive reader, if not a minutely accurate classical scholar. Demosthenes was his favourite author. william diligently cultivated the faculty of expression by the practice of translation and re-translation. In these years he became a close friend of George Lyttelton, who would later become a leading Politician. In 1728 a violent attack of gout compelled him to leave Oxford University without finishing his degree. He then chose to travel abroad. He spent some time in France and Italy on the Grand Tour and from 1728 to 1730 he attended Utrecht University in the Dutch Republic. He had recovered from the attack of gout, but the disease proved intractable, and he continued to be subject to attacks of growing intensity at frequent intervals until his death.

In May of the same year Pitt was promoted to the more important and lucrative office of paymaster-general, which gave him a place in the privy council, though not in the cabinet. Here he had an opportunity of displaying his public spirit and integrity in a way that deeply impressed both the king and the country. It had been the usual practise of previous paymasters to appropriate to themselves the interest of all money lying in their hands by way of advance, and also to accept a commission of 1/2% on all foreign subsidies. Although there was no strong public sentiment against the practice, Pitt completely refused to profit by it. All advances were lodged by him in the Bank of England until required, and all subsidies were paid over without deduction, even though it was pressed upon him, so that he did not draw a shilling from his office beyond the salary legally attaching to it. Pitt ostentatiously made this clear to everyone, although he was in fact following what Henry Pelham had done when he had held the post between 1730 and 1743. This helped to establish Pitt's reputation with the British people for honesty and placing the interests of the nation before his own.

Pitt soon joined a faction of discontented Whigs known as the Patriots who formed part of the opposition. The group commonly met at Stowe House, the country estate of Lord Cobham, who was a leader of the group. Cobham had originally been a supporter of the government under Sir Robert Walpole, but a dispute over the controversial Excise Bill of 1733 had seen them join the opposition. Pitt swiftly became one of the faction's most prominent members.

Pitt's military career was destined to be relatively short. His older brother Thomas was returned at the general election of 1734 for two separate seats, Okehampton and Old Sarum, and chose to sit for Okehampton, passing the vacant seat to william. Accordingly, in February 1735, william Pitt entered parliament as member for Old Sarum. He became one of a large number of serving army officers in the House of Commons.

He became such a troublesome critic of the government that Walpole moved to punish him by arranging his dismissal from the army in 1736, along with several of his friends and political allies. This provoked a wave of hostility to Walpole because many saw such an act as unconstitutional — that members of Parliament were being dismissed for their freedom of speech in attacking the government, something protected by Parliamentary privilege. None of the men had their commissions reinstated, however, and the incident brought an end to Pitt's military career. The loss of Pitt's commission was soon compensated. The heir to the throne, Frederick, Prince of Wales was involved in a long-running dispute with his father, George II, and was the patron of the opposition. He appointed Pitt one of his Grooms of the Bedchamber as a reward.

Owing to public pressure, the British government was pushed towards declaring war with Spain in 1739. Britain began with a success at Porto Bello. However the war effort soon stalled, and Pitt alleged that the government was not prosecuting the war effectively—demonstrated by the fact that the British waited two years before taking further offensive action fearing that further British victories would provoke the French into declaring war. When they did so, a failed attack was made on the South American port of Cartagena which left thousands of British troops dead, over half from disease, and cost many ships. The decision to attack during the rainy season was held as further evidence of the government's incompetence.

Walpole and Newcastle were now giving the war in Europe, which had recently broken out, a much higher priority than the colonial conflict with Spain in the Americas. Prussia and Austria went to war in 1740, with many other European states soon joining in. There was a fear that France would launch an invasion of Hanover, which was linked to Britain through the crown of George II. To avert this Walpole and Newcastle decided to pay a large subsidy to both Austria and to Hanover, in order for them to raise troops and defend themselves.

Many of Pitt's attacks on the government were directed personally at Sir Robert Walpole who had now been Prime Minister for twenty years. He spoke in favour of the motion in 1742 for an inquiry into the last ten years of Walpole's administration. In February 1742, following poor election results and the disaster at Cartagena, Walpole was at last forced to succumb to the long-continued attacks of opposition, resigned and took a peerage.

The administration formed by the Pelhams in 1744, after the dismissal of Carteret, included many of Pitt's former Patriot allies, but Pitt was not granted a position because of continued ill-feeling by the King and leading Whigs about his views on Hanover. In 1744 Pitt received a large boost to his personal fortune when the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough died leaving him a legacy of £10,000 as an "acknowledgment of the noble defence he had made for the support of the laws of England and to prevent the ruin of his country". It was probably as much a mark of her dislike of Walpole as of her admiration of Pitt.

Pitt now expected a new government to be formed led by Pulteney and dominated by Tories and Patriot Whigs in which he could expect a junior position. Walpole was instead succeeded as Prime Minister by Lord Wilmington, though the real power in the new government was divided between Lord Carteret and the Pelham brothers (Henry and Thomas, Duke of Newcastle). Walpole had carefully orchestrated this new government as a continuance of his own, and continued to advise it up to his death in 1745. Pitt's hopes for a place in the government were thwarted, and he remained in opposition. He was therefore unable to make any personal gain from the downfall of Walpole, to which he had personally contributed a great deal.

Between 1746 and 1748 Pitt worked closely with Newcastle in formulating British military and diplomatic strategy. He shared with Newcastle a belief that Britain should continue to fight until it could receive generous peace terms – in contrast to some such as Henry Pelham who favoured an immediate peace. Pitt was personally saddened when his friend and brother-in-law Thomas Grenville was killed at the naval First Battle of Cape Finisterre in 1747. However, this victory helped secure British supremacy of the sea which gave the British a stronger negotiating position when it came to the peace talks that ended the war. At the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748 British colonial conquests were exchanged for a French withdrawal from Brussels. Many saw this as merely an armistice and awaited an imminent new war.

Despite his disappointment there was no immediate open breach. Pitt continued at his post; and at the general election which took place during the year he even accepted a nomination for the Duke's pocket borough of Aldborough. He had sat for Seaford since 1747. The government won a landslide, further strengthening its majority in parliament.

However, there were strong reasons for concluding the peace: the National Debt had increased from £74.5m. in 1755 to £133.25m. in 1763, the year of the peace. The requirement to pay down this debt, and the lack of French threat in Canada, were major movers in the subsequent American War of Independence.

In December 1756, Pitt, who now sat for Okehampton, became Secretary of State for the Southern Department, and Leader of the House of Commons under the premiership of the Duke of Devonshire. Upon entering this coalition, Pitt said to Devonshire: "My Lord, I am sure I can save this country, and no one else can".

Pitt's particular genius was to Finance an army on the continent to drain French men and resources so that Britain might concentrate on what he held to be the vital spheres: Canada and the West Indies; whilst Clive successfully defeated Siraj Ud Daulah, (the last independent Nawab of Bengal) at Plassey (1757), securing India. The Continental campaign was carried on by Cumberland, defeated at Hastenbeck and forced to surrender at Convention of Klosterzeven (1757) and thereafter by Ferdinand of Brunswick, later Victor at Minden; Britain's Continental campaign had two major strands, firstly subsidising allies, particularly Frederick the Great, and second, financing an army to divert French resources from the colonial war and to also defend Hanover (which was the territory of the Kings of England at this time)

In Europe, Brunswick's forces enjoyed a mixed year. Brunswick had crossed the Rhine, but faced with being cut off he had retreated and blocked any potential French move towards Hanover with his victory at the Battle of Krefeld. The year ended with something approaching a stalemate in Germany. Pitt had continued his naval descents during 1758, but the first had enjoyed only limited success and the second ended with near disaster at the Battle of St Cast and no further descents were planned. Instead the troops and ships would be used as part of the coming expedition to the French West Indies. The scheme of amphibious raids was the only one of Pitt's policies during the war that was broadly a failure, although it did help briefly relieve pressure on the German front by trying down French troops on coastal protection Service.

In France a new leader, the Duc de Choiseul, had recently come to power and 1759 offered a duel between their rival strategies. Pitt intended to continue with his plan of tying down French forces in Germany while continuing the assault on France's colonies. Choiseul hoped to repel the attacks in the colonies while seeking total victory in Europe.

George II died on 25 October 1760, and was succeeded by his grandson, George III. The new king was inclined to view politics in personal terms and taught to believe that 'Pitt had the blackest of hearts'. The new king had counsellors of his own, led by Lord Bute. Bute soon joined the cabinet as a Northern Secretary and Pitt and he were quickly in dispute over a number of issues.

After his resignation in October 1761, the King urged Pitt to accept a mark of royal favour. Accordingly, he obtained a pension of £3000 a year and his wife, Lady Hester Grenville was created Baroness Chatham in her own right—although Pitt refused to accept a title himself. Pitt assured the King that he would not go into direct opposition against the government. His conduct after his retirement was distinguished by a moderation and disinterestedness which, as Burke has remarked, "set a seal upon his character." The war with Spain, in which he had urged the cabinet to take the initiative, proved inevitable; but he scorned to use the occasion for "altercation and recrimination", and spoke in support of the government measures for carrying on the war.

In 1761 Pitt had received information from his agents about a secret Bourbon Family Compact by which the Bourbons of France and Spain bound themselves in an offensive alliance against Britain. Spain was concerned that Britain's victories over France had left them too powerful, and were a threat in the long term to Spain's own empire. Equally they may have believed that the British had become overstretched by fighting a global war and decided to try to seize British possessions such as Jamaica. A secret convention pledged that if Britain and France were still at war by 1 May 1762, Spain would enter the war on the French side.

Pitt had not been long out of office when he was solicited to return to it, and the solicitations were more than once renewed. Unsuccessful overtures were made to him in 1763, and twice in 1765, in May and June—the negotiator in May being the king's uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, who went down in person to Hayes, Pitt's seat in Kent. It is known that he had the opportunity of joining the Marquess of Rockingham's short-lived administration at any time on his own terms, and his conduct in declining an arrangement with that minister has been more generally condemned than any other step in his public life.

During 1765 he seems to have been totally incapacitated for public Business. In the following year he supported with great power the proposal of the Rockingham administration for the repeal of the American Stamp Act, arguing that it was unconstitutional to impose taxes upon the colonies. He thus endorsed the contention of the colonists on the ground of principle, while the majority of those who acted with him contented themselves with resisting the disastrous taxation scheme on the ground of expediency.

The present problems which faced the government included the observance of the Treaty of Paris by France and Spain, tension between American colonists and the mother country, and the status of the East India Company. Chatham set about his duties with tempestuous Energy. One of the new ministry's earliest acts was to lay an embargo upon corn, which was thought necessary in order to prevent a dearth resulting from the unprecedented bad harvest of 1766. The measure was strongly opposed, and Lord Chatham delivered his first speech in the House of Lords in support of it. It proved to be almost the only measure introduced by his government in which he personally interested himself.

In 1767, Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, enacted duties in the American colonies on tea, paper, and other goods. The taxes were created without the consultation of Chatham and possibly against his wishes. They proved offensive to the American colonists. Chatham's attention had been directed to the growing importance of the affairs of India, and there is evidence in his correspondence that he was meditating a comprehensive scheme for transferring much of the power of the East India Company to the crown. Yet he was incapacitated physically and mentally during nearly his entire tenure of office. Chatham rarely saw any of his colleagues though they repeatedly and urgently pressed for interviews with him, and even an offer from the King to visit him in person was respectfully declined. While his gout seemed to improve, he was newly afflicted with mental alienation bordering on insanity. Chatham's lack of leadership resulted in an incohesive set of policies.

Chatham dismissed his allies Amherst and Shelburne from their posts, and then in October 1768 he tendered his own resignation on the grounds of poor health, leaving the leadership to Grafton, his First Lord of the Treasury.

Soon after his resignation a renewed attack of gout freed Chatham from the mental disease under which he had so long suffered. He had been nearly two years and a half in seclusion when, in July 1769, he again appeared in public at a royal levee. It was not, however, until 1770 that he resumed his seat in the House of Lords.

Chatham sought to find a compromise on the escalating conflict with the American colonies. As he realised the gravity of the American situation, Chatham re-entered the fray, declaring that 'he would be in earnest for the public' and 'a scarecrow of violence to the gentler warblers of the grove'. His position changed from an obsession in 1774 with the question of the authority of Parliament to a search for a formula for conciliation in 1775. He proposed the "Provisional Act" that would both maintain the ultimate authority of Parliamentary sovereignty, while meeting the colonial demands. The Lords defeated his proposal on 1 February 1775. Chatham's warnings regarding America were ignored. His brave efforts to present his case, passionate, deeply pondered, for the concession of fundamental liberties—no taxation without consent, independent judges, trial by jury, along with the recognition of the American Continental Congress—foundered on the arrogance and complacency of his peers.

He was removed to his seat at Hayes, where his middle son william read to him Homer's passage about the death of Hector. Chatham died on 11 May 1778, aged 69. Although he was initially buried at Hayes, with graceful unanimity all parties combined to show their sense of the national loss and the Commons presented an address to the king praying that the deceased statesman might be buried with the honours of a public funeral. A sum was voted for a public monument which was erected over a new grave in Westminster Abbey. In the Guildhall Edmund Burke's inscription summed up what he had meant to the City: he was 'the minister by whom commerce was united with and made to flourish by war'. Soon after the funeral a bill was passed bestowing a pension of £4,000 a year on his successors in the earldom. He had a family of three sons and two daughters, of whom the second son, william, was destined to add fresh lustre to a name which is one of the greatest in the history of England.

It has been suggested that Pitt was in fact a far more orthodox Whig than has been historically portrayed demonstrated by his sitting for rotten borough seats controlled by arisocratic magnates, and his lifelong concern for protecting the balance of power on the European continent – which marked him out from many other Patriots.

The same year when Britain and Spain became involved in the Falklands Crisis and came close to war, Pitt was a staunch advocate of taking a tough stance with Madrid and Paris (as he had been during the earlier Corsican Crisis when France had invaded Corsica) and made a number of speeches on the subject rousing public opinion. The government of Lord North was pushed into taking a firmer line because of this, mobilising the navy, and forcing Spain to back down. Some had even believed that the issue was enough to cast North from office and restore Pitt as Prime Minister—although the ultimate result was to strengthen the position of North who took credit for his firm handling of the crisis and was able to fill the cabinet with his own supporters. North would go on to dominate politics for the next decade, leading the country until 1782.